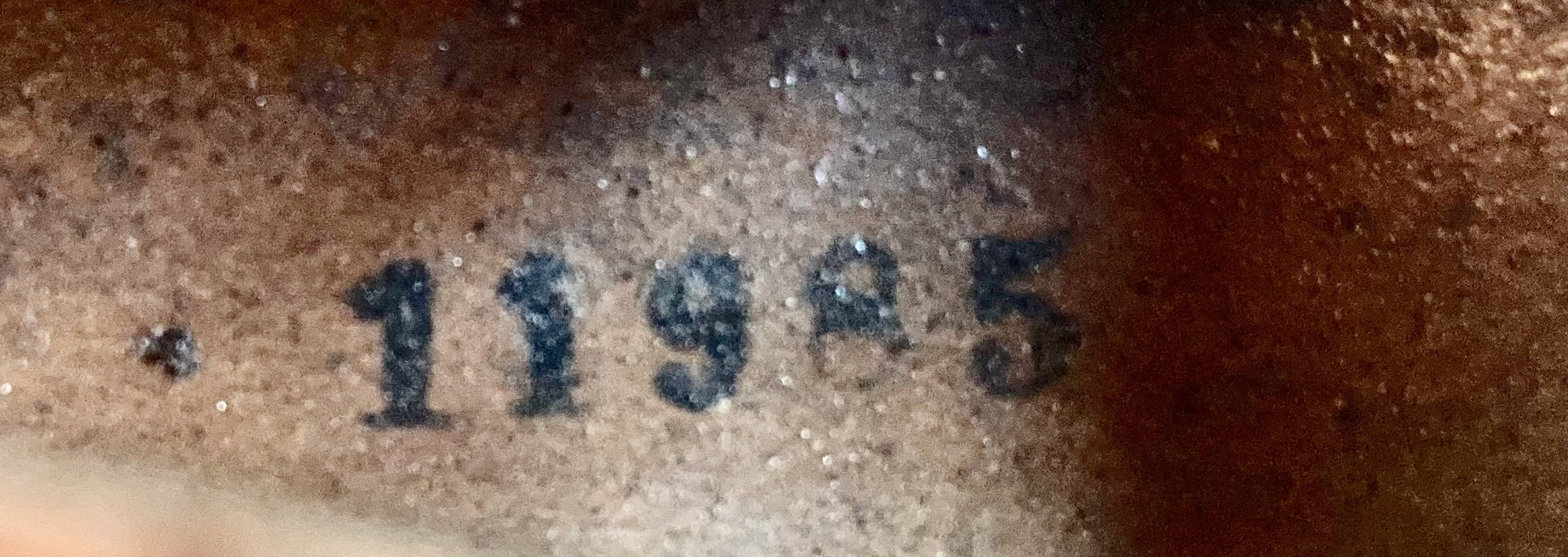

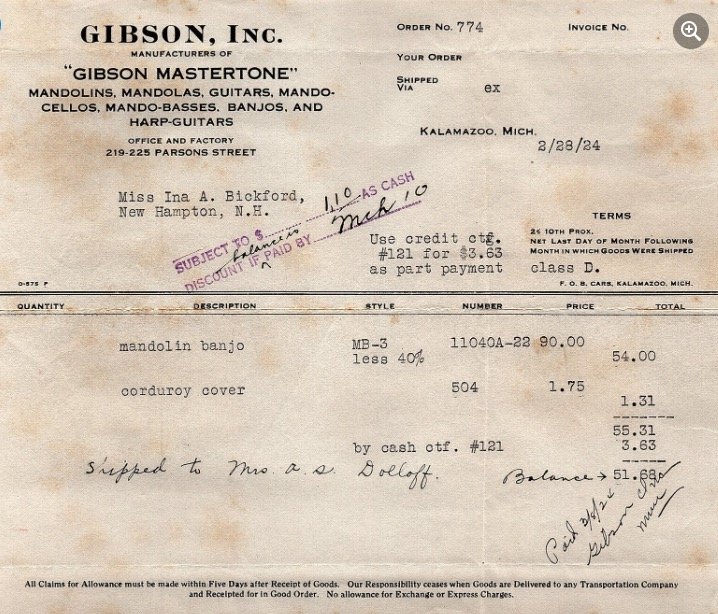

On Monday, December 1, 1924, Lloyd Loar made his final mark on the legacy of the F-5 mandolin. The mandolins and guitars bearing that date are the last known Master Model Gibson instruments to carry that iconic and highly sought signature, "Lloyd Loar." At Gibson, groups of instruments, called batches, were usually stamped with a number to help carry instruments of similar specifications throughout the production process. Once completed, the signature and dates were written on a paper label and placed over the stamp number. Consequently, stamp numbers from signed Loars are rarely known. However, one such label on a December 1, 1924 F-5 peeled off revealing stamp number 11985. Since the stamp numbers were in numerical order, it appears that that batch was among the last instruments stamped in 1923 (In 1924, a new numerical series was started, all with the suffix "A"). From the scant evidence we currently have, we observe that no F-5 mandolins were stamped in 1924. (There may be evidence that at least one H-5 mandola, 11058A, was stamped in early 1924). Our conclusion is that there was an effort to push the Master Model project on through production while Loar was still on hand. According to a press release, Mr. Loar was scheduled to "leave (Kalamazoo) early in December." (See Episode 7: The Beginning Of The End.")

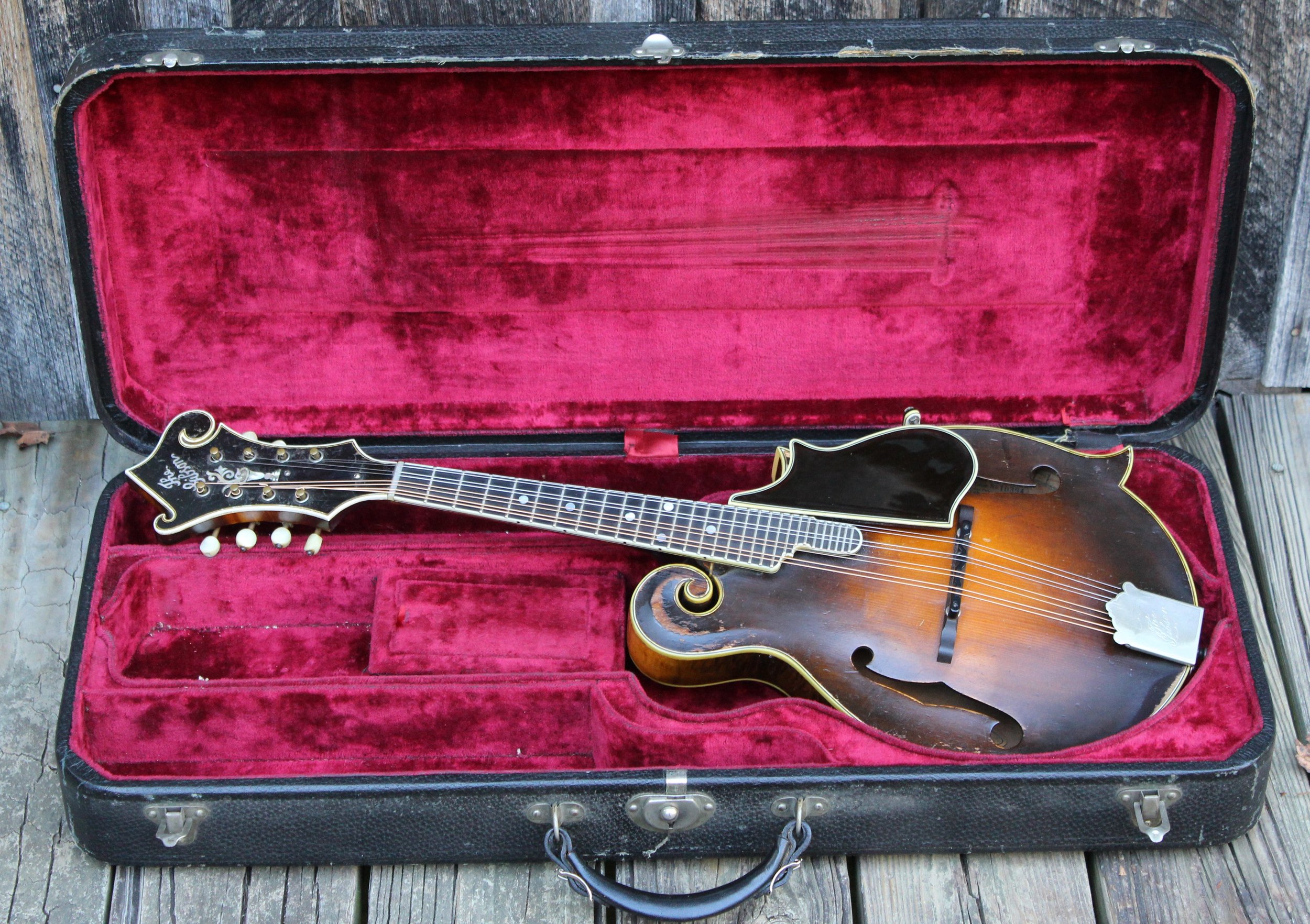

Gibson F-5 79641, signed “Lloyd Loar” December 1, 1924.

Like all the mandolins we have seen from the December 1 batch, Gibson F-5 # 79641 (shown above), has the powerful dark sound which has much in common with the celebrated F-5s from February 18 and March 31 of earlier that year. To match the dark sound, they have a rich, lustrous dark sunburst varnish finish. Features and appointments are also consistent with standard specifications including the carved Adirondack spruce top; parallel tone bars; f-holes and bridge centered in top; quarter-sawn sugar maple book-matched back; one-piece slab-cut sugar maple neck; headstock inlay consisting of “The Gibson” in mother-of-pearl and abalone flowerpot; Waverly pearl button tuners with notched endplate; hand-engraved tailpiece; pickguard following body points; silver plated hardware; red-lined Geib and Schaefer case. (More photos, info and video at F-5 79641)

Gibson F-5 79641, signed “Lloyd Loar” December 1, 1924, in original Geib and Schaefer case.

For whatever reason, a few F-5s from the 11985 batch did not receive the signature label. Today they are often referred to as the "unsigned Loars" because they closely resemble their signed batch mates in almost every respect except gold hardware, the signature label, and a few have nitrocellulose overspray. The serial number of these mandolins place them in a sequence of 1925; therefore, we might conclude that the last steps of production took place after Loar had already left Gibson.

Gibson F-5 #80783, one of a few rare instruments commonly referred to as an “unsigned Loar.” Photos courtesy Ken Walthan.

Gibson F-5 #80783. Photos courtesy Ken Walthan.

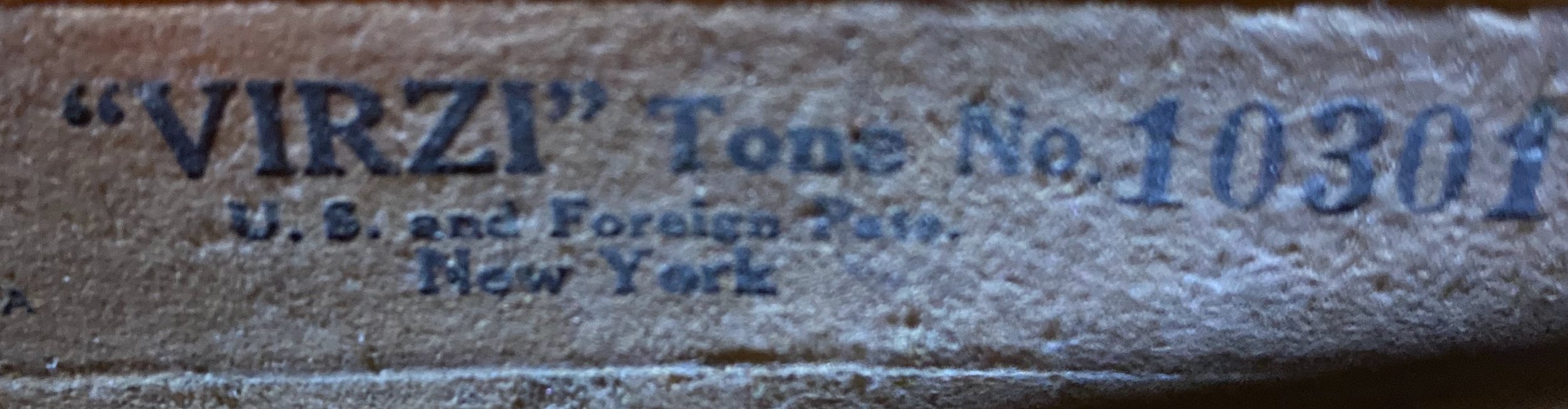

The most striking thing about Gibson F-5 80783 (unsigned Loar) is its dark, richly nuanced tone that blends silky texture with auditorium-filling projection. It has appointments almost identical to those from 79641 except for gold-plated hardware. Like many of the F-5s from 1924, it has the Virzi Tone Producer.

While the F-5s released in the months after December of 1924 have the Master Model label, no signature label was applied, leaving the stamp number, 11985, visible under the f-hole where the label would have been placed.

Stamp number from F-5 81268, formerly owned by the late Butch Baldassari. The first F-5s released in 1925 after Lloyd Loar’s departure all share the same stamp number as found on F-5s signed December 1, 1924.

Another extraordinary example of an F-5 with the December 1st signature label is Gibson F-5 79719.

Gibson F-5 79719 signed December 1, 1924. Gold plated tuners and pickguard consistent with 1930s specification.

Gibson F-5 79719 is a prime example of the lustrous dark tone consistent with this batch. Below, hear a studio recording by Tony Williamson playing his arrangements of “Theme and Twin Rivers Rag” on this great F-5. (Recorded by Jerry Brown of the Rubber Room in Chapel Hill, NC., through a pair of vintage Neumann u47 microphones, with with no reverb or effects).

Clearly, all the mandolins from the 11985 batch share many common features, with impressive sound, striking wood and gorgeous finish. However, there are differences as well. In the photo below, we can see minor variations in the logo and inlay. More strikingly, notice the difference in the tuners. Gibson F-5 79719 (in middle) features gold plated F-5 tuners that weren’t standard factory specification until the 1930s. The tuner buttons are grained ivoroid instead of pearl, but more importantly, the tuner posts of 79719 require a different spacing in the peghead. There is no sign of the kind of alteration (plug and re-drill) from original that would have been required for a retro-fit. How is this possible?

Pegheads, L to R: 79641, 79719 and 80783; notice variations in logo, inlay and tuners. (photo of 80783 courtesy Ken Waltham)

Lloyd Loar had connected with Albert D. Grover at the Guild convention in Pittsburgh back in April and even shared his musical saw with Mr. Grover’s son, Walter, on stage during the final performance. The elder Grover was a fascinating and eccentric character; we imagine the two inventors having conversations late through the evening about a variety of musical innovations. As an offshoot, Loar negotiated a deal for Gibson to use the “Grover Internal Gear peg” on banjos (see below). In all likelihood, the need for an improved mandolin tuner was also discussed, and by December 1924 the prototype for the new design had arrived and was “tried and tested” on F-5 79719. (To match, a gold-plated tailpiece was installed, but at present the gold has worn off the cover, showing nickel underneath).

Left: Back of peghead of F5 79719 with the prototype Grover tuner; right: back of peghead on 79641 with the standard Waverly tuner. Notice the cog (round gear) of the Grover tuner is below the worm gear. When the button turns the shaft of the worm gear, the cog turns the string post to tighten or loosen the string. The issue with the Waverly tuner was that the string tension tended to pull the gears away from each other,; by reversing the position of the gears, turning the post tended to pull the gears together.

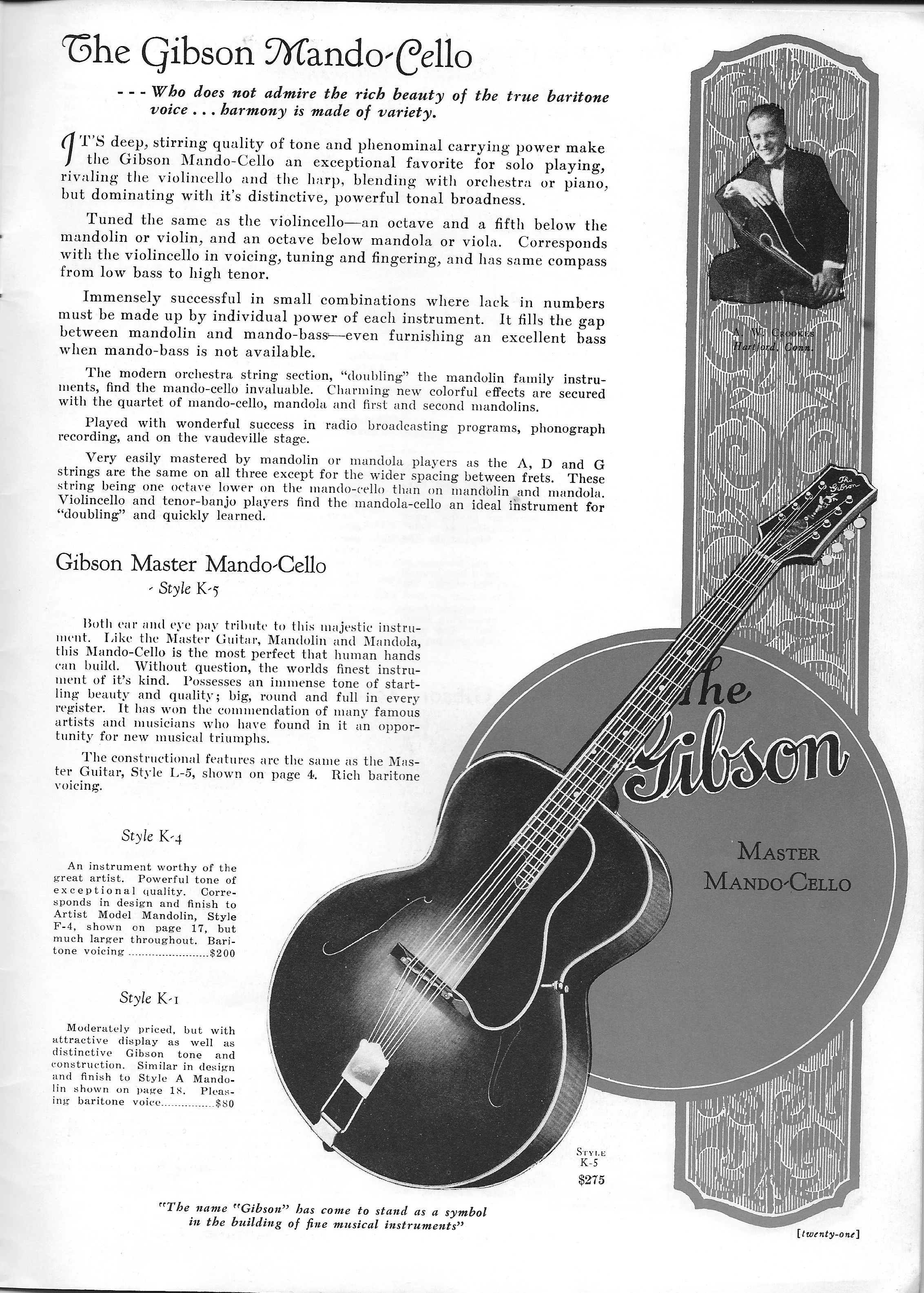

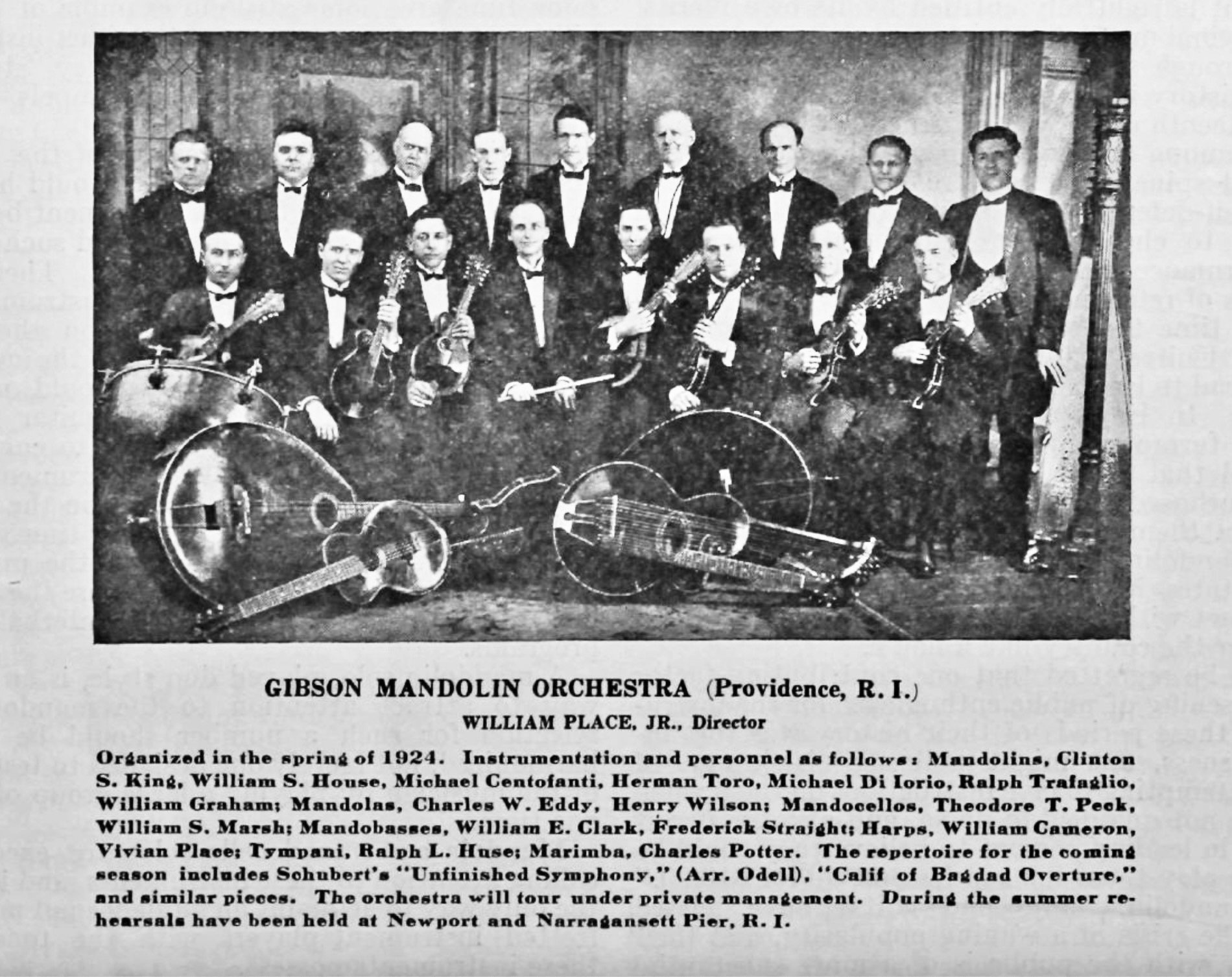

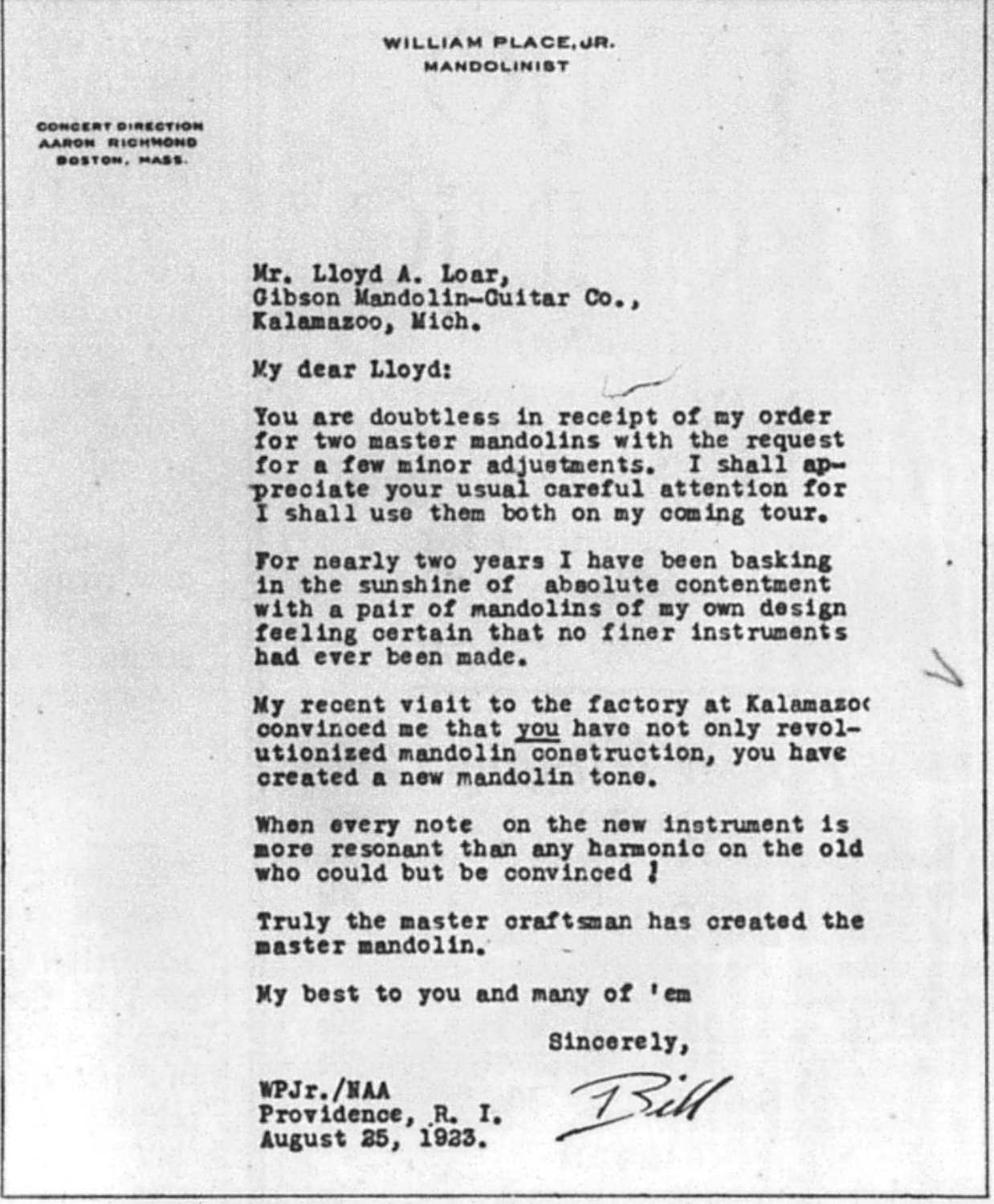

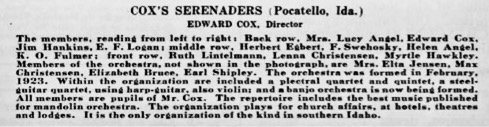

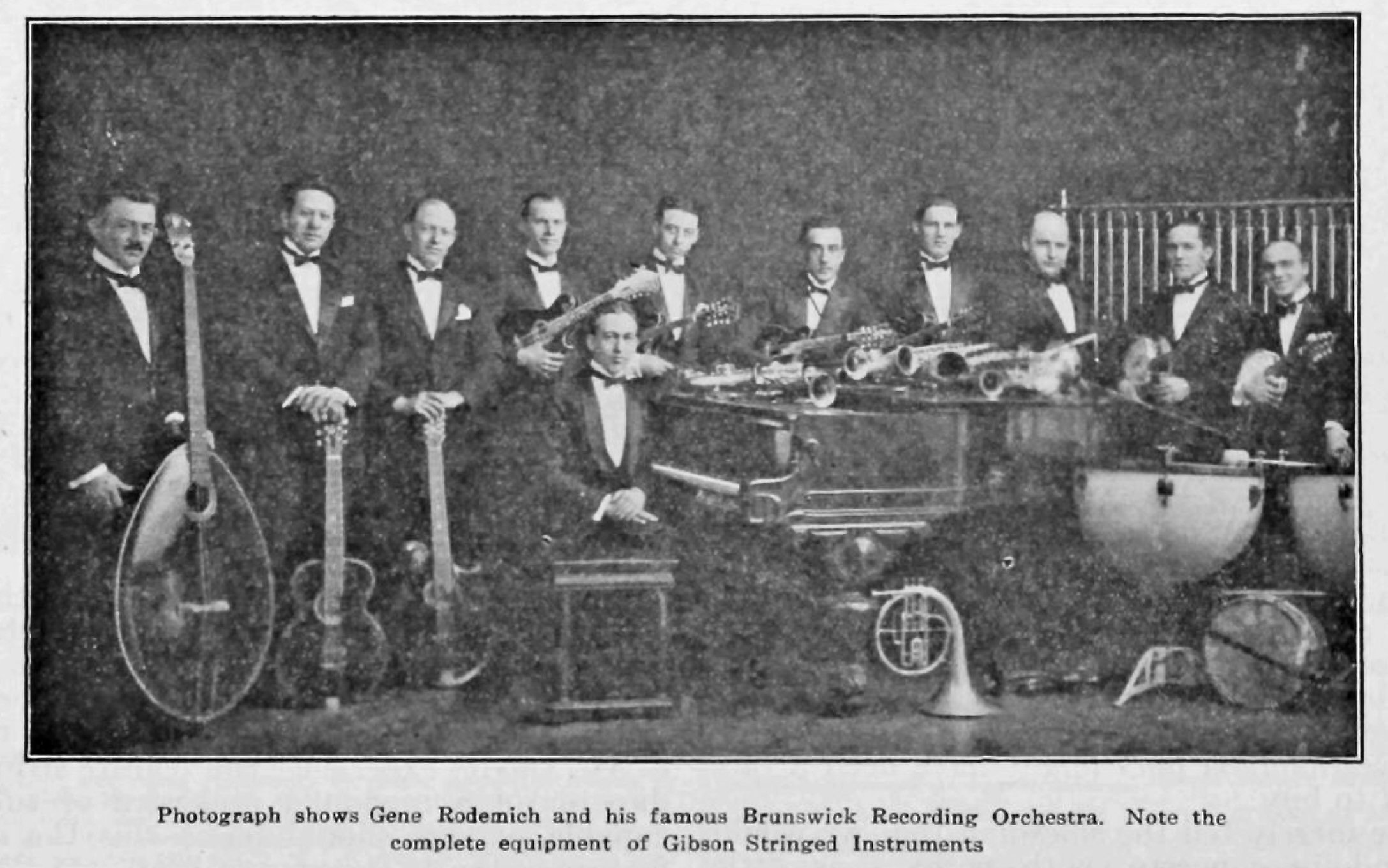

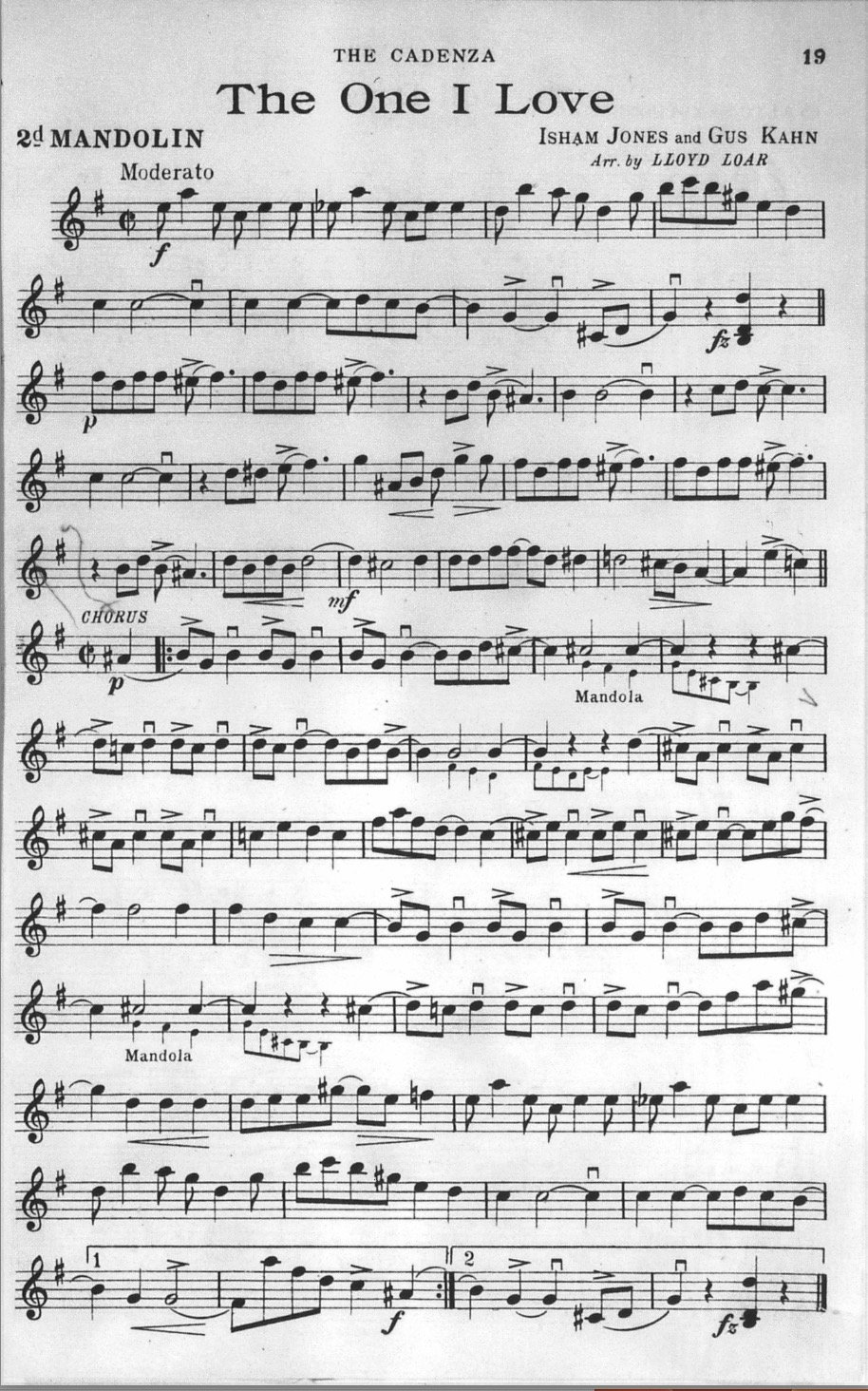

Whille Gibson was set to phase out the F-5 in pursuit of more profitable enterprises, many Master Model Mandolins, and a few Mandolas and Mandocellos were already in use. Soloists like Dave Apollon and Vincent Paladino were blistering out obligatos in Vaudeville with their F-5s; dance bands like The Kansas City Nighthawks, Gene Rodemich’s, Isham Jones’ and Paul Whiteman’s Orchestras all carried plectrum sections featuring Loar instruments. The F-5 was front and center and the H-5 and K-5 in support in mandolin orchestras across the country, including those led by Walter Kaye Bauer and W. A. Crookes in Hartford, Connecticut; William Place in Providence, Rhode Island; Conrad Gebelein in Baltimore, Maryland; Albert Belson in Minneapolis, Minnesota; Herman Von Bernewitz in Washington DC; Claud Doerr in Chicago, Illinois; B. D. Conklin in Decatur, Illinois; Edward Cox in Pocatello, Idaho; Melvin Deets in Hershey, Pennsylvania; D. E. Hartnett in New York City; MacGregor Sorley in Toronto, Canada; T. A. Miles in Knoxville, Tennessee; Marguerite Lavery in Detroit, Michigan; R. W. Williams in Salisbury, North Carolina; Percy Lichtenfels in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Joseph Rybka in Portland, Oregon; William Griffith in Atlanta, Georgia; and Robert L. Sharp in Memphis, Tennessee.

The cover of the December issue of the Cadenza featured the Memphis Plectrum Orchestra. Leader Robert L. Sharpe (front row, on right) and two others had F-5 mandolins by August, 1924. Jacobs Orchestra Monthly and The Cadenza, December, 1924, p. 64.

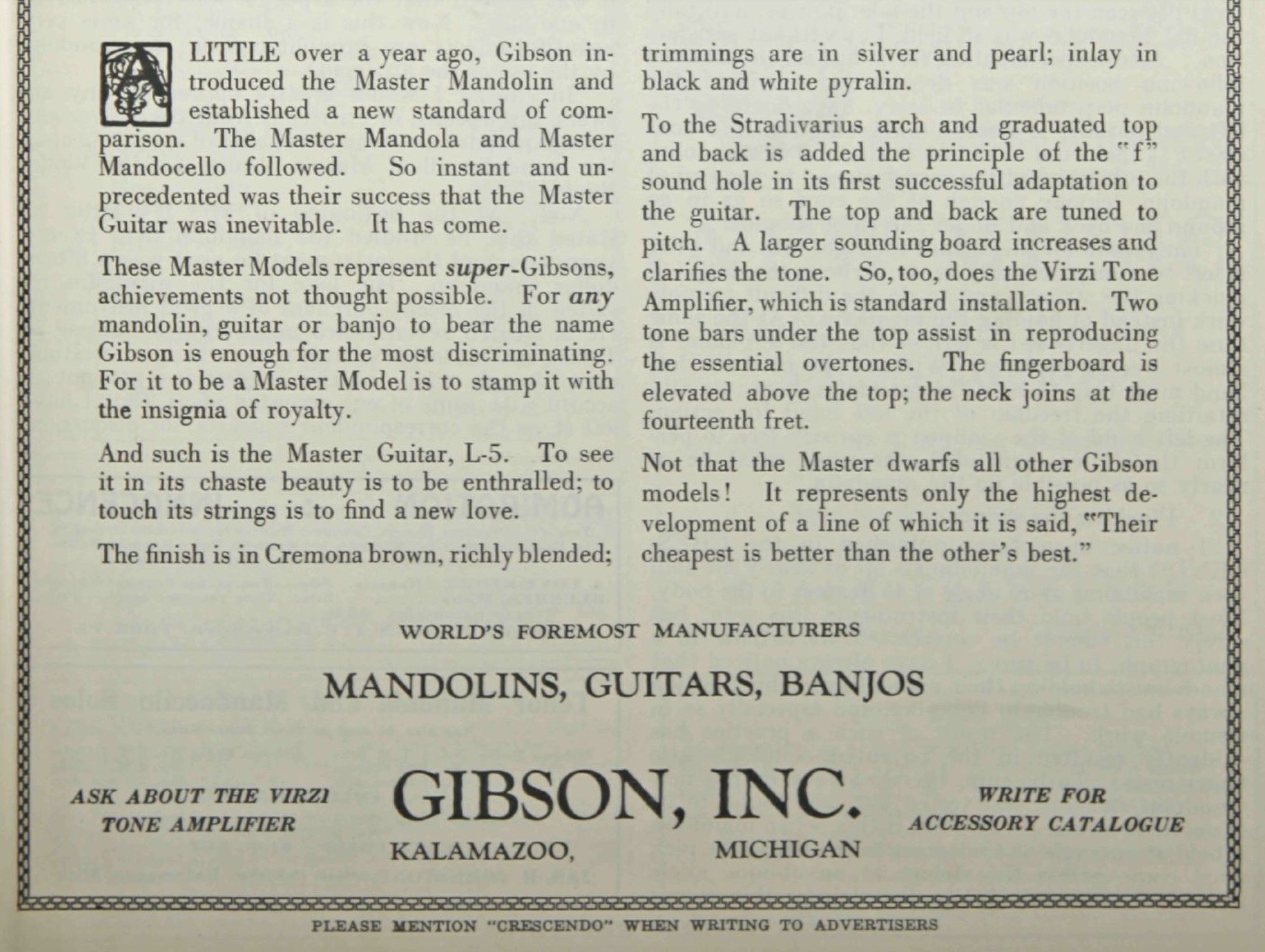

The Loar-signed instruments maintained a great deal of consistency over the two-year span in production, but by December the F-5 seemed almost anachronistic considering the sweeping changes being implemented in other areas of Gibson production. Even the name of the company had been changed by former General Manager Harry Ferris to “Gibson, Inc.,” to move away from “out of date instruments like mandolin.” Yet the Master Model label continued to maintain the original name, “The Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Company,” throughout the 1920s.

Master Model label from F-5 84682 from the late 1920s.

In 1923, when he took the helm at Gibson, Harry Ferris called for a reduction in number of models produced. By 1925, not only was the Master Model almost in danger of elimination, many other mandolin models were discontinued or phased out: A-Jr., A-2 & A-2Z (by 1927), A3 mandolins; H-2 mandola; K-2 mandocello; TL-1 tenor lute; Style J Mandobass (by 1930); Style O and L-1 guitars (round sound hole archtops).

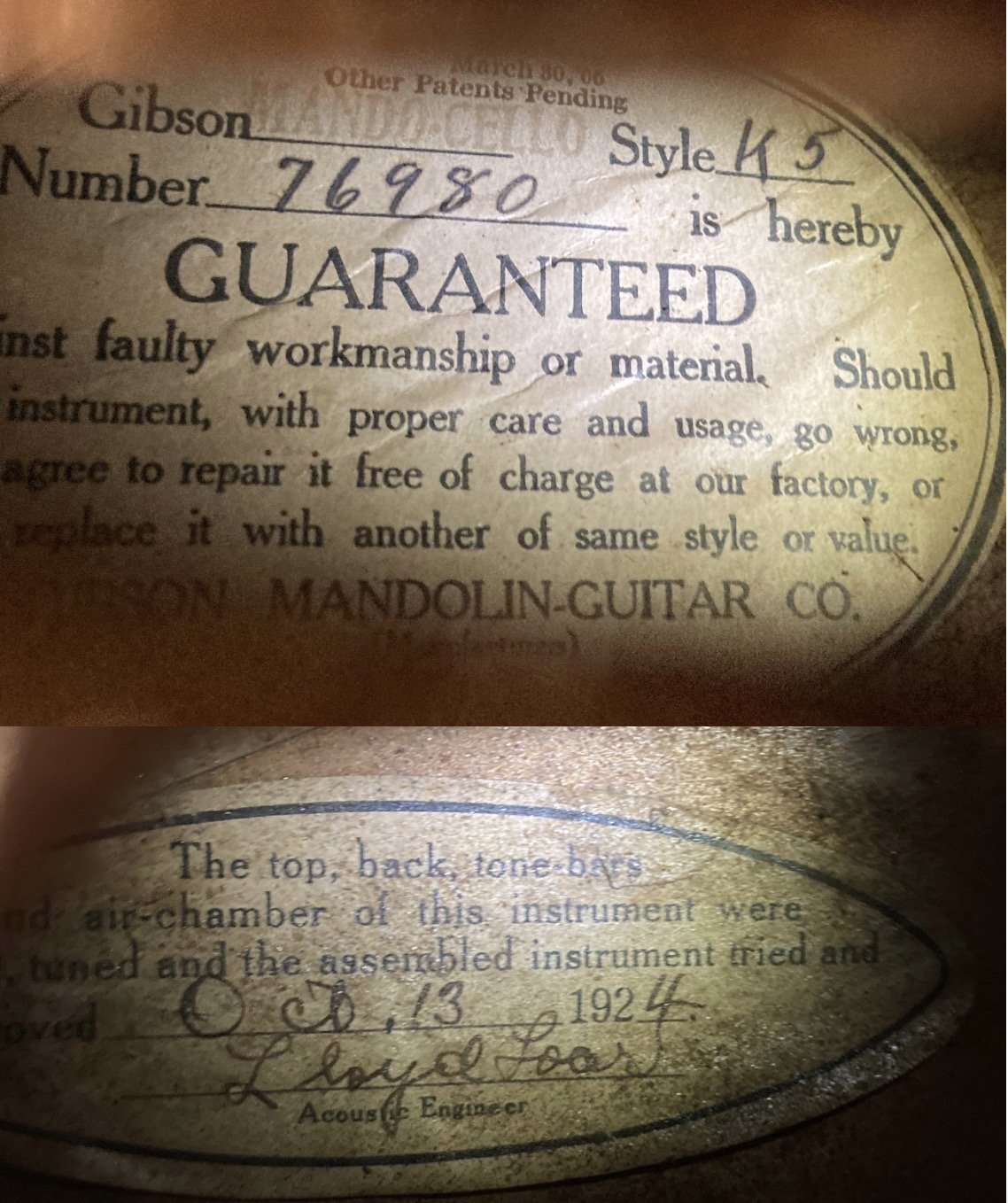

We have found no record of any batches of F-5 mandolins built in 1924 and 1925; there is evidence that many of those built in 1924 remained unsold. The F-5 returned into production in 1926 with slightly different specifications. Although the H-5 mandola and K-5 mandocello did not disappear from the Gibson catalogs until 1935, production was very limited, with only a few produced after 1924.

Another mandate instituted by GM Harry Ferris and continued by his successor, Guy Hart, called for the “dismissal of unnecessary personnel.” The following employees were among those who were no longer at Gibson in 1925. (Their country of origin is noted if they were immigrants, and their job description as listed in the Kalamazoo City Directory. For more information on these workers, see “Breaking News 1922”).

Lloyd Loar, acoustic engineer

John S. Patterson, Swiss, wood carver

John J. Voisine, Canadian, woodworker

Adrian Glerum, Holland, wood worker (was rehired to carve violins in late 1930s)

Clyde E. Seward, woodworker

Henry T. Reeves, draftsman

Hans Dorthaus Larsen, Danish, cabinet maker

Fred Miller, finisher

Cornelius Kievit, Sr. finisher

Were these the builders of the F-5? Were they “unnecessary workers” dismissed because there was no longer a need for the Master Model project?

Unlike many of these workers, Lloyd Loar’s future endeavors were already set as he readied his pen for duty in the service of Walter Jacobs’ publishing enterprises in Boston. In his December installment in his series “Acoustics For the Musician” in the Jacobs Orchestra Monthy and the Cadenza, he offers useful insight on determining scale length and string gauge.

Jacobs Orchestra Monthly And The Cadenza, December, 1924.

In one of his last gifts to Gibson, Loar had negotiated a deal with A. D. Grover who publicly announced the “Grover Internal Gear Peg” and included a testimony by Loar. High-end Gibson banjos, guitars and mandolins would all use Grover tuners by the 1930s.

Jacobs Orchestra Monthly And The Cadenza, November, 1924.

Music Trades, August 2, 1924 p.24

While wrapping up his duties at Gibson, Loar still found time to perform at local events in Kalamazoo in October and November; for example, the following articles describe two charity drive concerts for the Presbyterian Church where he played duets with violinist Esther Rasmussen.

On left: Kalamazoo Gazette, October 26, 1924, p. 34; Right: Kalamazoo Gazette November 11, 1924, p. 14

We now return to the question: where was Loar in December, 1924? For answers, we once again look to the whereabouts of his wife, Mrs. Fisher Shipp-Loar, whose movements are chronicled in the newspaper reports of Brookfield, Missouri. In most cases when Loar was in Kalamazoo working at Gibson, his wife and musical partner, Fisher Shipp-Loar, would stay with her mother, Mrs. A. D. Shipp, in Brookfield, Missouri. During those times she would perform as a soloist, though when Loar was with her they would perform together. During most of December, she made public appearances without her husband. For example, on the afternoon of the 11th she entertained a class from the Christian Church.

The Brookfield Argus and the Linn County Farmer, Brookfield, Missouri, Saturday, December 13, 1924, P. 4

Lloyd Loar had arrived in Brookfield to join his wife by Saturday, December 20th.

Linn County Budget-Gazette, Brookfield, Missouri, Saturday, Dec 20, 1924 · Page 1

Mr. and Mrs. Loar attended the First Christian Church of Brookfield, Missouri at 1416 N Main Street on Sunday the 21st and were scheduled to “provide special music” for the Christmas sermon.

Linn County Daily Budget (Brookfield, Missouri) · Sat, Dec 20, 1924

On Tuesday, December 23rd, the couple performed at two different events: At noon, they performed vocal and instrumental numbers at the Rotary Club luncheon.

Linn County Budget-Gazette, Brookfield, Missouri. Wednesday, December 24, 1924, P. 4

The Brookfield Argus and the Linn County Farmer, Brookfield, Missouri. Tuesday, Dec 23, 1924, P. 1

In the afternoon of the 23rd, they appeared at a house concert in Linneus; the program is well documented with familiar performances by Loar on his August Diehl viola d’alta, his Gibson MV-5 and his musical saw. The report points out that Mr. Loar is no longer a professional musician, an interesting notice of a significant turning point in Loar’s musical trajectory.

The Daily News Bulletin, Dec. 23, 1924.p. 1.

On Wednesday evening, the 24th, the elder Mrs. Shipp invited friends and family for a Christmas Eve dinner.

24 Linn County Budget-Gazette, Brookfield, Missouri, Saturday, Dec 27, 1924, P. 4

On Christmas Day, the elder Mrs. Shipp hosted a family reunion and Christmas dinner with her children and spouses. Lloyd Loar left for Kalamazoo after dinner, most likely to finalize preparations to move out of his house there.

The Bulletin, Linneus, Missouri, Thursday, Dec 25, 1924 P. 4

On Saturday, December 27, Fisher Shipp-Loar said goodbye to her mother and left Brookfield for Kalamazoo, Michigan, to join her husband. From there, the couple went on to Boston for a new life.

Linn County Daily Budget Saturday, December 27, 1924, P. 2

Sallie Fisher Shipp had honed her musical and acting skills at the Academy of Music in Boston, and upon her graduation in 1900, launched her professional career. Within a few years, she was the darling of the Chautauqua circuit and delighted audiences and garnered accolades for the next twenty years. By 1924, modern audiences found her performance outdated. A return to Boston and her Alma Mater must have held out a vision of opportunity, inspiration, and perhaps a return to the vigor of youth. In documenting the years Mr. and Mrs. Loar had spent together and apart, one suspects that their personal relationship was never as committed as their musical collaboration, especially during the time Loar devoted his attentions to his many duties at Gibson in Kalamazoo. In Boston, the “Fisher Shipp Concert Company” would perform once again, and perhaps, for her, with a renewed energy.

Live radio broadcast on WBZ, Springfield Massachusetts. The Boston Globe, Boston, Massachusetts, March 15, 1927. P. 25

At the very latest, by Friday, December 19, Lloyd Loar had wrapped up his duties at Gibson, Inc. A new Factory Manager had been appointed and the announcement made public on Monday, December 22. George Altermatt would steer Gibson through the important banjo years to come.

Music Trades, December 17, 1924.

After Lloyd Loar left Gibson, his name no longer appeared on any of their labels or catalogs. In our understanding, it was the date on those labels and not the signature that was inconvenient. It conflicted with the “factory refresh” program. An F-5, left unsold at a store for a few years, would be sent back to the factory, sprayed with lacquer and was offer for sale as a new instrument. The date implied otherwise, and on some Loar instruments the label was removed or replaced.

After the Great Depression and by the end of World War II, the name Lloyd Loar, like the mandolin boom itself, was virtually unknown. It took 20 years of performance and constant travel by Bill Monroe before the signature inside his mandolin became recognized as a sign of quality. As prices began to rise, so did a mythology about the man. A proliferation of misinformation that began in the 1970s continues to this day::

1) He was like Stradivarius, building mandolins by hand, tuning and testing each one before he signed his name

2) and more recently, the opposite: he had little, if anything, to do with the building of musical instruments

3) Gibson hired a violin maker to build the mandolins and make an authentic Cremona varnish

4) the mandolin should be called the Loar-Hart F-5 (!!!)

5) the F-5 was designed strictly for serious classical music

6) Loar left Gibson in October of 1924 and had nothing to do with the instruments made in November and December.

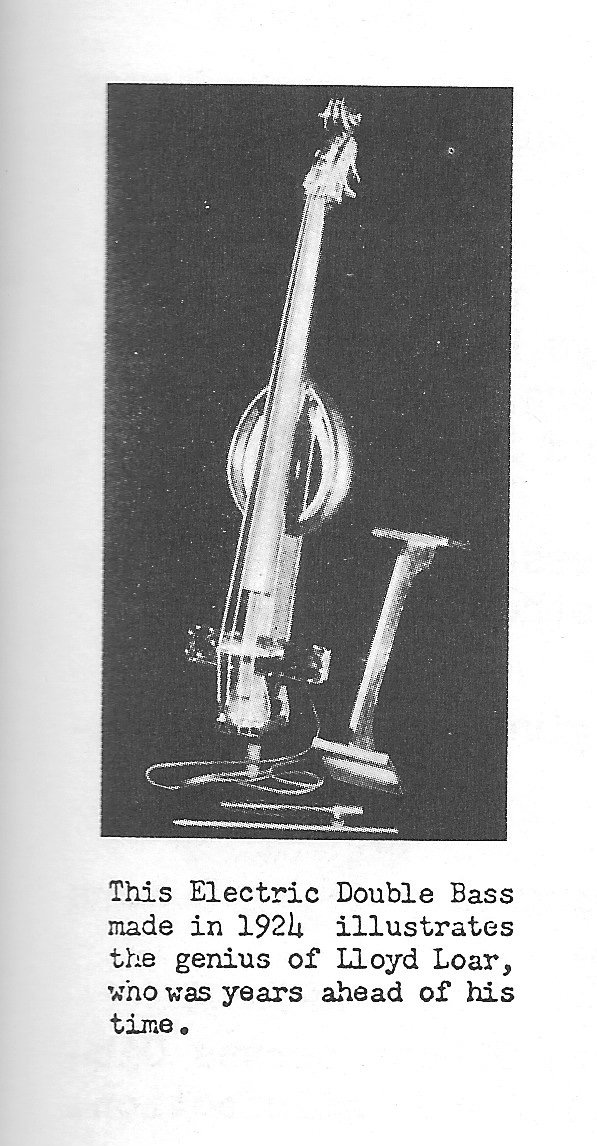

7) Loar was fired at the Board Meeting in January 1925 for inventing the electric bass

8) Someone else signed some or all the labels

Loar signature labels, L to R: Top, 72211 & 73753. Bottom, 75329 & 79834.

We find the idea that someone else signed the labels especially troubling as it is essentially an accusation of fraud. The evidence is based on variations in penmanship over the 31 month period. Granted, the pen or pen nib used does vary; for example, the signature on the labels from April 25, 1923 is different from most of the other labels. As we have discussed, on April 25, Loar was not at Gibson, he was in in Washington, D.C unveiling the F-5 mandolin to the public for the first time at the Guild Convention. A commemoration of that date on the mandolins exhibited there was a good marketing tool (See Breaking News 1923: A Capitol Idea). The Dec. 1, 1924 date was also written with a different pen or pen nib. (there are two L-5 guitars listed in the archives with dates after Loar left Gibson: 80262, December 21st—the Sunday when Loar was in Church in Brookfield—and 80263, December 31, New Years Eve 1924. Not only was the factory closed on these dates, but after an exhaustive investigation, it is our conclusion that these dates have been recorded incorrectly). We have provided labels from almost every signing date during the last three years, so the reader can scan those and make his own conclusions. We would also suggest that interested readers consider not only the writing of the signatures but the letters of the date as well; compare those with other labels of the same month. Below, we compare April 12, 1923 with the 25th; and December 20, 1922 and December 11, 1923 with December 1, 1924. In our opinion, the evidence points only to Mr. Loar and his busy pen(s).

Signature labels: On top, April 12, 1923; on left 72855, and 72857. Bottom, from April 25, 1923: 73006 and 73014.

Signature labels from December mandolins: On top left, December 20, 1922 71633 (photo courtesy Cody Schuler); top right, December 11, 1923, 74662. On bottom, two December 1, 1924 labels: on left, 79719 and right 79756.

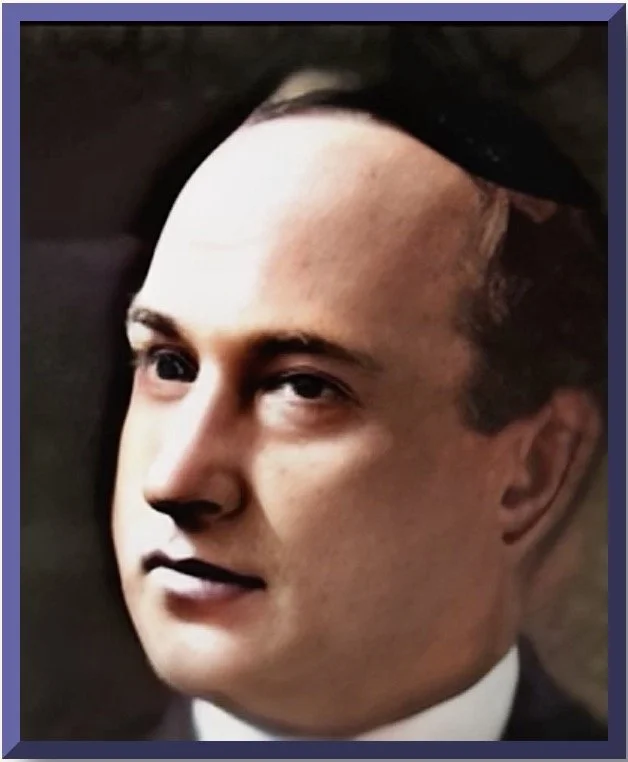

Loar, the Gibson years. left, promotional photo ca. 1916; center, April 1923; Right, circa 1927. Imagining the impact of the very stressful job of Factory Manager, one might suspect he was ready to leave in 1924.

Another controversy surrounds Lloyd Loar’s departure from Gibson. We have no primary source evidence of any ill will toward Gibson expressed or shown by Loar. This was another theme that first appeared in the 1970s. Even though his time at Gibson during his last year there may have been less than optimal for his artistic temperament, we have no evidence that his departure was anything other than professional. There is evidence that Loar had reason to have some level of satisfaction with his exit package, despite giving up rights to patents for his innovations while at Gibson.

1) In exchange for patent rights, Loar left with Gibson instruments, including an March 31, 1924 F-5, a TB-5, his 10-string MV-5, as well as tools and accessories. He continued to perform publicly with those instruments (when Walter Kaye Bauer broke with Gibson, he performed exclusively on Vega instruments and became a vocal detractor of anything Gibson; similarly, Bill Monroe gouged out "Gibson" from his peg head; David Grisman covers up his Gibson logo with a sticker).

2) In his agreement with Gibson, Loar retained rights to all articles, compositions, arrangements and music folios he composed while a Gibson employee. Many companies would have considered such work intellectual property.

3) Loar had received an administration level salary during his time of employment; he had also been paid for concerts and teaching that he did under the Gibson name; over the course of his tenure there, he had been awarded over 206 shares of Gibson stock, and continued to be a stock holder after he left.

3) Loar appeared at the Guild convention in Boston in 1927 playing his Gibson MV-5. He was featured on the cover of “The Mastertone” pamphlet along with Gibson endorsers like his friend William Place, Jr.

4) Gibson F-5 75315, Loar’s personal mandolin, was returned to the Gibson factory for new fingerboard, Grover tuners and “refresh” treatment (lacquer overspray, circa 1930). This indicates at least a continued respect for the work there.

5) “Vivi-Tone” and Gibson distributed through some of the same dealers such as Hartnett’s National Music Service in New York City in the 1930s.

In fact, after leaving Gibson, Lloyd Loar flourished as a writer, editor, inventor and lecturer. He continued to perform, but not in the grueling summer tours that he had undertaken in his earlier years. In many ways his authentic purpose and intellectual pursuits were more fulfilled after his time at Gibson, and as one writer said, "an hour with (Loar) is like a... liberal musical education."

Austin American, Austin, Texas November 22, 1933, p. 5. Lecture and concert took place on Wednesday, November 23, 1933.

In March of 2022, I began these episodes in an effort to observe the centennial of the birth of the F-5 mandolin and the history behind that momentous development in the world of mandolin. It started in conversations and exchange of documents with Steve Gilchrist. In fact, with every new document we found, Steve began to call it "Breaking News." I decided to compile those documents along with information I had collected over the past 50 years and share it with the mandolin community. Many folks became willing to send documents, information and encouragement, and to them I am deeply indebted. To that end, I have always credited each contributor. If you notice a photo that has not been credited, it is one I have personally taken, or if there is a document not credited, it is from my own collection. I ask that anyone who reproduces any item in this publication--text, photo, document or research--will also adhere to that professional courtesy and simply credit my effort.

A part of my energy that led me to this project was to examine the many Loar stories I had heard and understand what was true. I hope I have shed light and perhaps even dispelled some misinformation along the way. In my opinion, the story I have come up with is much more remarkable than the mythology. I hope you have enjoyed reading, and will come back to it from time to time.

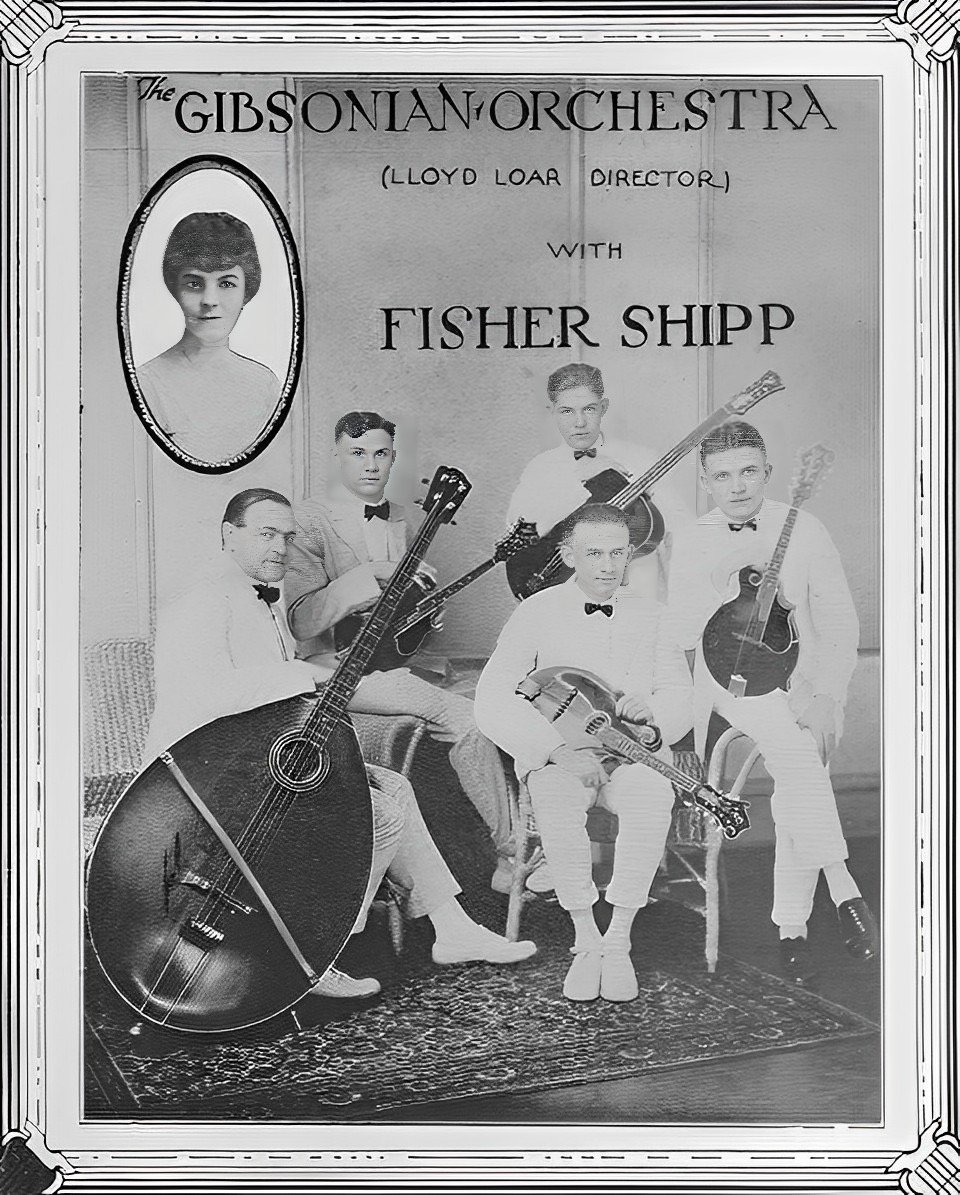

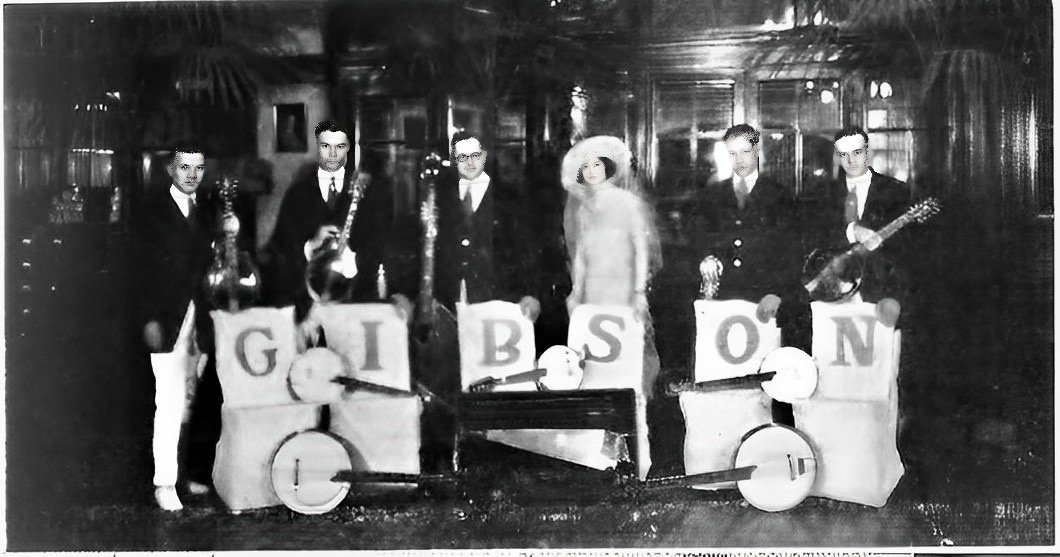

But first, some parting shots: I am grateful to able to offer the following photos restored and colorized by Cody Shuler (the gifted mandolinist with Pine Mountain Railroad), which I have arranged in a timeline of the Loar era at Gibson.

Promotional photo, ca. 1916. Photo restoration and color by Cody Shuler.

Promotional photo for the 1922 Gibsonians’ summer tour: L to R: James H. Johnstone, Francis Havens, Lloyd Loar, William Arthur Crookes (standing) and Walter Kaye Bauer. Photo restoration by Cody Shuler.

September 1, 1922, Grinnell’s Music Store, Detroit, Michigan. L to R: Walter Kaye Bauer, Francis Havens, James H. Johnstone, Fisher Shipp, W. Arthur Crookes and Lloyd Loar. Photo restoration by Cody Shuler.

Promotional photo for the 1923 Gibsonian tour (which began in April). L to R: Mrs. Ethyle Johnstone, C. A. Templeman, James H. Johnstone, LLoyd Loar and Marguerite Lichti. Photo restoration and color by Cody Shuler.

April 23, 1923. L to R: Marguerite Lichti, Mrs. Ethyle Johnstone, James H. Johnstone, C. A. Templeman, Lloyd Loar. Photo restoration and color by Cody Shuler.

Promotional photo for the 1924 Gibsonian tour (which began in April.) L to R: Lloyd Loar, Dorothy Crane, Fisher Shipp-Loar, James H. Johnstone, Nell VerCies, Lucille Campbell. Photo restoration by Cody Shuler.

I wish to thank my faithful readers, and send gratitude to those who have replied with encouragement and/or information. Special thanks to Stephen Gilchrist, Randy Wood, Roger Siminoff, Darryl Wolfe, Dan Beimborn (Mandolin Archive), Tom Isenhour, David Grisman, Harry Bickel, Wayne Joyce, Dan Weinstock, George Gruhn, Walter Carter, Joe Spann, Cody Shuler, Charley Rappaport, Rick Taylor, and Harry Sparks. A special thanks to Scott Tichenor for sharing my writings with his readers on Mandolin Cafe. Finally, I wish to thank the noted medical author and editor, Andrea Deyrup, MD., PhD., for her editing skills and for her patience with me as I obsessed with this material for these last three years. To be clear, any mistakes, grammatical and otherwise, are mine and mine alone.

Many readers have inquired as to if and when my writings on Lloyd Loar might be available in a hard copy book. I assure you, I would love for such a volume to be on your coffee table and mine. We will see what the future holds and how the logistics of such a publication might unfold.

But for now, I am signing off.

Tony Williamson, December 1, 2024.