Walter Kaye Bauer, ca. 1921, with new Gibson F-4. He would perform the First Mandolin parts with the 1922 Gibsonians. (Photo courtesy Jeff Foxall)

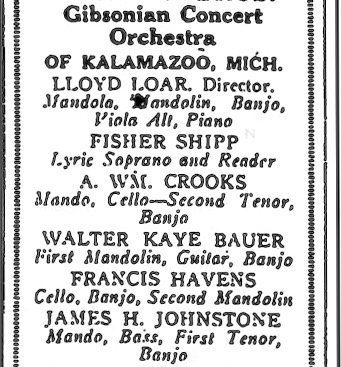

Detroit Free Press, Detroit, Michigan, Sep 1, 1922

Walter Kaye Bauer, born May 21, 1899, was twenty-two years old when he met with Lloyd Loar at the Guild Convention in New York City. A mandolin prodigy as well as accomplished actor, he had been the star pupil of the great Samuel Siegal. By 1919, with his partner Arthur William Crookes, he had created Bauer Studios at 19 Central Row in their hometown of Hartford, Connecticut, teaching mandolin family instruments as well as guitar and banjo. Bauer was an ideal candidate for the Gibson artist-teacher-agent program, and the perfect choice for First Mandolin in the Gibsonian Concert Orchestra, which was scheduled to begin touring on June 15, 1922. Unlike his mentor Siegal, he had put aside the bowl back in favor of the Gibson mandolin and also had become a champion of Gibson’s tenor banjos. (Siegal, no doubt distraught with the direction American music was taking, had moved to London by 1924 and for the next decade performed classical mandolin to enthusiastic audiences across Europe [P. J. Bone, The Guitar and Mandolin, p. 332]). Bauer and Crookes had also established the Hartford Symphony Mandolin Orchestra, which, by May of 1922, had twenty-six musicians well supplied with Gibson instruments.

Hartford Courant, Hartford, Connecticut, Jun 3, 1922 · Page 12.

By the time Bauer toured with Lloyd Loar, he had already accomplished much. At age 15, he showed great promise in the theatre, and so accepted an opportunity to go New York City to seek his fortune. In 1916, he landed a leading role in “The Royal Pauper,” a production for the Thomas A. Edison Motion Picture Company. He played William, a “Prince Charming” character, opposite seventeen-year-old Francine Larrimore, who starred as Irene, the “Princess.” Released on February 19, 1917, the tale of rags-to-riches and true love delighted audiences from New York to Los Angeles, and drew national attention to the young stars. Like Miss Larrimore, Bauer continued to pursue his career in New York City, accepting a second leading role, this time on Broadway in the Henry Harris production, “Easy Come, Easy Go.” For the next decade, Francine Larrimore flourished as an acclaimed actress, famously creating the role of “Roxie” in the 1926 Broadway debut of Chicago.

Advertisement for “The Royal Pauper” seen in newspapers across the US in 1917.

Promotional photographs for the stars of “The Royal Pauper,” 1917: Francine Larrimore and Walter Kaye Bauer.

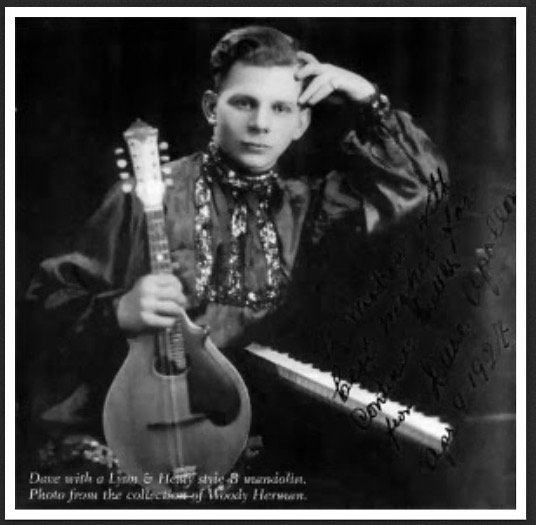

While in New York, Walter studied mandolin with Samuel Siegal, and was cast in a few more silent movies and Broadway shows. “After a poor season, he moved back home, became a reporter for the Hartford Times and studied guitar with Annie K. Pfund and banjo with Mr. Pfund and Frederick Bacon” (Crescendo, November, 1922). Blending his love of music with theatre, he also became a Vaudeville performer on the Poli Circuit. The brainchild of Italian immigrant and entrepreneur Sylvester Zefferino Poli, the Poli Circuit was a series of over 30 theaters that offered movies interspersed with Vaudeville actors, comedians and musicians. The vaudevillians appeared in Poli theaters in Waterbury, Bridgeport, Meriden and Hartford Connecticut; Springfield and Worcester, Massachusetts; Jersey City, NJ; Wilkes-Barre and Scranton, PA, and Washington, DC. It was on the Poli Circuit that Walter shared the bill and became friends with the brilliant mandolinist Dave Apollon.

David Apollon, photo ca. 1920, with Lyon and Healy “B” mandolin.

Letter from Dave Apollon to Walter Kaye Bauer, 1956, recalling the Poli Circuit. (Courtesy Jeff Foxall, private collection)

The Bauer Players: Walter Kaye Bauer, First Mandolin (Gibson F-2); D. A. Winans, Second Mandolin (Gibson A-2); Arthur William Crookes, Mandola (Gibson H-2); George G. Pillar, Mandocello (Gibson K-1); Raymond J. Surewick, Harp-Guitar (Gibson U). (The Crescendo, November, 1920).

By the time Bauer joined Lloyd Loar, Fisher Shipp and the Gibsonian Concert Orchestra, he had achieved a significant command of the mandolin. An article in The Crescendo, probably written around May of 1922 (but not published until the November 1922 issue), describes Walter’s repertoire:

“The mandolin…is Mr. Bauer’s favorite instrument. He has a large and varied repertoire, including works of Munier, Calace, Marucelli, Mezzacapo, Arienzo, Siegal, Abt, Pettine and others. At present Mr. Bauer is studying harmony and composition under Dr. Robert H. Prutting. Accompanied by his partner, Arthur Wm. Crookes, Mr. Bauer is touring the West this summer with the Lloyd Loar company, ‘The Gibsonians,’ in lyceum work as mandolin soloist. Mr. Crookes will feature the mandocello. They will return about September 10 and open their studios in Hartford and Willimantic.”

Walter loved to tell stories of his time as a young man in New York City. He was equally fond of recalling the inspiration he received from Samuel Siegal. “My teacher, the famous Sam Siegal, used to say, ‘The plectrum is the tongue of the instrument. Control it like you do your own tongue.’” (Walter Kaye Bauer, “A Century of Musical Humor,” Plucked String, 1988.)

Samuel Siegal, 1918.

At Christmas, 1989, Walter sent this author his arrangement of Giuseppe Silvestri’s “Telephone Waltz” with the following handwritten inscription: “When my teacher toured Europe in the 1890’s, the telephone was comparatively new. He (Samuel Siegal) was playing his last date in Firenze (Florence), Italy. That night 125 mandolinists under the direction of the composer of this piece gathered outside his hotel window and gave him a ‘mandolinata.’” Bear in mind that Giuseppe Silvestri was a celebrated Italian mandolin virtuoso and composer—the star of the Paris Exposition of 1878 (Paul Sparks, The Classical Mandolin, p.22-23), while Samuel Siegal was from Des Moines, Iowa, and had no formal training in music. Despite any limitations from being self-taught, or perhaps because of it, Siegal had taken the world of mandolin by storm!

Bauer arrangement of “Telephone Waltz” page 1; the entire arrangement along with a letter was sent from Walter Kaye Bauer to Tony Williamson in December of 1989.