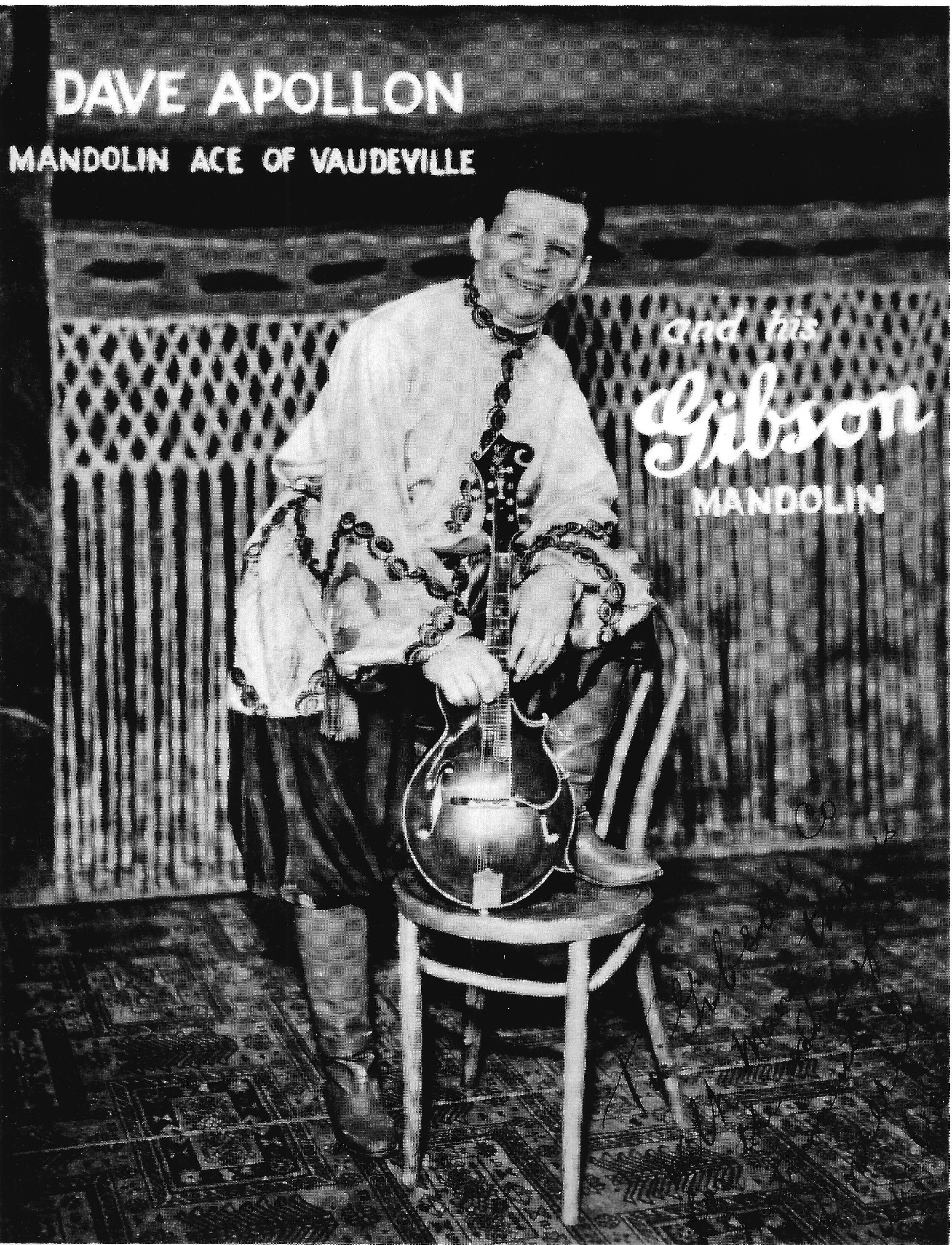

Miami Herald Sun, January 7, 1945. One of two posters created for the concert at the Orange Bowl.

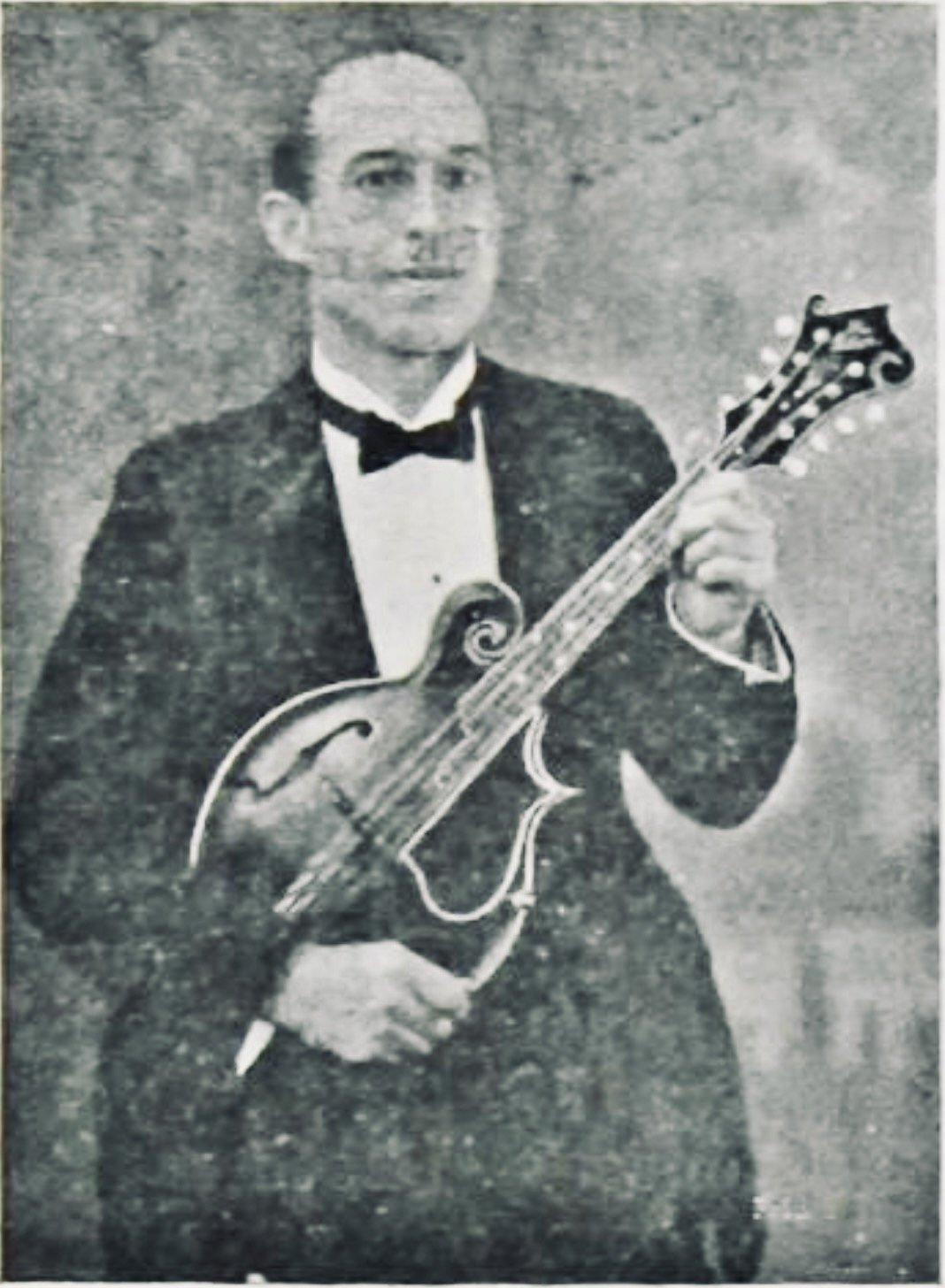

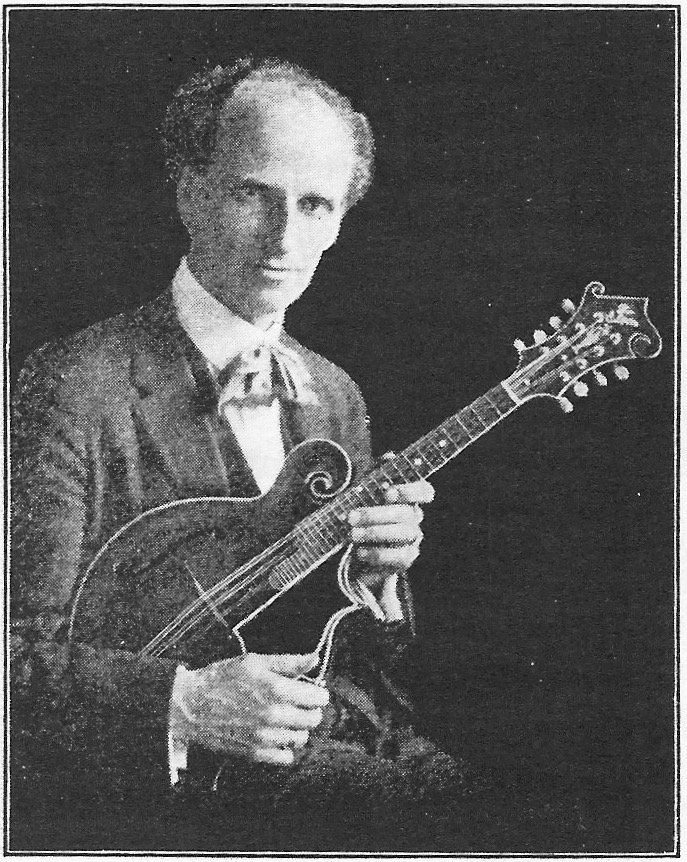

William Smith Monroe, 1945, shortly after acquiring Gibson F-5 73987, signed by Lloyd Loar on July 9, 1923.

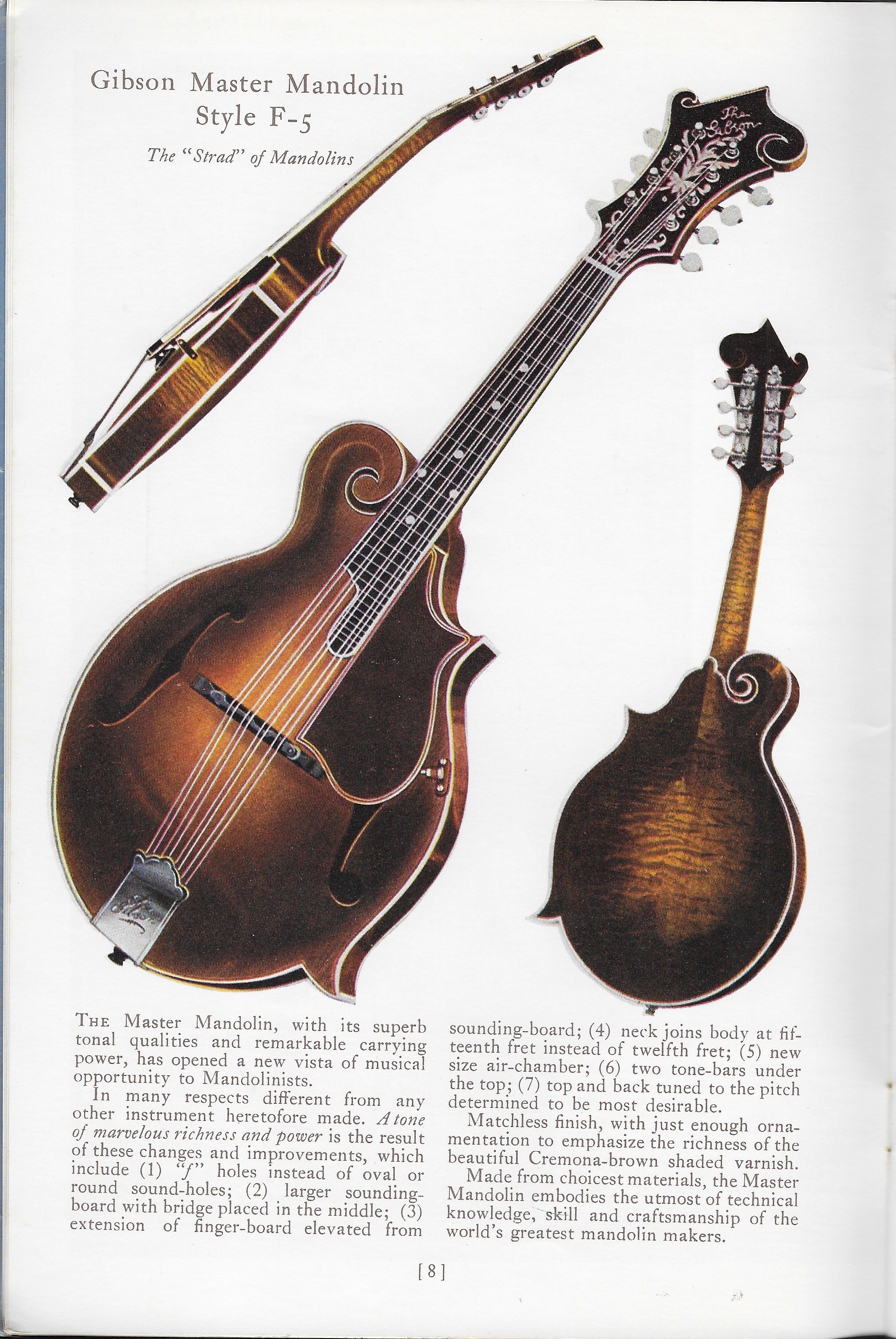

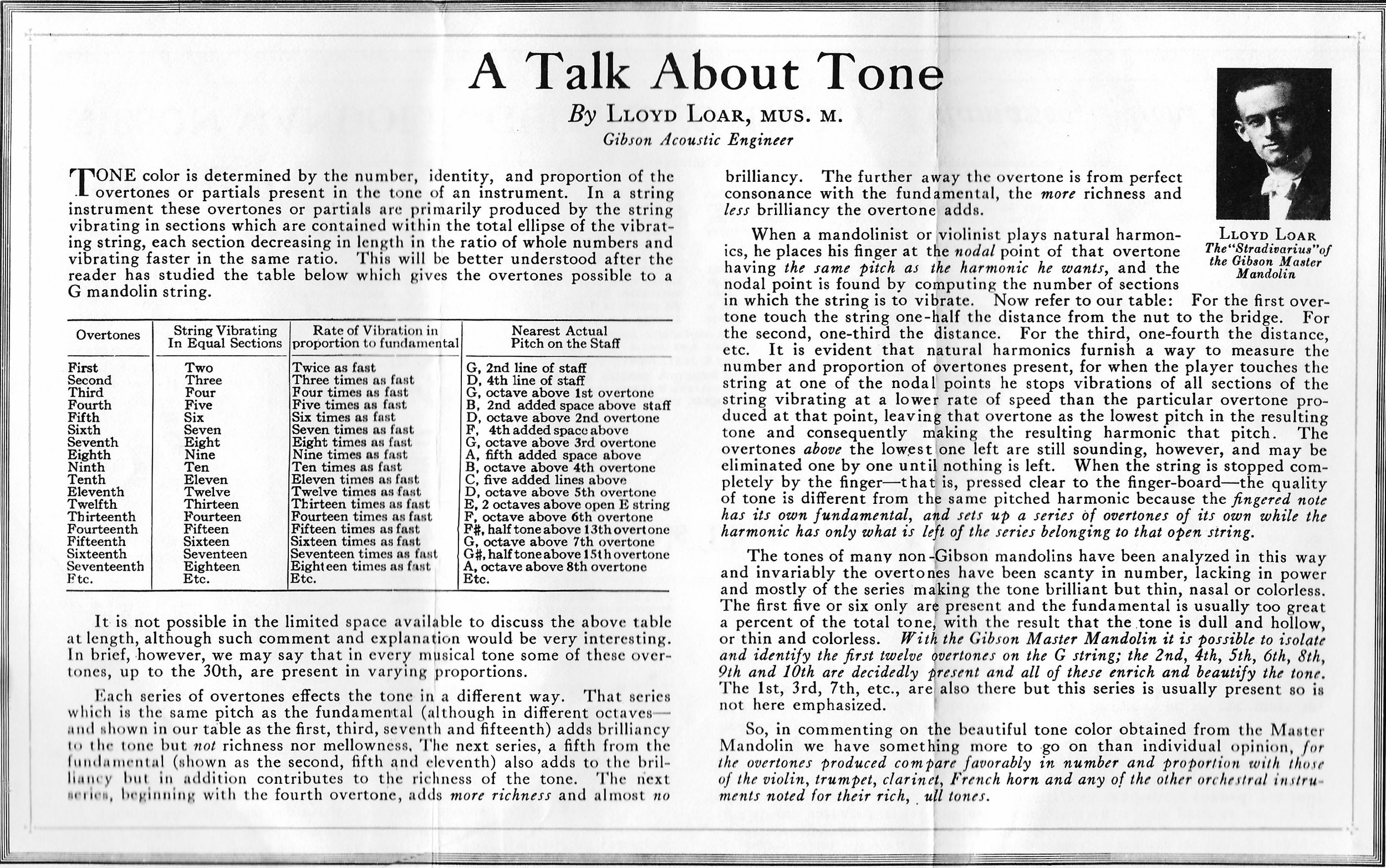

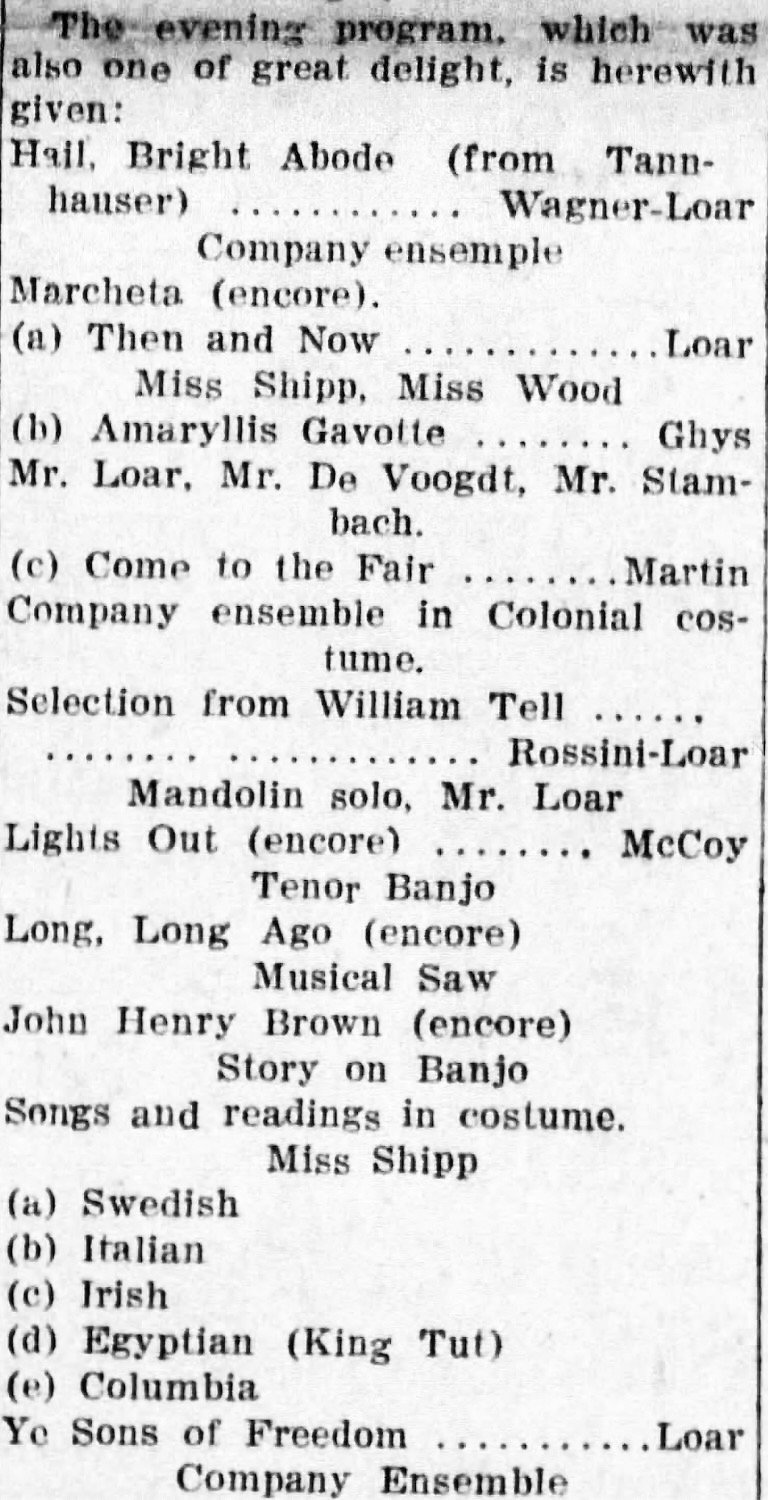

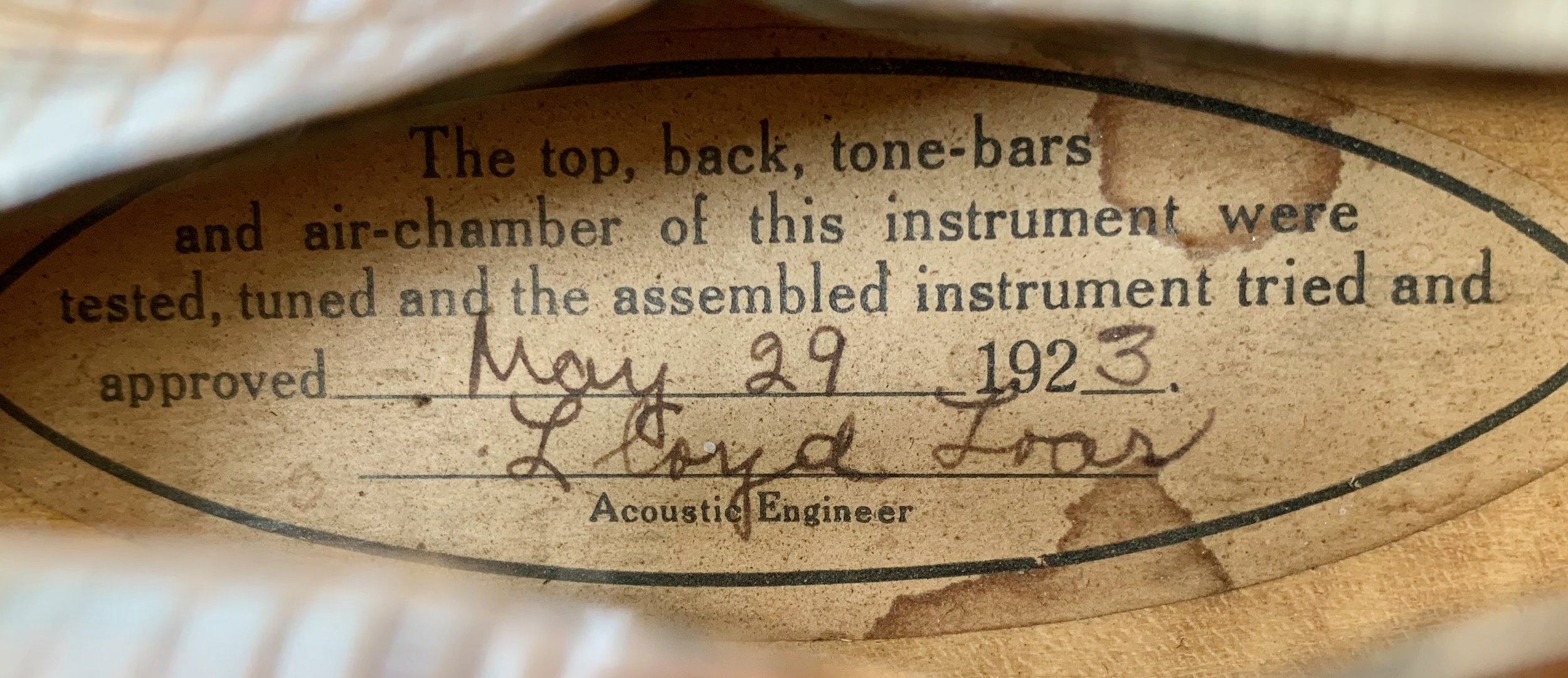

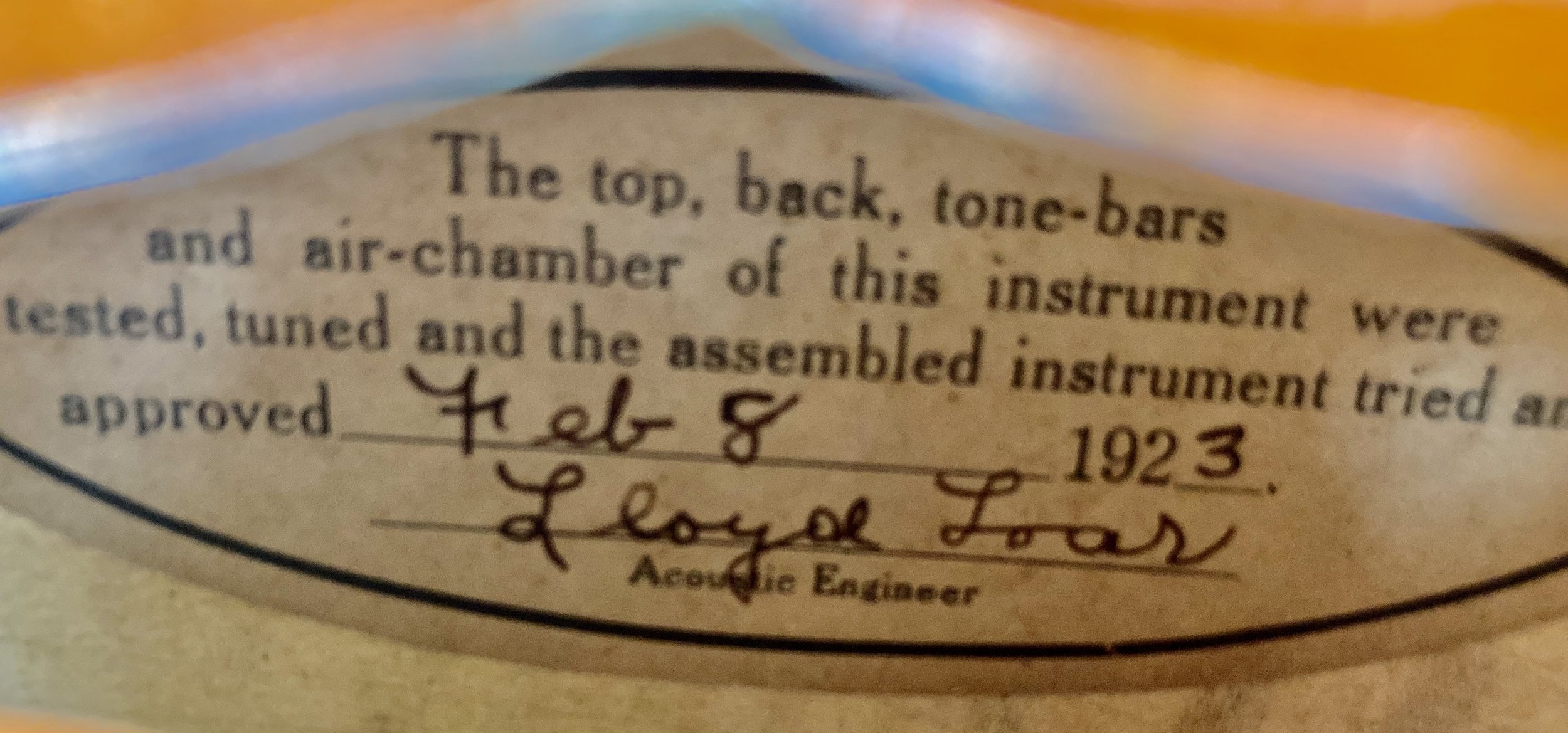

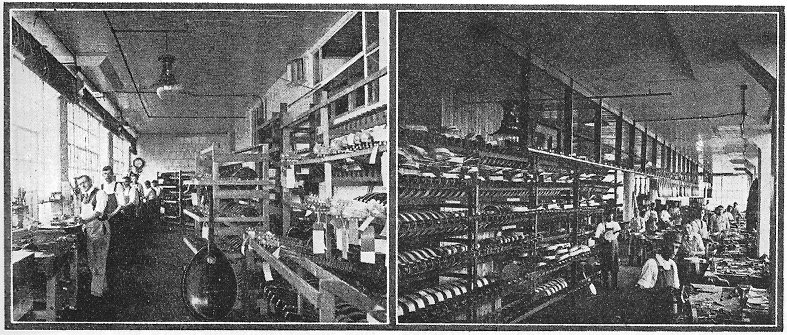

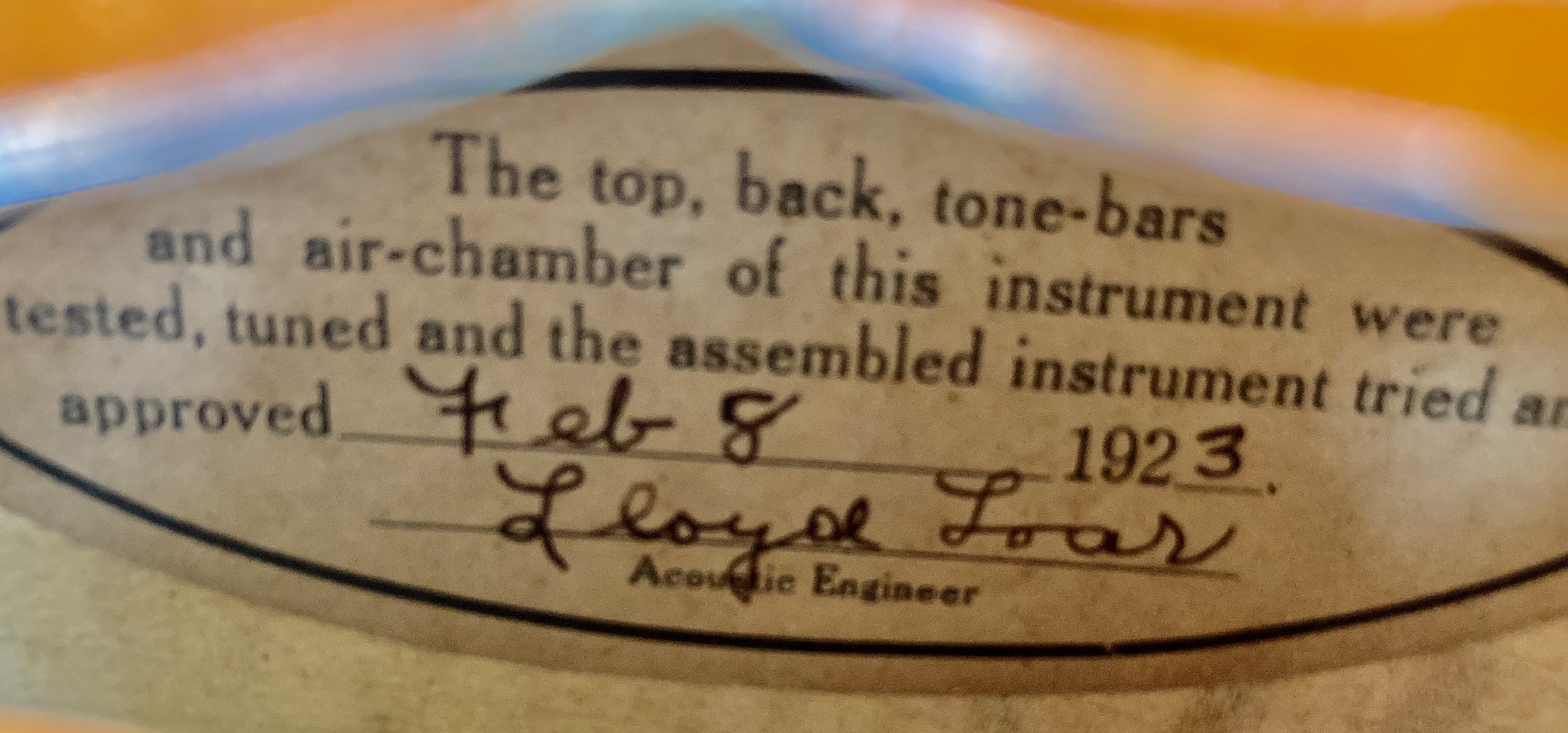

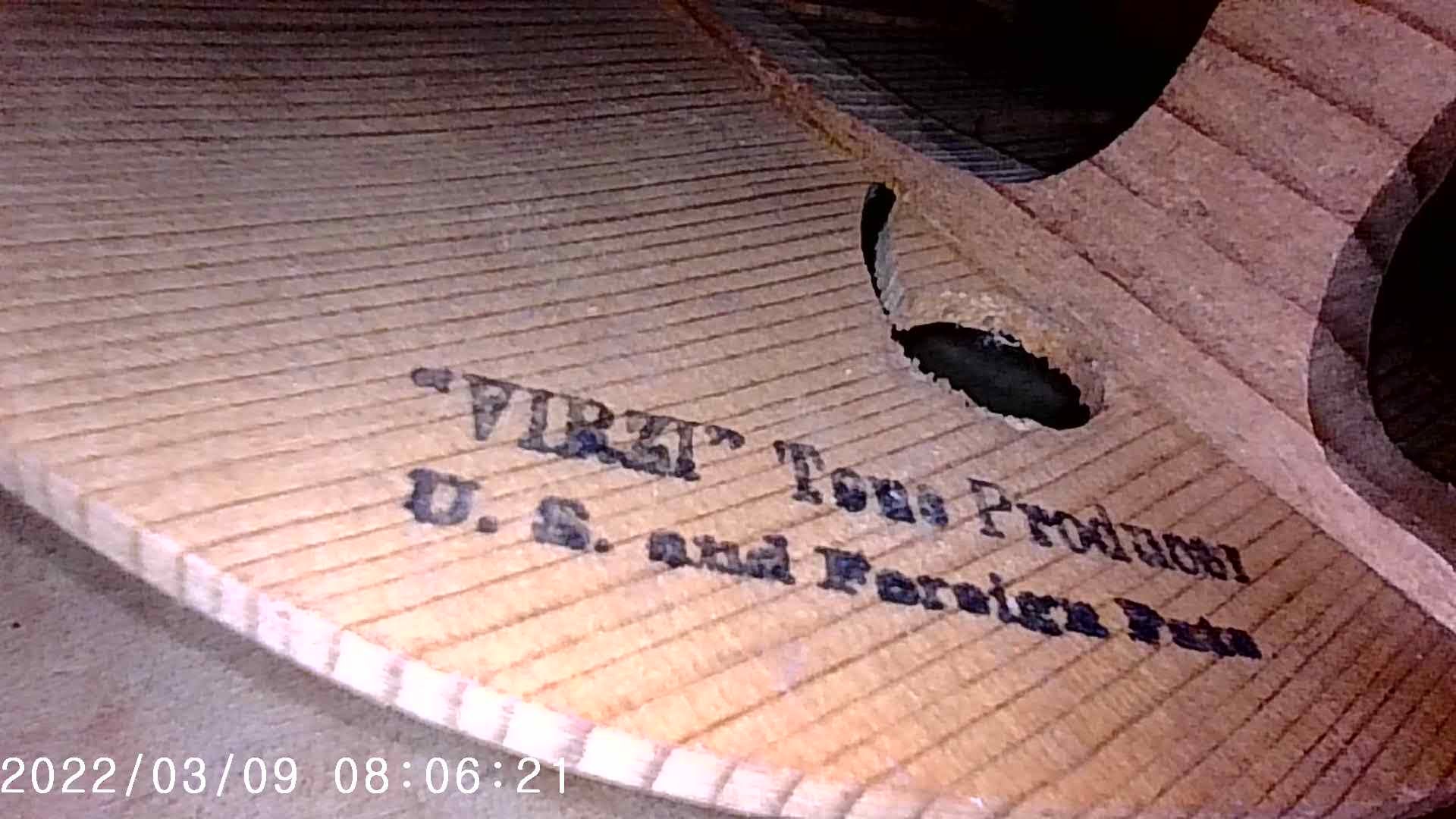

Did the F-5 mandolin make Bill Monroe, or did Bill Monroe make the F-5 mandolin? Either way, July 9, 1923, is a storied date, one that has made a tremendous impact on the century of the Gibson F-5. Bill Monroe scholars understand the significance of the poster above and how the extraordinary event of January 11, 1945, relates to what happened in Kalamazoo 22 1/2 years earlier. This episode will delve deeply into our study of posters, newspapers ads and articles and other primary sources, but first we must examine the mandolins themselves. The group of F-5s dated July 9, 1923, was the largest to date. With two sets of sequential numbers with similar appointments, 73719 to 73733 and 73747 to 73755 (a total of 22 mandolins) and a third sequence, 73980 to 74002, (also 22 mandolins), we are tempted to proclaim a total of 44 F-5s were finished and signed, ready to ship. Not all 44 numbers are accounted for today, so there is an enticing possibility that some are still to be discovered. An interesting side note, the latter sequence of numbers all exhibit a curious change in the installation of the top and back binding: the 3-ply binding is oriented so that the center ply, a black stripe, appears on the side instead of the top. From a production point-of-view, we consider this a separate batch, the legendary side-bound F-5.

Scrolls on two F-5s dated July 9, 1923. Left: 73753 with standard binding; Right, 73994 with black stripe on side

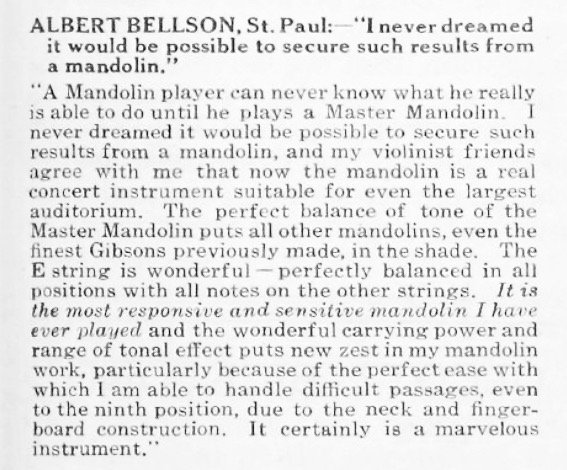

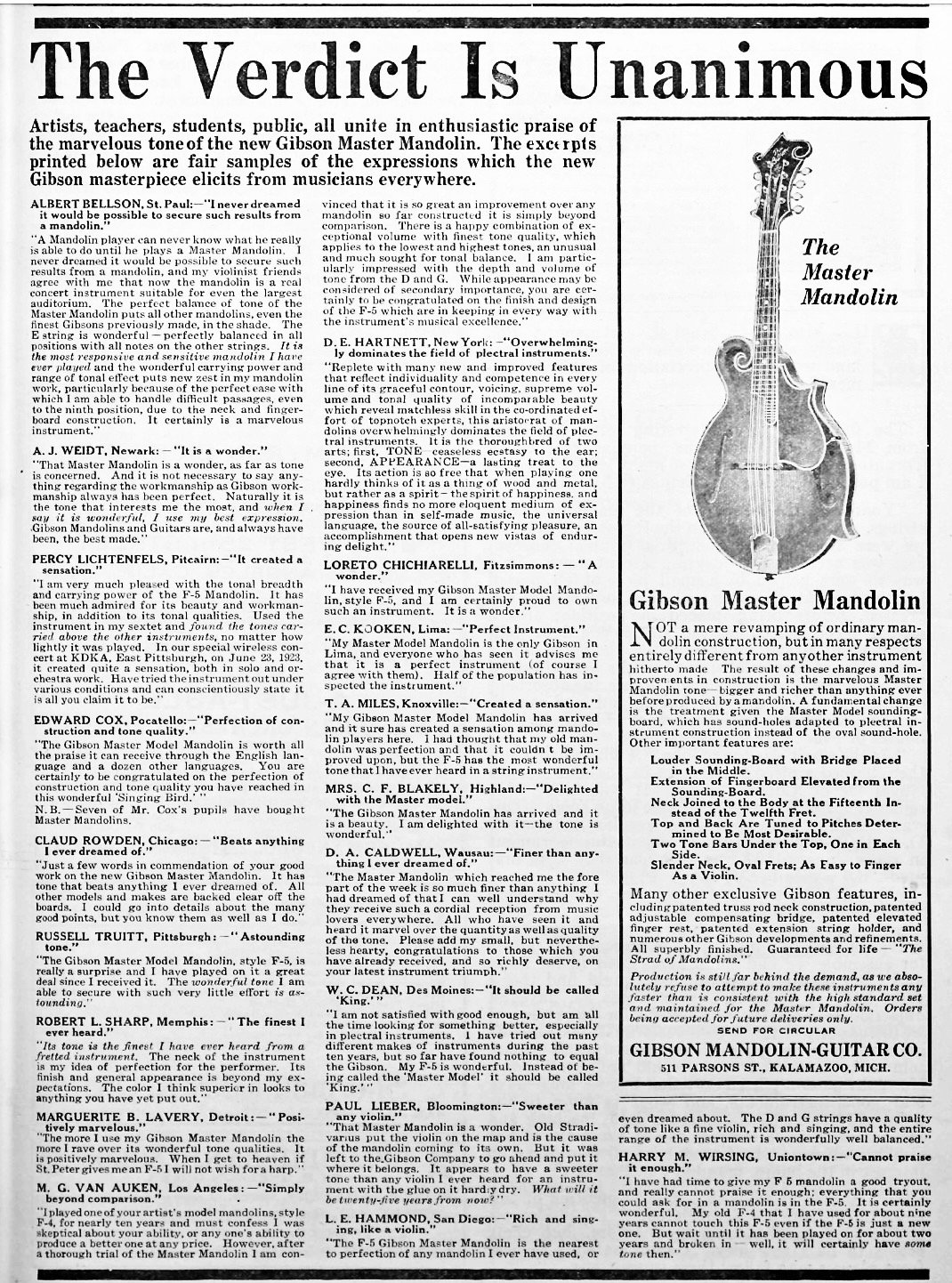

Before our imagination runs wild and we go out searching for the missing mandolins, we should start at the beginning. The first mandolin to receive the July 9, 1923, date was F-5 #73719, sold to Albert Bellson of St. Paul, Minnesota. Mr. Bellson, who had favored model F-4 (with his characteristic bone saddle to improve brightness), wrote to Gibson soon after receiving the F-5 which he played for the rest of his career.

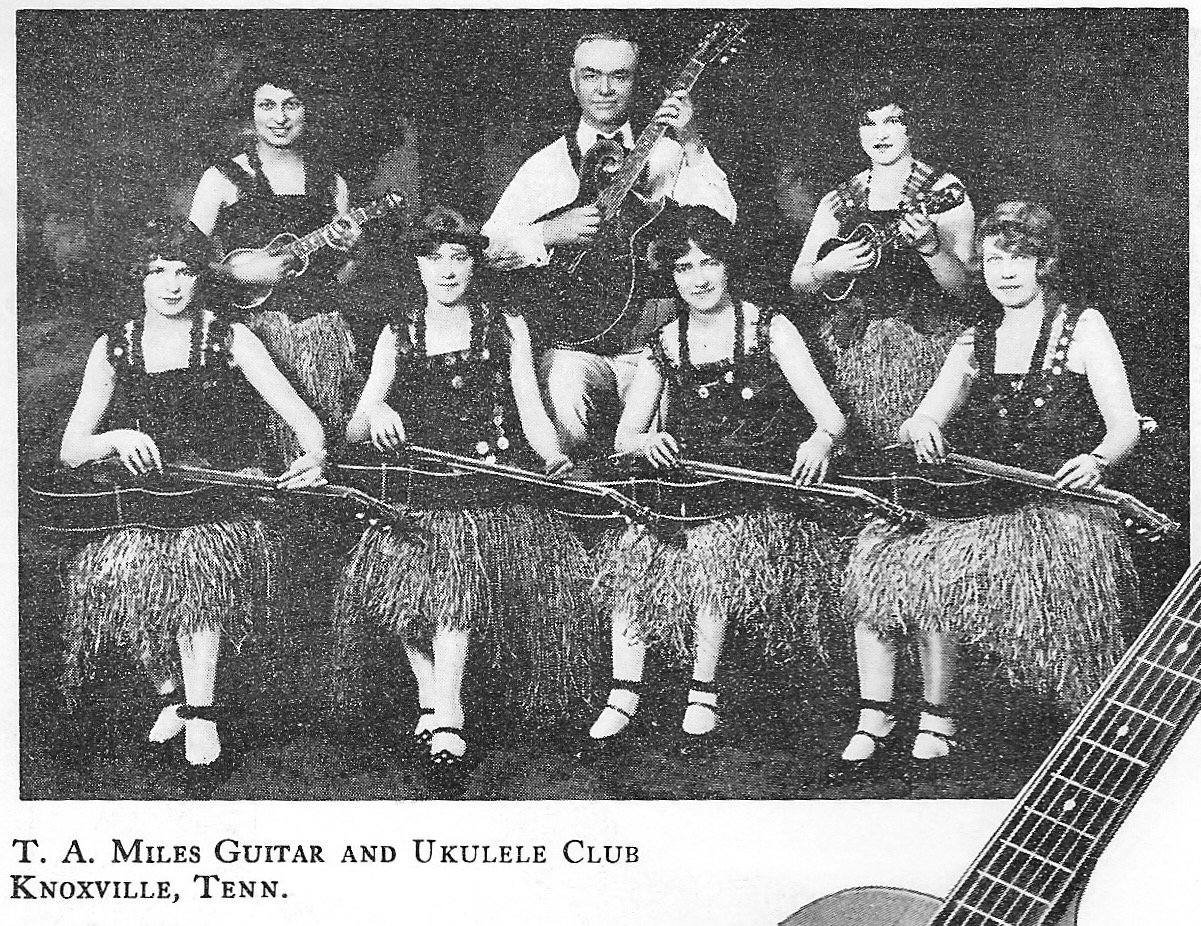

Letter to Gibson from Albert Bellson, published in The Crescendo, October, 1923, p. 19.

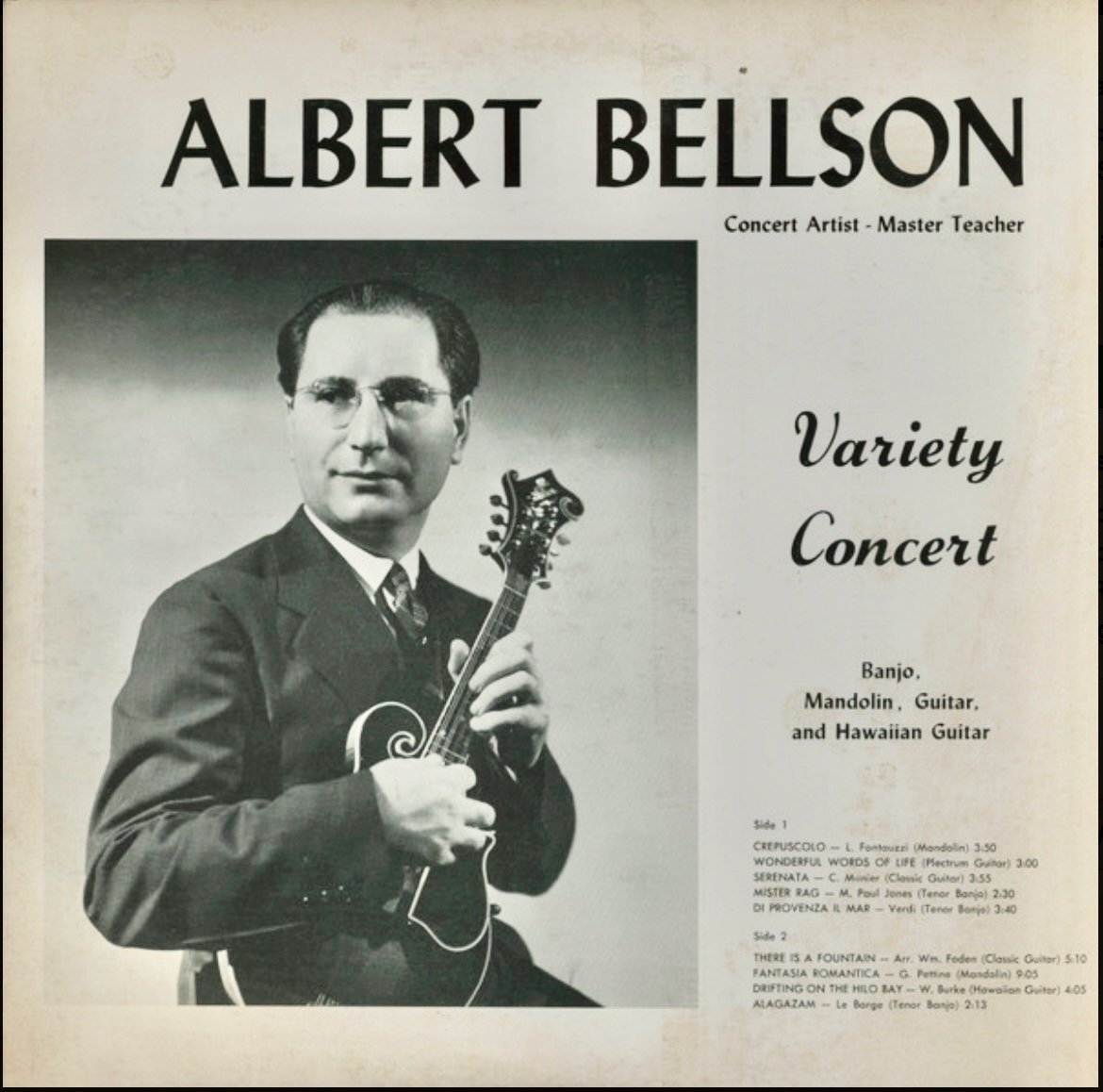

Albert Bellson with F-5 #73719, dated July 9, 1923. Cover of Bellson’s Long Play vinyl record album, released in 1966.

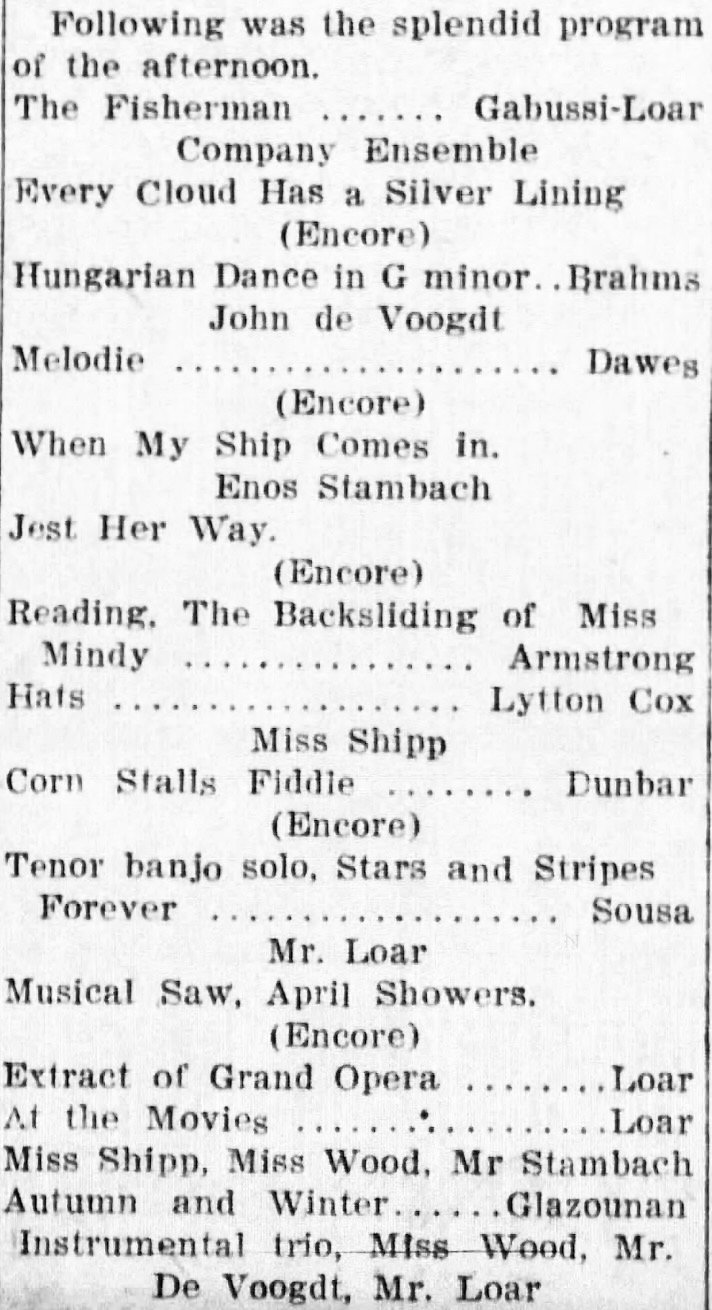

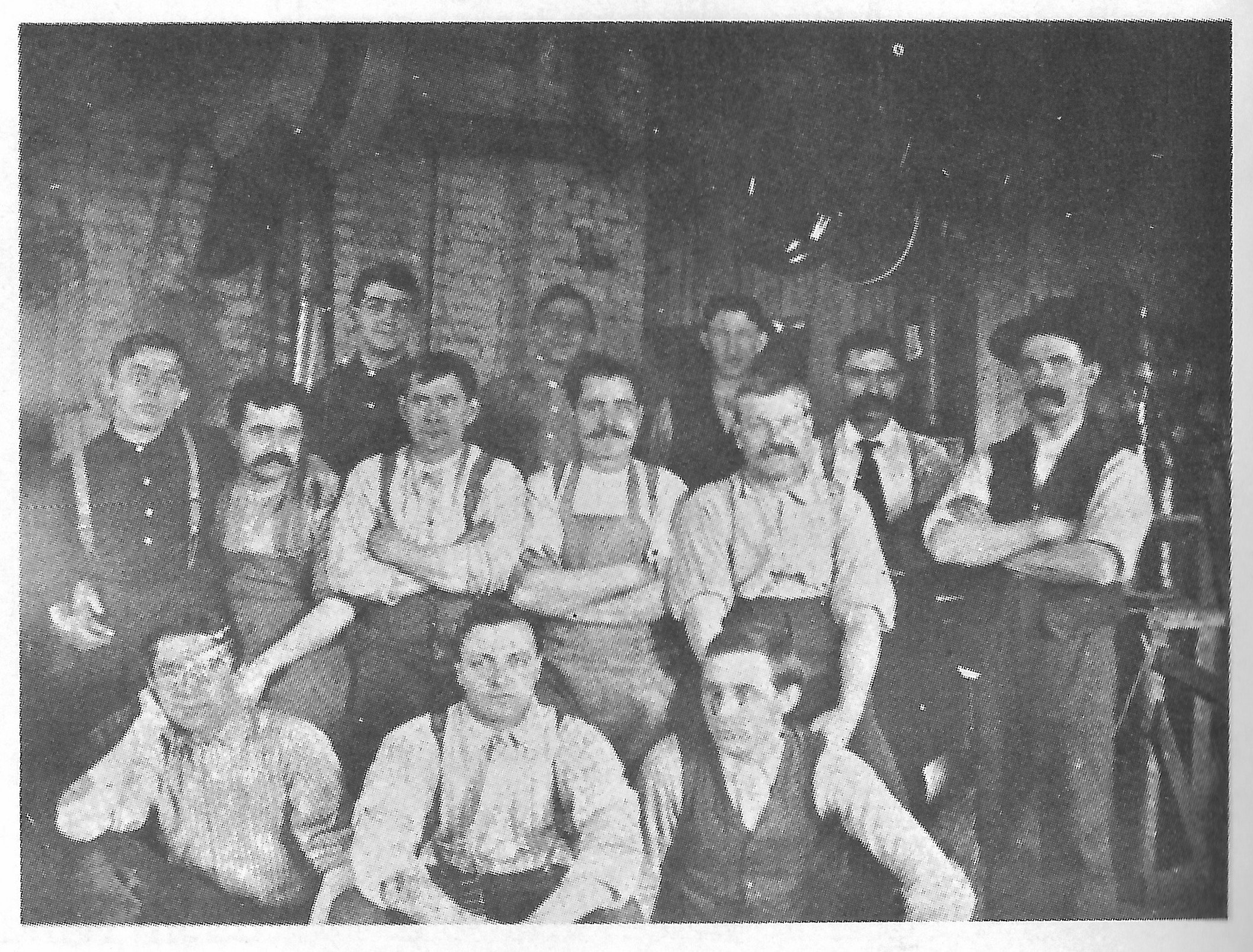

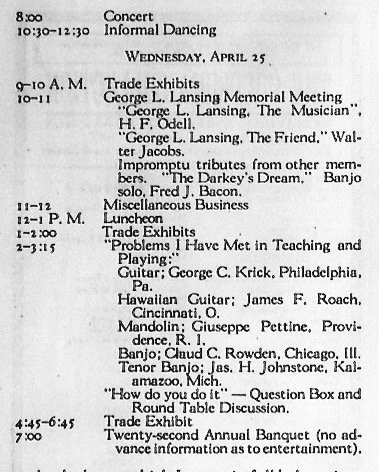

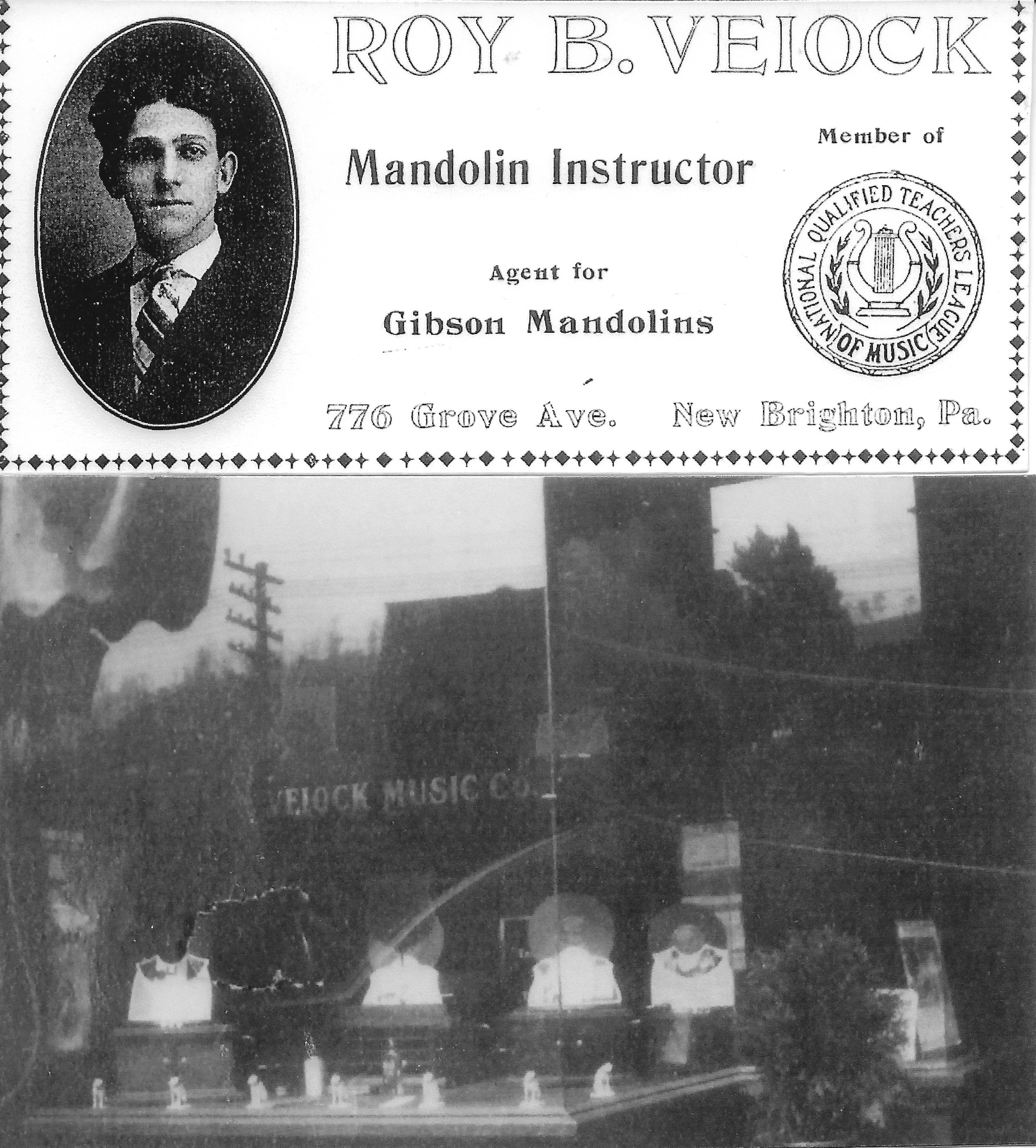

Alfonso Bellasone was born in St Angelo, Sicily, Italy, on March 6, 1897. (Readers of “Breaking News” will recall that St. Angelo was also the home of the Virzi Brothers). He and baby brother Julius were brought by their parents on the ship Citti di Napoli to New York City on December 4, 1906. Alfonso’s name was recast as Albert Bellson on June 26, 1920, when he received his naturalization papers in Providence, Rhode Island, witnessed by none other than mandolin maestro Guiseppe Pettine. Pettine had welcomed the brothers as students, having recognized their remarkable musical gifts. Unlike his teacher, Albert embraced Gibson mandolins, possibly influenced by fellow Pettine student William Place, Jr. Spreading his musical wings, Bellson not only became a Gibson artist/teacher/endorser, but the leader of the 1921 Gibsonians (also examined in “Breaking News 1922”), sharing the stage with James H. Johnstone and the brilliant Leora Haight. When the Gibsonians performed at the Guild convention in Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Times listed Bellson along with Lloyd Loar as “Greatest Solo Artists In America.”

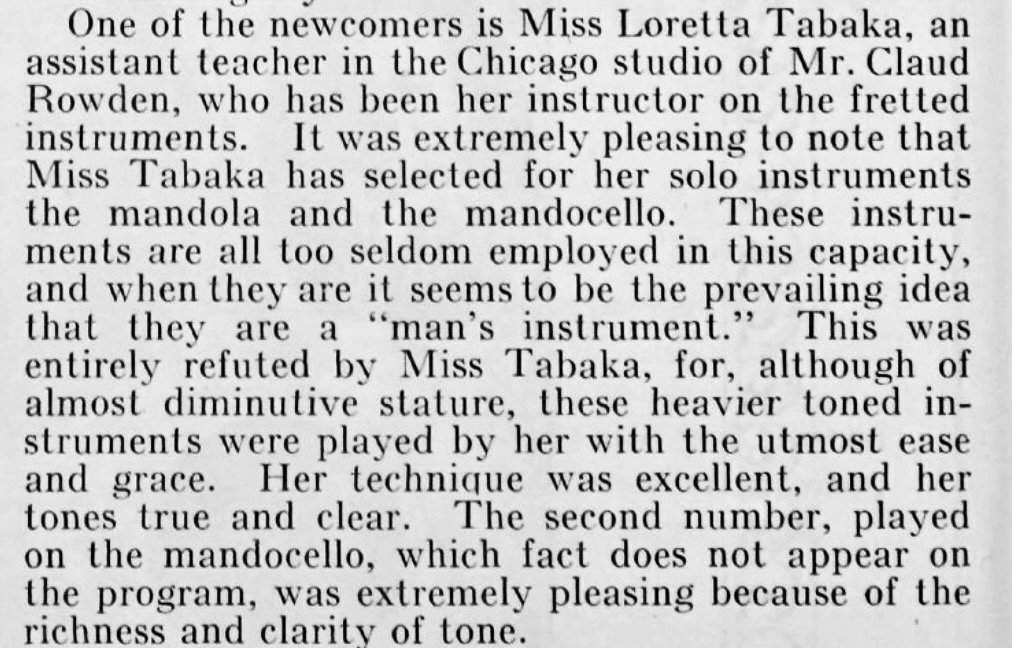

Los Angeles Evening Express, June 23, 1921_

After Lloyd Loar and Fisher Shipp were invited to headline the Gibsonian Concert Orchestra in 1922, Bellson moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, and began building a clientele of students, offering lessons on “mandolin, banjo and ukulele.” Bellson School Of Music on 474 Collins St. opened in September of 1923, and remained an important center for music studies in that area for the next thirty years. A confirmed Gibsonian, Bellson populated his orchestra and quartet with the finest instruments his students could afford, including Master Models. One of his most talented pupils, Wallace Ziebarth, acquired Gibson F-5 # 72857, signed by Lloyd Loar on April 12, 1923, and perhaps this instrument inspired Bellson to order F-5 73719. Another star pupil was Vergel Viola Anderson. Born January 1, 1909 in Isanti, Minnesota, she came to the Bellson studios for instruction on mandolin as a teenager. Evolving into a brilliant proponent of the mandola as both teacher and performer, she chose the stage name Vergel Vanzora, and was known, like Lloyd Loar, for expanding the possibilities of the tenor voice of the mandolin family. She acquired a Gibson H-5 Master Model Mandola even before she became Mrs. Bellson in 1928.

Standing, Wallace Ziebarth with F-5 #72857; Clifton Peterson, K-1 mandocello; Seated, Albert Bellson with F-5 73719 and Vergel Vanzora with H-2 mandola.

Viola Anderson, stage name Vergel Vandoza, ca. 1924.

Vergel Vandoza with her Gibson H-5 Mandola.

Another woman who pioneered the Master Model F-5 in her community in the 1920s was Mrs. Julius Blakely of Highland, New York. Born Florence Clearwater in Lloyd, New York, in 1875, she was an English teacher and amateur mandolin player when she met her husband, Dr. Blakely. They were married on September 21, 1913, and she fulfilled her musical aspirations with local events, mandolin clubs, charity fundraisers and church performances. Thanks to her husband’s occupation, which provided a $15,000 home for her parlor concerts, she was able to afford the F-5 when it became available in the summer of 1923. She, like several of the new owners, wrote to Gibson: “The Gibson Master Mandolin has arrived and it is a beauty. I am delighted with it—the tone is wonderful.”

Mrs. Blakely’s Gibson F-5 73741 surfaced again in upstate New York in the late 1970s. This strong and dynamic sounding instrument is ready to find another good home for the next century.

Twenty-six year old Harry M. Wirsing left his mandolin at home when he was inducted into the US Army on February 22, 1918. He served in Company I, 112th Infantry, and fought against the German invasion in the horrific trenches in France. Wounded in action, he landed in Philadelphia on April 30, 1919, and by 1923 had a thriving music shop on 8 Seaton Avenue in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, where he gave lessons and sold Gibson instruments. When he got his F-5, praise flowed from his pen:

Letter to Gibson published in The Crescendo, October 1923.

We have many more stories of the first owners of 1923 F-5s, and plan to share them in future episodes. However, on this auspicious date, we now return to the incredible event we alluded to at the outset of this episode.

Miami New, Wednesday, January 10, 1945.

In the years from 1939 through 1942, Bill Monroe and The Bluegrass Boys rocketed into the top echelon of hillbilly entertainers. Along with Roy Acuff, he was the headliner on the nationwide broadcast, The Grande Ole Opry, which blasted out of Nashville, Tennessee, with 50,000 Watts on WSM Radio each Saturday night. Played to a packed house at the 3500-seat Ryman Auditorium, these shows, which were also carried by NBC affiliates, captured the excitement and electricity of Bill Monroe’s performances and transported it to living rooms all across North America. Throughout the 1940s, Monroe ruled the airwaves with two Saturday night spots: 8pm to 8:30, sponsored by Purina, and 10pm to 10:15, sponsored by Wallite. Afterwards, and often immediately after, Monroe’s 1941 Chevrolet Airport Limousine led an impressive caravan of automobiles carrying musicians, comedians, instruments, a circus tent and even a baseball team across the southern United States. They travelled and performed Sunday until Friday, after which they always made it back to Nashville for the Saturday night Opry. Passionate fans driven by those broadcasts poured out to hear the show when Bill Monroe came to their town.

Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys, autumn 1944. Left to right: Curley Bradshaw, “Sally Ann,” Monroe, Chubby Wise, Clyde Moody and “Stringbeans.”

On May 15, 1942, a great deal changed for traveling entertainers when the US government began rationing gas and rubber for the war effort. Gas stickers were granted based on how an individual contributed to the war effort. The “A” sticker entitled a car owner to 4 gallons a week and the “B” sticker, only 3 gallons. It is unclear how Bill Monroe managed to keep his automobiles on the road, but somehow he made personal appearances in Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama and Kentucky in 1943 and 44. For reasons that had nothing to do with the war, the American Federation of Musicians called for a ban on all recording beginning on August 11, 1942, and negotiations dragged on until November 11, 1944. Columbia records had signed Monroe before the ban, but had to wait to record him. (It was on February 13, 1945, at the CBS studios in the Wriggly Building in Chicago, Illinois, that Monroe kicked off his first recording session for that company with “Rocky Road Blues”). Despite the impact of these limitations, Bill Monroe still seemed to flourish. All the way down in southern Florida, NBC affiliate WIOD in Miami carried his show live every Saturday night during those years, and the Miami News and Miami Herald both carried notices reminding people to listen for Bill Monroe. Articles promised that “Bill will be singing the Mule Skinner Blues!” Or, “you will hear favorites like ‘Arkansas Traveler,’ ‘The Girl I Love Don’t Pay Me No Mind,’ ‘Black Jack Davie’ and ‘Katy Hill.’” Just as often, they would proclaim that the Bluegrass Quartet will be singing “religious numbers like ‘I Found A Hiding Place.’”

Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys, October, 1944: Standing L to R: Clyde Moody and Bill Monroe; Front row: Howard Watts, “Sally Ann,” Chubby Wise, “Stringbeans.”

Immediately after the Opry show on January 7, 1945, Bill Monroe and a huge entourage drove out of Nashville headed for south Florida, his first trip that far south. Earl Scruggs made that same journey with The Bluegrass Boys one year later. In an interview with this author in January, 2007, Scruggs recalled his first trip as a Bluegrass Boy: “When we left Nashville that night after playing the Opry, we struggled through winter weather on two lane roads, some not paved, to make it to Atlanta around daylight. In Atlanta there were 93 stoplights. By the time I left Bill, I knew every one of them by heart. The lights were timed so that if hit you the first one just as it turned green, well, then, you could cruise on through. I remember that after we had made a few of the lights on green, a hay wagon pulled out in front of us and we hit every red light from then on. When we finally made it through Atlanta, we still had to go to Miami. It’s a long way from Atlanta to Miami.”

The Bluegrass Special! L to R: Monroe, Jim Shumate, “Sringbeans,” Lester Flatt, “Sally Ann” and “Howdy” Forrester. November 28, 1948, en route to show dates in eastern Tennessee. Photo from “Purina’s Grand Ole Opry Souvenir Album” dated 1946. (Original booklet given to this author by banjo scholar Jim Mills.)

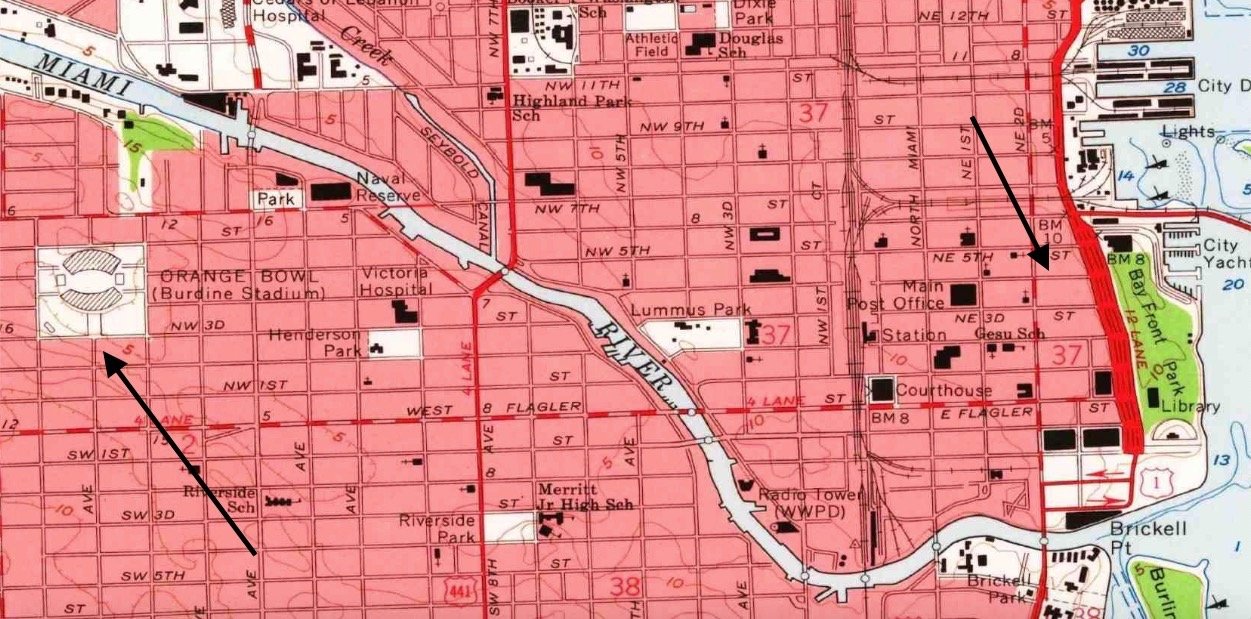

January 1945 must have been just as grueling for the Bluegrass Boys and Girl. After performing on the Opry, they left Nashville at mid-night on the 7th. The first show was at The American Legion Arena in West Palm Beach on the 9th; then, down to the “Orange Bowl” (Burdine Stadium) in Miami for two shows, the 10th and 11th. Somehow, they made it all the way back to Nashville in time for the Opry on Saturday the 13th, after which they turned around and headed back to Florida for the Central High School Auditorium in Fort Lauderdale on the 15th and Vero Beach High School Auditorium on the 19th. Back to Nashville for the Opry on the Saturday the 20th, then back to south Florida for the Grade School Auditorium in Fort Pierce on the 24th, and, yes, back to Nashville in time for the 8pm set on the Opry on the 27th. In fact, the entire year of 1945 was like that, a non-stop, superhuman journey.

Bill Monroe Performances 1945: we can confirm all these dates and personnel based on newspaper ads and first hand accounts. More than likely there were many more.

The Palm Beach Post Tuesday, January 9, 1945.

Who got on board in January of 1945? Fiddler Chubby Wise and bassist Howard Watts (“Cedric Rainwater”), were both from Florida and may have encouraged Bill to expand his range in that state. Dave “Stringbeans” Akemen (later changed to “Stringbean”), from Eastern Kentucky, was Monroe’s first banjo player and had been with him since 1942. Originally from New Mexico, Wilene “Billie” Russell Forrester, whom Bill introduced as “Sally Ann, the Kentucky Songbird,” sang and played accordion all through the war years. (Billie was the wife of champion fiddler Howard “Howdy” Forrester, who left Monroe’s band to join the Navy on March 6, 1943. He endured bitter fighting in the Pacific while serving on the USS Pennsylvania, and was finally discharged on November 21, 1945 after the ship was torpedoed off Okinawa that August. Monroe gave him his job back when he returned). Clyde Moody had been Bill’s duet partner all through the war, and had acquired a good following of his own. But when the recording ban was lifted, Moody made his own deal with Columbia Records and was scheduled to head to Chicago just a few days after the Bluegrass Boys. To fill the significant loss of Moody on guitar and lead vocal, Monroe hired Georgian Tex Willis, who had been recommended by Wise and Watts. Curly Bradshaw joined on second guitar on some numbers and did solo spots with his “mouth harp” in the style of African American harmonica master Deford Bailey. This is the band that Bill would take to Chicago for that first landmark Columbia session, and one imagines musical chemistry congealing on this tour. In addition to the Bluegrass Boys, Zeke Clements was along as well. He shared the bill with Monroe, promoting his new hit, “Smoke On The Water.” “Grand Pappy” George Wilkerson and comedians Jam-Up and Honey added their minstrel antics. Thus, Monroe was able present a full in-person “Grande Ole Opry” experience to audiences throughout the South.

Fort Lauderdale News, Jan, 13, 1945. Note the names of the stars inverted.

In all probability, it happened in Miami. The stars lined up for an immeasurable impact on both Bill Monroe and the F-5 mandolin. On January 10, they arrived at Burdine Stadium, which filled the area between 6th and 3rd Streets in Little Havana just west of the Miami River. The first task was to erect the tent and arrange the bleachers and stage. Light rain commenced that night, and the temperature went down to 43 degrees Fahrenheit. It was a chilly night for folks in Miami, but they must have been snug inside the tent listening to their favorite Opry stars live for the first time. Without doubt, Monroe treated the audience to “Muleskinner Blues” and other powerhouse numbers that had made him a household name. The band was experiencing the excitement of a new configuration with the talented Tex Willis stepping into Clyde Moody’s place. As Moody was on the Opry with Monroe as late as December 2, this was most likely one of Willis’s first tours as a Bluegrass Boy. At some point he introduced a style of rhythm guitar playing that emphasized a strong back-beat. This perfectly complemented Monroe’s fast blues compositions like “Rocky Road Blues.” (Music scholars often cite this sound as an important root of Rock ’N Roll). We have no idea where the travelers found lodging for the night, but late 1940s Bluegrass Boy Jim Eanes told this author “he never saw the inside of a luxury hotel when he was with Monroe.” At best they might have arranged an inexpensive hotel or boarding house in Little Havana, which would have seemed luxurious after surviving on cat naps in the car. The morning of the 11th, they woke to a beautiful January day with a high of 64 that afternoon. If anyone wanted to get out for a walk, that morning or early afternoon would have been the best opportunity. Monroe often mailed correspondence, and the Main Post Office was located on the east side of the river on the block at 1st and 4th Streets. To go there from the stadium area, he would have walked across the bridge at 5th street and then turn down to 4th. There were any number of grand hotels along 4th, 5th and Biscayne: The Alcazar, the Floridian, and at 258 NE 4th Street, the brand new Liberty Hotel, just past the Post Office toward Bay Front Park.

Downtown Miami, ca. 1945. Arrow on left, Burdine Stadium where the concert was held January 10 & 11. Arrow on Right, The location of the Liberty Hotel. Total walking distance from stadium to beachfront, 2 miles.

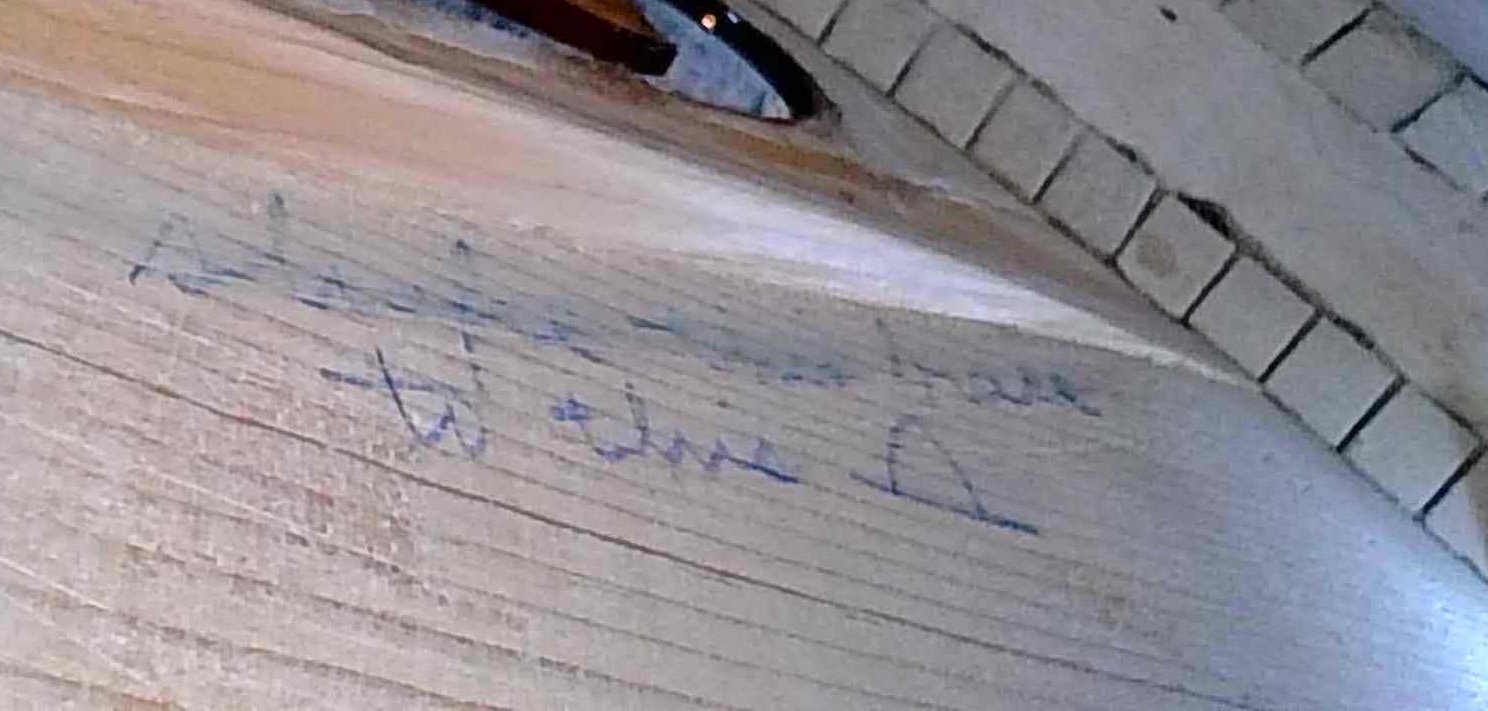

These hotels all featured barber shops with windows to the street. Of course, there were independent barber shops all through Miami in 1945 including Stricklin’s, Sunlight, Star, Stokes’, Rialto, Royal, Rossi, Sam’s, The Seabreeze, and Reagin’s. After researching all of them, we discovered a number of classified ads for high quality musical merchandise, mostly mandolins and accordions, which had been posted in the Miami Herald in 1944 and early 45. All these ads listed the same address: “258 NE 4th Street.” The Liberty Hotel! Each ad used a different name but the same address: “A Mr. M. H. Davis offered a Pietro Accordion for $300”; “Dee” offered an “Italian bass accordion, best offer”; “Fine Gibson Mandolin with a $15 case” no name , just the address; and “Mr. Smith” offered for sale a “Gibson Mandolin, $150 with a leather case.” (In aftermarket ads, the keratol cover of the Geib & Schaefer cases used by Gibson were often mistaken for leather).

Miami Herald, classified ad, 1945. We certainly cannot confirm that this was an F-5 mandolin, but it does confirm that someone was dealing in fine Gibson mandolins and using the address at the Liberty Hotel in 1945.

The Liberty Hotel facing 4th Street, Bay Front Park in the background. (Postcard dated 1945)

The night of January 11, the temperature outside went down to 38 degrees, a record low there for that year. We cannot help but think Bill Monroe heated up that tent at Burdine stadium with Gibson F-5 73987, signed by Lloyd Loar on July 9, 1923, with the black stripes on the side. (Monroe often told the story that he found his F-5 in a “barber shop in Miami”). There is no greater confirmation of the fire that mandolin lit in him than the first recording of “Rocky Road Blues” made in Chicago one month later. The temperature may have hit a record low that night in Florida, but Bill Monroe hit a record high for the century of the F-5 mandolin.

Bill Monroe with Gibson F-5 73987 on stage at the Grande Ole Opry, ca. 1946: This was the most important mandolin of his entire career, and an inseparable icon of his musical identity. (Howard Watts behind with bass)