Gibson F-5 72211 signed by Lloyd Loar on February 26, 1923. The “Tiger” Loar.

Unique, not only for its striking appearance, immaculate condition and crystal clear tone, this 1923 Gibson F-5 mandolin has hidden secrets. Was 72211 on the bench as a pattern in the spring of 1922 when the first F-5s were made? Then, was it assembled later for a very important showcase?

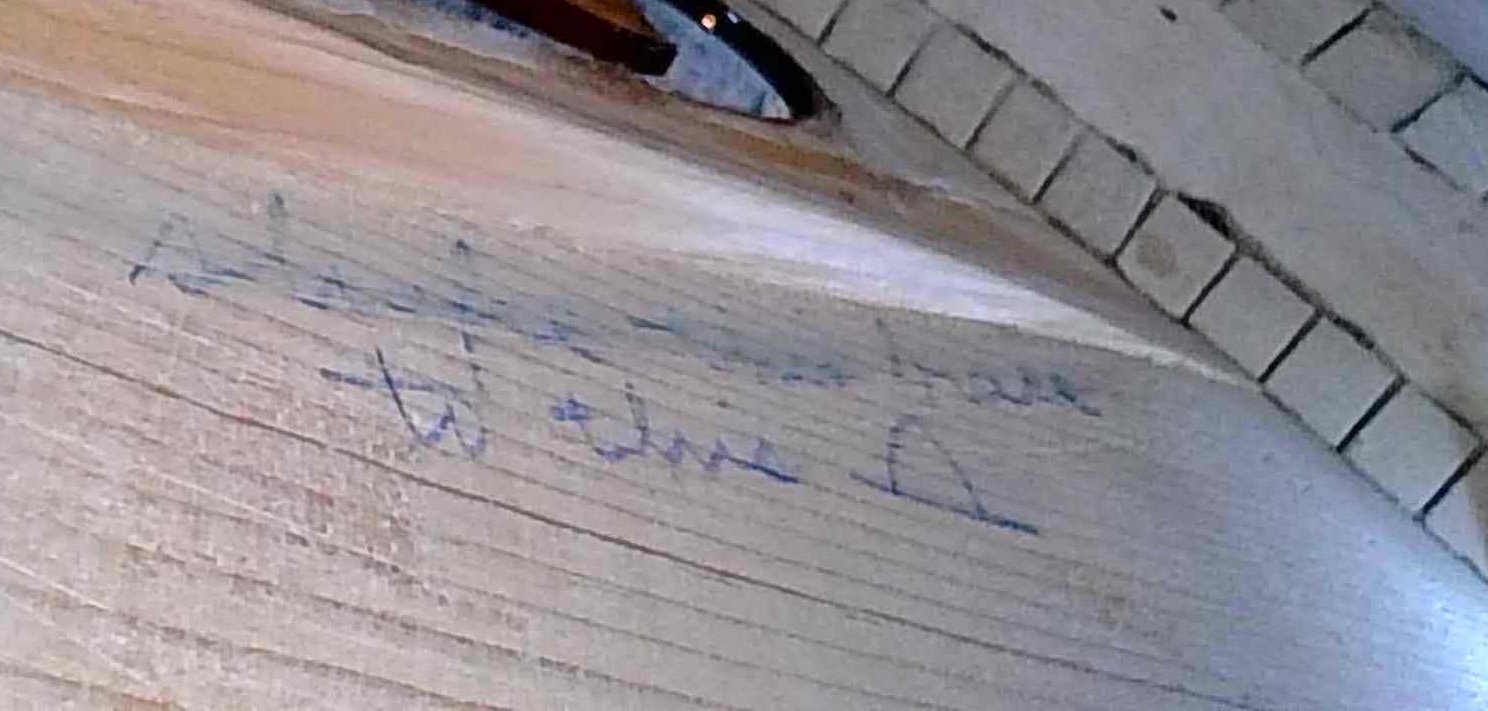

“Shape this brace to this” in blue ink, written in Lloyd Loar’s distinctive cursive by the treble tone bar.

Pencil lines made with a straight-edge outlining the placement of the tone bars,

Curious yellow stains in rather odd places. This one, on the inside of the maple back behind the neck-block.

Altoona Tribune, Altoona, Pennsylvania, February 24, 1923.

On Saturday morning, February 24, 1923, Russell and Riggs Music of Altoona, Pennsylvania, invited customers to come play a “fine new mandolin…with sweet tone of harp,” available at an explosive list price of $200. Gibson planned to unveil the F-5 on April 22, 1923, at the American Guild Convention in Washington D.C., and had coordinated scores of print media ads and articles to be published in March and April. Meanwhile, F-5s were already being delivered to Gibson agents across the country. Russell and Riggs served a hot bed of mandolinists in western Pennsylvania, including some of the first Loar F-5 owners, such as Percy V. Lichtenfels, Paul Weible, Charles Dunford, and Roy Balser Veiock.

Roy Veiock, on left, in the 1914 Gibson catalog “I,” p. 29.

The original owner of 72211 was Roy Balser Veiock, “teacher, soloist, and mandolin orchestra conductor” of New Brighton, Pennsylvania. Such an extraordinarily beautiful mandolin may have been earmarked for the Gibson display at the convention, and Veiock may have purchased it there in 1923. In 1924, he and his students joined the convention orchestra performing H. F. Odell’s “The Crescendo March,” with Mr. Veiock on his beautiful new F-5.

Beaver Falls Tribune, March 24, 1922.

Veiock Music at 507 14th St. in New Brighton was a very successful music merchandiser. Judging by the newspaper ads in the 1920s, much of their commercial focus was on pianos and radios. In an addition to providing Gibson instruments for his students, Veiock had dealerships with the Federal, Steinitz, Atwater and other well-known radio brands, and Starr, Foster Cable, Nelson, Remington, and Colonial pianos. They encouraged their customers to “name your own terms.’

The Evening News, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) · Monday, Apr 16, 1928 Page 12

On April 15, 1928, Roy Veiock was returning home from a visit to his brother’s house when tragedy struck. His death must have devastated his family and the entire mandolin community. The Tiger Loar remained in the case, silent, for many years.

Why “carved like a violin?” Why arch top, f-hole? Since 1064 when William the Troubadour (William IX of Acquitaine) “had brought the song up out of Spain / with the singers and viels” (Ezra Pound, Canto VIII), the mandolin and its ancestors were built with round or oval sound holes, flat or bent tops and bowl backs. After almost 900 years, what inspired such a radical departure from tradition? Why do the names “Cremona” and “Stradivarius” continue to come up when marketing mandolins?

For the answer, we look back another 20 years to find a petite young women with a very big sound and an extraordinary violin.

Marie Hall, at 28, poised to conquer the world of music.

In our opinion, the English violinist, Marie Hall, ignited Cremona fever in the United States in the early decades of the 20th Century. Miss Hall had just turned thirty when she left London for a six-year world tour. She was at the top of her game, having dazzled the classical cognoscenti of Europe since she was a teenager. The American leg of her tour lasted from late 1905 through 1907. She filled every concert hall with brilliant performances and incredible tones on the 1709 Stradivarius violin known as the “Viotti.” Beginning with her debut at Carnegie Hall in New York City on Wednesday, November 5, she blazed a trail of momentous performances, leaving violin fans stunned in her wake.

She arrived in Chicago for a performance on Thanksgiving Day. The Thanksgiving concert was poorly attended, but the few people who were there reported so enthusiastically that on December 2, Orchestra Hall was packed with a standing-room-only crowd. It was a landmark event for Chicago’s music lovers. From there she toured relentlessly across the nation, including many smaller cities in the midwest. In April of 1907, she returned to Chicago for her final midwestern concert on April 4 at Chronicle Hall.

The Inter Ocean, Chicago, Illinois, Nov 26, 1905

Remnant from the program at the Chicago concert, November 25, 1906.

Off to San Francisco by train, then ship to Australia, the Pacific Islands (where she worried incessantly about the distress of the humidity on her violin) and finally, South Africa in 1910, where she earned £10,000, reportedly the highest fee ever paid a violinist for a single tour.

Often her diminutive size caused reviewers to refer to her as frail, and point out the contrast between her appearance and the majesty of the sounds coming from the violin. Everywhere her performance was praised and it was almost always pointed out that the sound of her violin was “magnificent,” “heard in every seat, even in the back of the third balcony.”

What does Marie Hall and the “Viotti” Stradivarius violin have to do with Lloyd Loar and the F-5?

On December 18, 1905, Lloyd Loar’s younger brother Jonathan died at the Loar family home in Lewiston, Illinois. Lloyd left college and went to be with his family during this tragic time. Oberlin records show that he did not graduate in the spring of 1906 with the rest of his class, nor is there any indication he came back to school after New Year’s Day, 1906. By the spring of 1906, he was on tour full time with the Fisher Shipp Concert Company.

At the same time as the passing of the 17-year-old Jonathan Loar, in late December of 1905, Miss Fisher Shipp of Brookfield, Missouri, was absent from a number of engagements with the Oilenbein Male Quartet with whom she had appeared throughout the mid-west for the previous three years. She was already a regional star, and well known in Missouri society. By early 1906 Miss Shipp had signed with the Columbia Concert Company in Chicago, and had invited Lloyd Loar, mandola, and Freda Bethig, violin, to join her as they performed in many of the same towns and venues as Marie Hall.

In 1905, Victor Kraske was in Chicago building banjos and mandolins under his own name, and was associated with Orville Gibson. In 1906 Kraske left Chicago to work for Gibson in Kalamazoo when the first f-hole Gibson Artist Mandolin was built (See Shape Brace to This, Episode 4). What inspired him to put f-holes in one of Orville Gibson’s designs?

In a departure from our preferred adherence to primary source information, we cannot resist the following conjectures.

Were Victor Kraske and Lloyd Loar—and perhaps even Orville Gibson— in the audience when Miss Hall took the stage in Chicago in 1905? Were they stunned with the power, tone and projection of the instrument? Did they meet her backstage for a chance to inspect the “Viotti” Stradivarius? Did this amazing instrument and brilliant young virtuosa inspire Loar to embark on a twenty-year journey to excel as musician and create a better mandolin as acoustical engineer?

Now, consider Mrs. Andersons’ dinner party. At 10:30 pm. on February 5, 1906, thirty guests were treated to a private house concert by none other than Marie Hall. The hostess was Mrs. Ardell Anderson of Kansas City, Missouri, and her guest list included the crême de la crême of society. At midnight, they all dined in the grandest style. Shipp had already performed for President Roosevelt and had tremendous social standing in Missouri. This was a short distance from Miss Shipp’s home, where her 1906 concert group were most likely already rehearsing. Was Fisher Shipp one of the guests at Mrs. Anderson’s party? Were Lloyd Loar and Freda Bethig there?

The Kansas City Star and The Kansas City Times (Kansas City, Missouri) ·Feb 6, 1906, Page 12

L to R: Lloyd Loar, Fisher Shipp, Francis “Mamie” Allen and Freda Bethig. Were they inspired by Marie Hall?

Whether this thesis is a revelation, or the product of imagination run wild, in the wake of Marie Hall the word “Cremona” became a buzz word for music in America that Gibson continued to apply to mandolins over the next century. And while a study of violins like the Viotti Stradivarius may have been a jumping off place, the Tiger Loar represents the culmination of a vision twenty years in the making.

The Viotti-Hall Stradivarius.

Gibson F-5 72211, February 26, 1923.