The initial flier advertising the Gibson model F-5 mandolin, “The Master Model,” appeared in March of 1923. (high quality reproduction courtesy Tom Isenhour)

The March 1923 issue of the Cadenza magazine opened at the center to a two-page advertisement entitled “Again The World Hears A New Tone.” With that, the campaign to market the new Master Model mandolin officially began. With typical Gibson hyperbole, the F-5 was proclaimed the most important innovation in the mandolin world since Orville Gibson carved the first mandolin soundboard.

Cadenza Vol. XXX, #3, March 1923, center pages, 16-17.

The first Master Models appeared in 1922. It had been a long time coming, the result of a team of talented people infused with the work ethic that was often a hallmark of that era. Lloyd Loar had brought ideas and innovation as well as aggressive supervision and a demand for perfection; Lewis Williams, General Manager and founding member of Gibson Mandolin and Guitar Company, supported such innovation and was an inventor himself; in the factory, the foreman Victor Kraske had already put a violin-type f-hole into a Gibson mandolin almost twenty years earlier and we suspect he may have been a key element in the creation of the new mandolin. Superb craftsmen, many of them immigrants, commanded space at the workbenches: Hans Larsen, Adrian Glerum, John Patterson, John Voisine, and George Altermatt to name a few; Ted McHugh had moved from his position as foreman to construction engineer; Henry T. Reeves, draftsman, worked alongside McHugh; machine operator Joseph P. Curtiss may have played a key role; and Fred Miller and Cornelius Kivet, former painters in the automotive industry, created the “Gibson Cremona” varnish finish. (For a more complete list of woodworkers, machinist, draftsmen, finishers and inventors who worked for Gibson during the Loar Era, see “Breaking News 1922, April 5, 1922, ‘Shape Brace To This.’”) In the office, stenographer/musicians such as Dorothy Campbell and Nell VerCies helped design and reproduce advertisements, such as the one above, and kept up the correspondence with the teacher/agents across the country. (By night, these multi-talented young women performed on Gibson instruments in the all-girl orchestra, “The Gibson, Melody Maids.”) In a final operation unique in the annals of music manufacturing, The Gibsonians, professional musicians led by Lloyd Loar and including such brilliant instrumentalists as Walter Kaye Bauer, carried the first of these new instruments throughout the mid-west and Canada, playing over 100 engagements, testing, trying and approving them under the most extreme conditions. (See Breaking News 1922, August 4, 1922, “On The Road”) The Master Model was now ready for “the world to hear.”

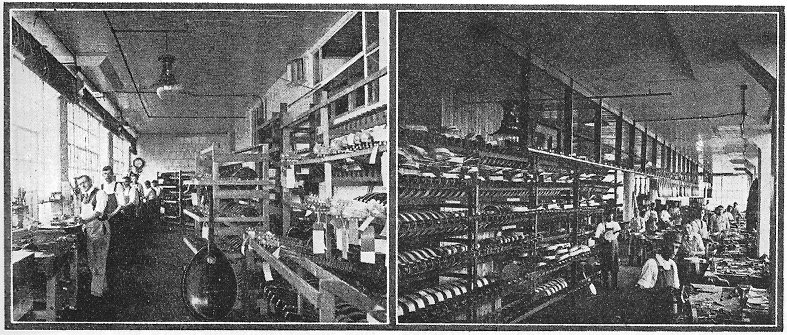

Gibson factory as it appeared when Lloyd Loar first moved to Kalamazoo. Left, the stringing department, James P. Johnstone (with glasses) foreman; Right, one section of the woodworking department. Gibson Catalog “M” 1921.

In March of 1923, what was the world actually hearing? Gibson had high hopes that at the upcoming Guild Convention in April the mandolin world would be dazzled by the qualities of the new instruments. However, at around the same time Gibson was turning out the first batches of new mandolins, a 22-year-old African-American musician from New Orleans got off the train in Chicago. His name was Louis Armstrong. He had arrived at the invitation of his longtime idol and mentor, Joe Oliver, to join “King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band.” From across the midwest and beyond, music fans, both black and white, overflowed Chicago’s Lincoln Gardens to hear them every night. Their first recording session, scheduled for April 5, 1923, showcased their brilliant new star, and knocked the world of music on its ear. Armstrong had begun a career that would lift jazz out of the dins of iniquity and transform it into a truly American an art form.

Left to Right: Honore Dutrey, trombone; “Baby” Dodds, drums; King Oliver, trumpet; Louis Armstrong (kneeling), trombone and trumpet; Lil’ Hardin, piano; Bill Johnson, banjo; Johnny Dodds, clarinet. (Photo: , Jazz Archive)

“Moral disaster is coming to hundreds of young American girls through the pathological, nerve-irritating, sex-exciting music of jazz, according to the Illinois Vigilance Association. In Chicago alone, the association representatives have traced the fall of one thousand girls in the last two years to jazz music.” New York American, January, 1921.

Young ladies performed the “Charleston” dance to Jazz music and adopted short haircuts and hem lines that ended well above the ankle.

By March of 1923, the jazz age was in full swing. Prohibition had resulted in an opposite effect than intended. Alcohol consumption skyrocketed. In New York City alone, where, in 1918, there were only a few neighborhood pubs, there were now over 5000 speakeasies. A multi-million dollar illegal industry—controlled by mobsters—sprang up overnight. Every speakeasy boasted a raucous scene and equally raucous music. Young people flocked to the joints to enjoy the frenzied new dances and all-night revelries. Young women sported short hair and what for those times were considered shockingly short hem-lines. Some even formed all-girl jazz bands and played the new music to packed houses.

The Ingenues, circa 1925. These young women were a sensation as they toured the US from their home base in Chicago.

What did this mean for the professional mandolin player? The traditionalists continued playing the music as before, which was based on European tradition. Many agreed with the Illinois Vigilance Association, expressing rage at the loss of moral integrity and predicted a quick demise for the “noise” called jazz and a tragic end to those who participated in the primitive gyrations. Virtuosi like Samuel Segal and Giuseppe Pettine found audiences in Europe more receptive to their performances.

On the other hand, for many musicians, the situation created unprecedented opportunities for employment for those willing to take a walk on the wild side. Of course, this meant embracing the new sounds, and learning to play them, and in many cases, for the sake of volume, switching from mandolin to the tenor banjo, or mandolin banjo. Gibson stalwart, James P. Johnstone, was an early proponent of the new sounds and sought to bring other plectrum players along, finding a place for it in the existing system of mandolin clubs. His emphasis on banjo music and rhythm earned him the nickname, “Jumping Jazz Johnstone.” In an article for the Crescendo, Johnstone explains: “Jazz playing is nothing more or less than ragtime or syncopation only in a more intensified form. The various styles of syncopation are learned and then applied to any given melody. The book that I have written and published is, I believe, the only book of its type entirely devoted to jazz playing, and I’ve tried to illustrate, as far as can be done with printers ink, all the styles of syncopation and their method of application. The article covers the subject more or less without the aid of printed music. Jazz playing after all, is just stuttering, and the more you can stutter over a melody the more you were jazzing it. Foxtrots in 4/4 time are best adapted to jazz playing as there are more whole and half notes to stutter over.” James P. Johnstone, Crescendo, July 1920.

James “Jazz” Johnstone, on right, and Wyatt W. Berry, “stuttering” with banjos at the Gibson factory. The Gibson banjo had found a place for novelty tunes in mandolin clubs, but at this point, all the commercial jazz players preferred other brands. Those with lucrative earnings were often seen with Paramount banjos.

Lloyd Loar took a broader view. In a lengthy article entitled “Is Jazz Constructive or Destructive” in “Melody Magazine,” he defended both camps equally and with prophetic insight, proposed a musical synthesis—a melting pot—that would eventually contribute to the development of a unique and truly American music that would have a place for all instruments, including the mandolin, and especially the F-5.

“While Jazz is a rather indefinite term, we might say it is a more highly seasoned dish than the one we were fed a few years ago. The extra seasoning may consist of more intricate or insistent rhythms, dashes of more brilliant tone color, or greater variety of harmonic material. The constructive effect jazz has had on popular music is decidedly noticeable. The improvement will continue; good taste and a liking for beauty will keep on working their constructive changes and the first thing we know we will have a national music liked and understood by all of us!”—Lloyd Loar, Melody Magazine, June, 1924, “Is Jazz Constructive or Destructive?”

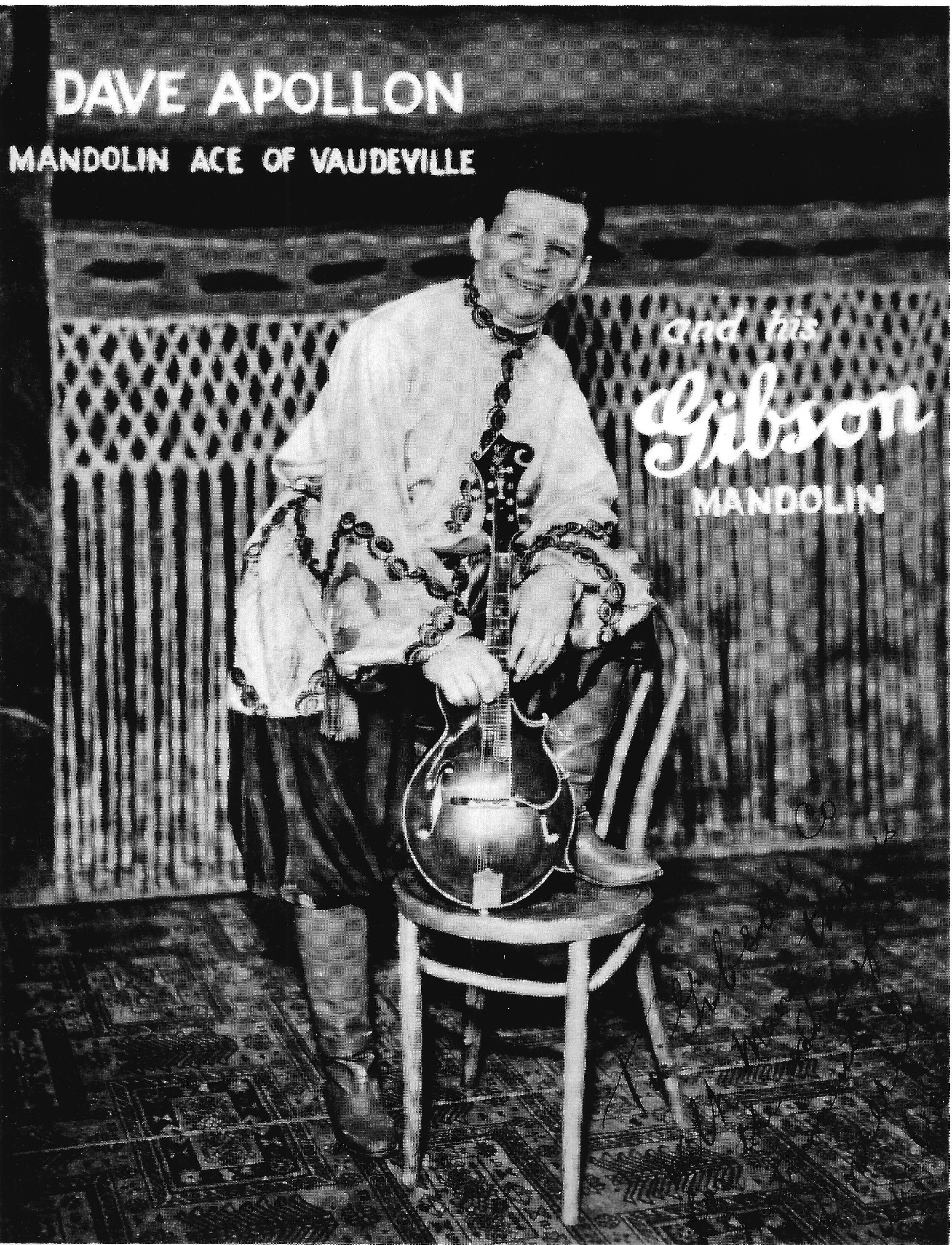

The one person who understood the entertainment potential of the new music and the place the F5 would fit into it was Dave Apollon.

Quad City Times, Davenport, Iowa, Sunday, May 10, 1936,

The Dayton Herald, Nov 9, 1935.

On December 3, 1928, the headline of the Indianapolis Times read: “Hot Jazz Music is Big Indiana Hit.” The article refers to an appearance by none other than “Dave Apollon and his string orchestra with his Broadway Review.” Apollon realized the F5 was an instrument that could fulfill the needs of the modern player and be heard even above jazz rhythms. His lavish production included dazzling instrumentals and vocals and young women dancing the new dances while sporting short haircuts and even shorter outfits. Apollon understood that if he were to maintain his stardom, he must give jazz fans of the prohibition era the show of a lifetime. The difference of course, was that instead of cornets and saxophones, the girls danced to mandolin music!

Dave Apollon with Gibson F-5, most likely #73009, signed April 25, 1923. Inscription reads “To Gibson Co. many thanks for the wonderful instrument. Sincerely, Dave Apollon.” (photo courtesy Tom Isenhour)