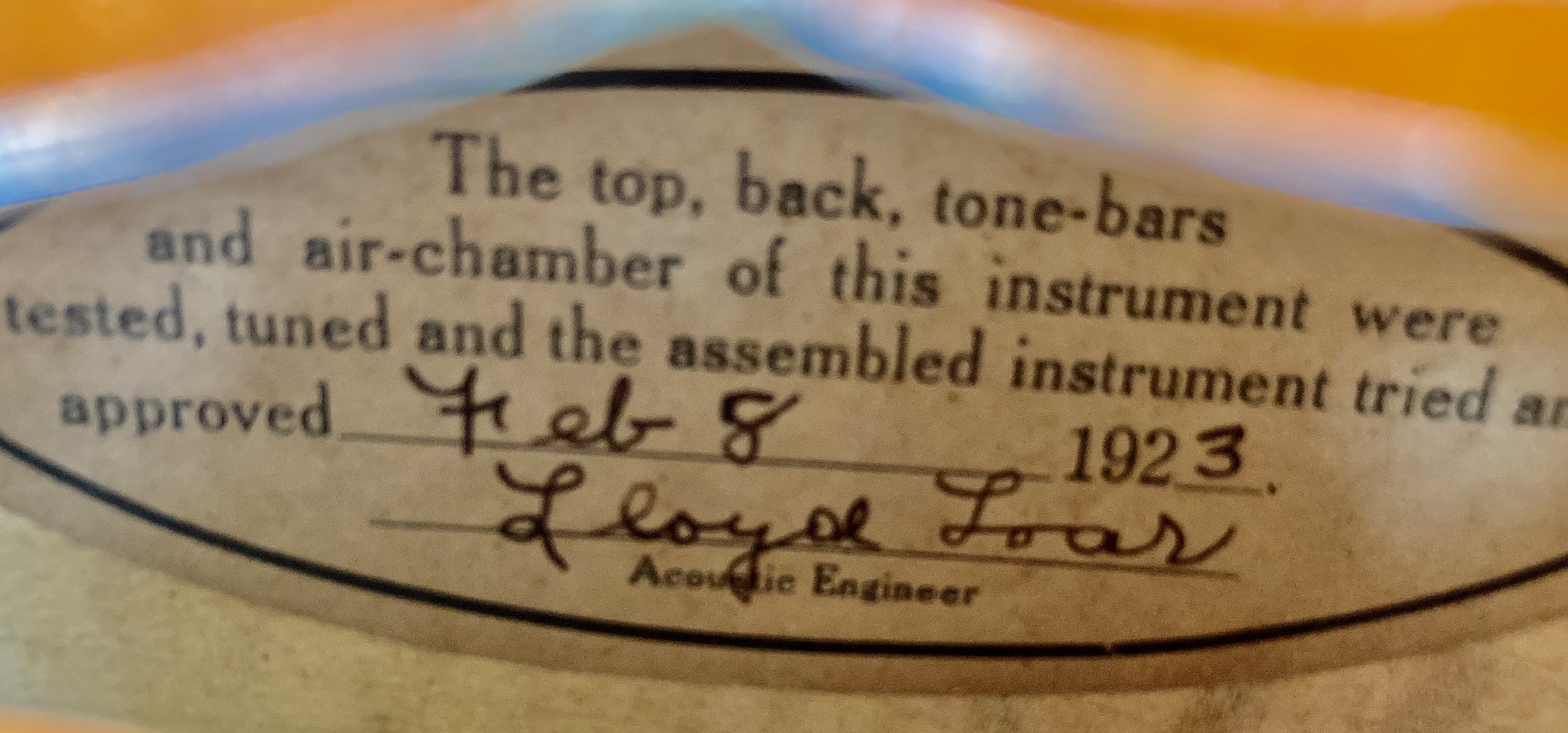

“The Gibson” F-5 72060, signed by Lloyd Loar, February 8, 1923, .

“The Crescendo,” Vol. XV, #8, February, 1923, p. 19.

The February 1923 Crescendo magazine, which was mailed from Boston on January 27, contained a mysterious, auspicious announcement promising a “most momentous development.” By the time the magazine arrived in Kalamazoo, Michigan, on February 8, Lloyd Loar was putting his signature, with his unique flourish of the fountain pen, to another batch of labels to be affixed into finished F-5 mandolins. His signature, in his capacity as “acoustic engineer,” had already appeared on June 1, November 28 and December 20 in 1922, and January 5 and 12 in 1923.

The maiden voyage of the F-5 during the summer of 1922 had been a big success. Lloyd Loar and his “Gibsonian Orchestra” had showcased the new designs in mandolin and banjo family instruments, playing Loar’s own compositions and arrangements. At over one hundred venues in midwestern United States and Canada, the initial response had been tremendous. The Gibson Mandolin Company of Kalamazoo, Michigan, had every reason to expect a huge demand for the new instruments.

Many modern writers have concluded that the mandolin orchestra movement was extinct by the 1920s. Many young music lovers and dancers had embraced the new sounds and rhythms, and the banjo had grown significantly in popularity. However, in the December issue of the Cadenza, Walter Kaye Bauer, who had performed with The Gibsonian Orchestra in 1922, published a list of well over a hundred mandolin ensembles still very much alive in February of 1923. Many incorporated the banjo alongside the mandolin with a variety of repertoire. While not all these ensembles were “Gibsonites,” most of the F-5s known to have been sold between 1923 and 1927 were in the hands of players in one or another of these ensembles. In some instances, popular big band leaders appropriated F-5s for multi-instrumentalists to add color to appropriate selections.

In the same article, Bauer listed active small ensembles (see below). Nearly all these groups had at least one F-5 mandolin by 1927. Some even featured the H-5 mandola and a few had a K-5 mando-cello.

“The Cadenza,” Vol. XXIX #12, December 1922, pps. 35-37.

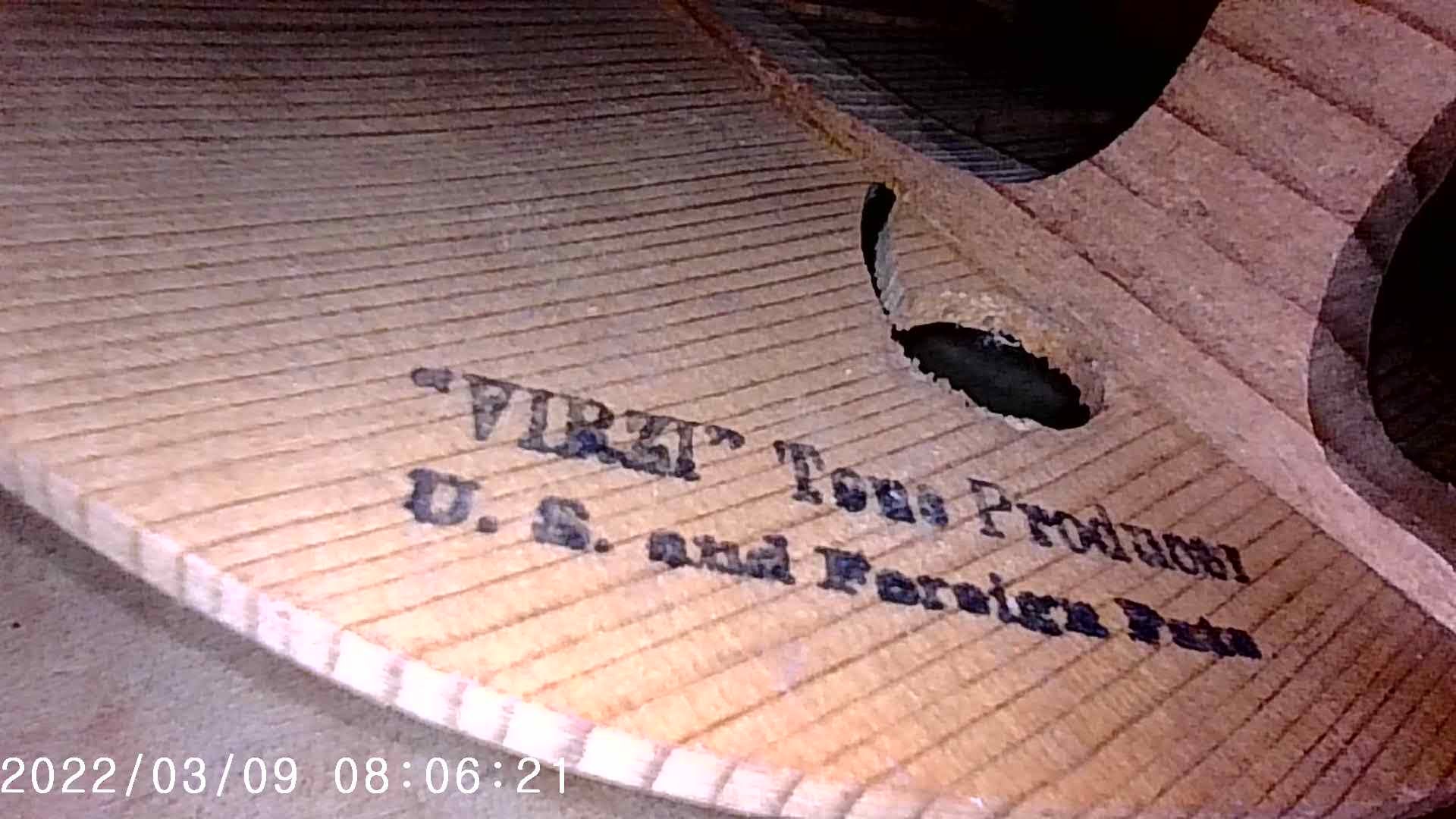

In addition to the f-hole, carved-top design and the “Gibson Cremona” finish that were the hallmarks of the F-5, a unique innovation appeared early in 1923 and became almost standard issue by 1924: The Virzi Tone Producer.

The “Virzi Tone Producer” from Feb 8, 1923 F-5 72060, one of the first mandolins to receive the Virzi Tone Producer at the time of manufacture. Photographed in situ, exactly as it was installed in 1923.

Violin makers Giuseppe and Giovanni Virzi from St. Agata, Messina, Sicily, learned their craft in the shop of their father, Rosario Virzi, master wood carver, cabinet maker and musical instrument maker. Younger brother Giovanni, who had made and played violins and mandolins in Sicily, arrived in New York City on May 4, 1907, and, according to immigration records, Giuseppe and his family were already settled there. On March 25, 1914, after a wood-buying trip to Italy, Giuseppe returned to New York on the ship “Hamburg.” At that point, the brothers began working in earnest at their workshop at 503 Fifth Avenue. They became celebrated for their high-quality violins modeled after a Stradivarius loaned to them by a “Mr. Betti.” They used old Italian wood exclusively and made an oil varnish of their own formula in either golden yellow or reddish yellow color. On July 30, 1920, the News Journal of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, was first to announce the invention of a secondary vibrating surface to be suspended inside a violin top, which created a “striking quality of sound” even when installed in “ordinary, inexpensive instruments.” A US patent for a “Tone Amplifier for Stringed Instruments, Giuseppe Virzi, inventor,” was applied for October 21, 1920, and granted April 11, 1923. It is unclear exactly when Lloyd Loar became interested in their work, but by 1922 he was experimenting with the device in mandolin family instruments. It seems possible that, like so many of the outsourced appointments of Gibson instruments, that the actual “Amplifier” for mandolin that Gibson used may have been made at the Virzi shop in New York and shipped to Kalamazoo complete with label with serial number and Virzi logo. In addition to installing the device in new mandolins, Gibson created a revolving door approach, installing and/or removing the Virzi in existing mandolins at a charge of $15 for each operation. Many instruments from this period on through the 1930s show evidence of having had the back sawn off to facilitate this procedure. In 1923, a “Gibson” violin was marketed. Except for “The Gibson” label, it is our understanding that it was an instrument built by the Virzi Brothers in New York. Gibson’s relationship with Virzi continued through 1927, three years after Loar had left the company to work in publishing in Boston.

In 1923, the outside tip of the foot of the Virzi was removed to fit against the tone bar. The contacting surfaces of the foot were glued to the underside of the spruce top and the tone bar with hide glue.

Virzi Tone Producer removed from February 18, 1924 F-5. Note the outside tip of the feet has only a slight notch, quite different from the foot on the installation in the 1923 mandolin. By 1924, the position of the braces had been widened to accommodate the Virzi attachment. Some later models also had a small brad securing one of the feet to the top,

Below, Lloyd Loar’s first article on the Virzi Tone Producer, published in the Music Trade Review, December 16, 1922.

Music Trade Review, December 16, 1922.

Music Trade Review, December 16, 1922 (continued from above).

While Loar describes the effects of the Virzi in his characteristic technical language, the modern audience may want to approach this as a subjective phenomena. In our experience, we have noticed that many Virzi mandolins have remarkable projection, and a sustain that seems to amplify the tremolo. While many players report a reduction in volume, in most cases, there is an opposite assessment by those listening at a distance. This effect is most profound when played acoustically in a concert hall with excellent acoustics.

The February 1923 edition of the Crescendo Magazine had another headline of great interest to the mandolinist: “Are you making arrangements to attend the Guild convention at Washington on April 22? As announced last month, there will be two concerts. The official hotel with be the Raleigh hotel at 12th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue. Engage rooms ahead in order to secure proper accommodations.” Suffice it to say, big plans were being made in Kalamazoo, and the spring of 1923 will be the public unveiling of “the most momentous development!