Factory Order Number 11940 found under the label on F-5 75690. Photo by John Monteleone, courtesy Mike Marshall.

Did the woodworkers who stamped 11940 and 11965 on the inside of sugar maple mandolin backs in late October of 1923 feel a tingle of excitement? Was there a glimpse of the tone colors that would ripen throughout the next century? Did they dream that these mandolins would one day be some of the most listened to, most lauded group of F-5s of all? In the hands of Mike Marshall, Chris Thile, John Paul Jones, John Reischman, Gene Johnson, Andrew Marlin, and many others, the February 18, 1924, F-5s have become the icons of a generation of mandolinists. Of course, this was the signature date on Lloyd Loar’s personal F-5. The story of those mandolins began with that stamp, one hundred years ago in the autumn of 1923. But while magic was being created in the wood shop, upstairs, a dark future for the F-5 was unfolding.

Gibson F-5 #75309 signed by Lloyd Loar February 18, 1924. According to the FONs known, this batch was most likely stamped in October or November of 1923. This batch is famous for the rich, dark sound.

What actually happened? Again, we are looking “through the glass darkly,” due to the lack of accurate records extant, and the primary source materials are as obscure as they are diverse. Also, none of the distinguished modern authors on the subject agrees on how events unfolded. After exhaustive search through various city directories, articles in Music Reports, Cadenza and Crescendo Magazines and many, many newspapers articles, we offer this report.

There were many factors at play on the world stage. The nation was still reeling from the pandemic of 1917-1918; the deflationary recession of 1920-1922 contributed to record unemployment; during World War I immigrants had flooded into Ellis Island and at the end of the war soldiers returned expecting their old jobs back; united workers’ unions threatened shutdowns and even riot; Prohibition continued to have a negative financial impact on legal establishments; organized crime in the North and the Ku Klux Klan in the south nurtured fear; easy access to new types of music by radio and phonograph recordings led to changes in musical taste, especially for a younger generation; and, innovations from Vega, Paramount, Washburn (formerly Lyon and Healy) and other musical instrument manufacturers offered stiff competition. All these factors led to red ink in the ledgers at Gibson.

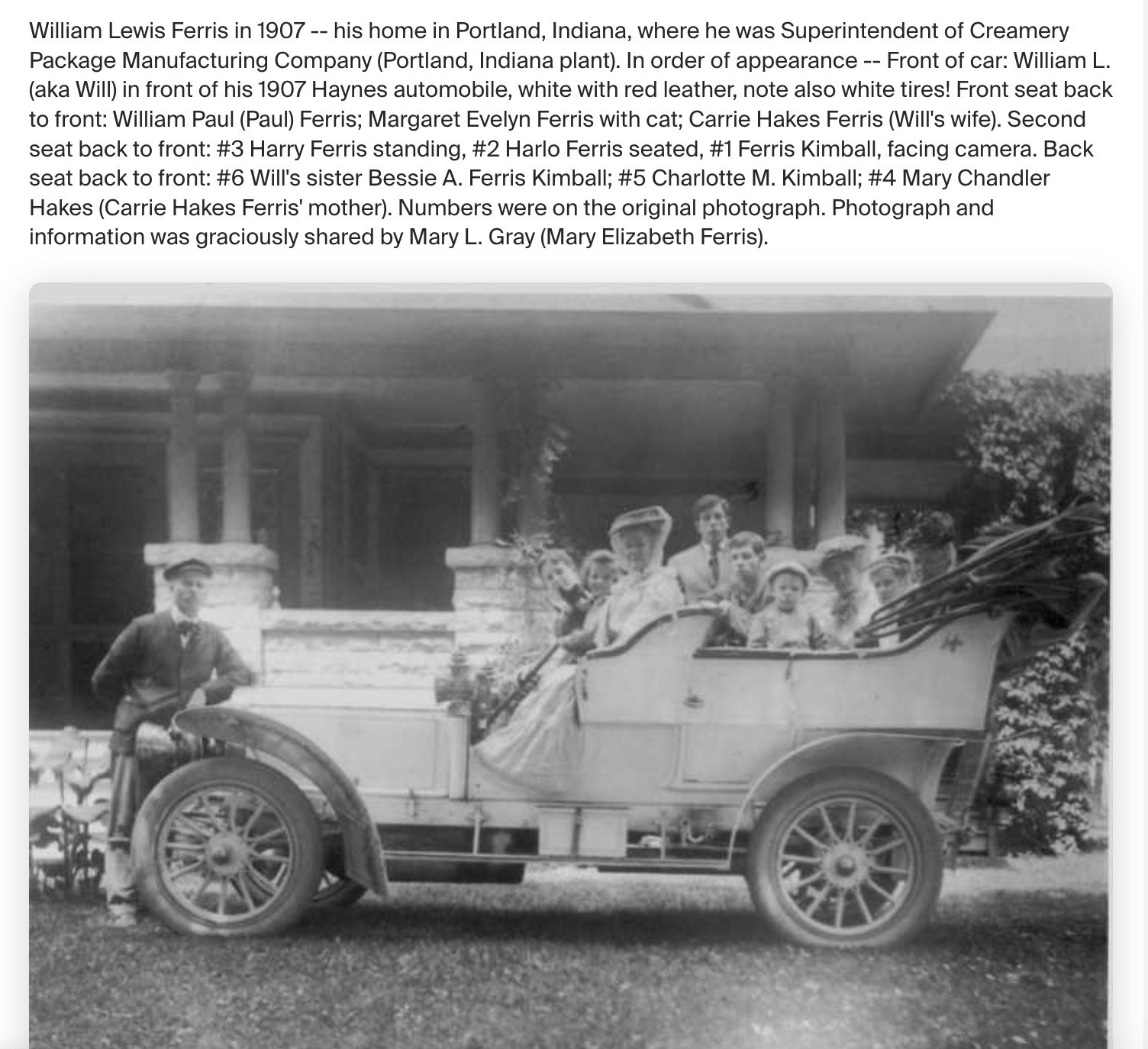

In the autumn of 1923, in the most dramatic shake-up since they sent Orville home in 1906, the Board of Directors under the leadership of Judge John W. Adams hired Harry L. Ferris from Waukesha, Wisconsin, as “Secretary and General Manager,” and they changed the title of the corporation to “Gibson, Inc.,” dropping the words “Mandolin and Guitar.” In what some employees may have viewed as a painful stroke, they asked for the resignation of former General Manager and founding member Lewis A. Williams. In an extremely curious redundancy, Clifford V. Buttelman, formerly the advertising manager, was also given the title “General Manager.” Coinciding with this move, Lloyd Loar’s title was increased from “Acoustical Engineer” to “Superintendent and Acoustical Engineer” and sales and advertisement responsibilities were added to his role. Also, around the same time, they hired Guy Hart as accountant (a man who would figure prominently in the post-Loar era). (All these events are documented in articles in Music Trade Review except we do not have confirmation of the exact date of Ferris’ hiring, but the 1924 Kalamazoo City Directory, compiled at the end of 1923, lists him as resident and lists both Buttelman and Ferris as “Genl Mgr”)

Harry Lewis Ferris, around the time he came to Kalamazoo.

Harry Lewis Ferris left his vice-presidency at Waukesha Manufacturing Company, where his father was president, to come to Gibson. The Ferris family was well off, as patriarch William Ferris had flourished in manufacturing food products and cookware, and had groomed his son to follow his footsteps. It is unclear why the younger Ferris left the family business in 1923, but he returned there immediately after his year at Gibson ended. He was the first General Manager at Gibson who was not a musician. At Oberlin College, where he majored in Sociology, his only musical endeavor was as a member of the choir. Some writers point out that Loar and Ferris shared the same Alma Mater, and that Loar must have suggested Ferris for Gibson. Loar matriculated into Oberlin in 1903 and left at the end of 1905 to become a full-time musician; Ferris was in school there from 1912 to 1915, and upon graduation took an executive position in his father’s business. Most certainly Loar and Ferris were not classmates, and there is no evidence showing that the two had ever met before October of 1923.

Harry Lewis Ferris, Oberlin College yearbook, 1915.

Ferris has been lauded as “the man who saved Gibson.” Of course, the evidence that Gibson was in debt at the beginning of 1923 and was turning a profit during the Ferris reign supports the idea that hiring Ferris was an economically sound move. During the recession of 1920-1922, Gibson under Lewis Williams and Lloyd Loar poured energy and money into innovation rather than struggle with a depressed market. The fruits of their labors, like the luxury-priced F-5 mandolin, left the factory in surprising numbers in 1923. But those sales were either to artists, teachers or players, most of whom took advantage of payment plans. The actual remuneration for these innovations trickled in over time, and it wasn’t until 1924 that the project began to show profit. At that point, Ferris took all the the credit for the increase in solvency.

What did Mr. Ferris actually do? He went on a cost cutting rampage, with the costliest project, the F-5, firmly in his cross-hairs. During October and November of 1923, large batches of mandolins that were signed in 1924 were being stamped. Under Ferris, discrimination toward choosing only the best materials for the F-5 seems to have been compromised. For example, in the ’24 mandolins, we occasionally find spruce tops not book-matched; mildly figured and even slab-cut backs; and orphan parts from discontinued ideas, like 3-piece necks and bodies with side-bindings. The amount paid to Geib and Schaefer for the “Faultless 440 SP” F-5 case was reduced by discontinuing the emerald green silk-plush lining (SP) and returning to the red velour of the pre-Loar era. The cost of the case to consumers remained the same. Projects that may have been on the table for development, like the A-5 mandolin and the 10-string mandolin-viola, were scrapped. Lewis Williams, whose early interest in electronics is documented in this journal, may have teamed up with Lloyd Loar to broach the idea of electric instruments, but Ferris would have none of that. The H-5 mandola and the K-5 mandocello were relegated to limited production. Fern inlays, originally earmarked for H-5s, were put into F-5s. The K-5 mandocello became a guitar. Ivoroid binding was replaced with plain white plastic. Virzi-tone producers already in stock were put into mandolins without waiting for a custom order.

Gibson F-5 from the February 18, 1924 batch with mismatched top.

Gibson F-5 from the February 18, 1924 batch with 3-piece neck and side binding, both features from previous batches. (Photo courtesy Steve Gilchrist)

What may have been seen by the craftsmen at Gibson as a crippling strategy was instead a challenge to continue the commitment to excellence. They succeeded brilliantly. A darker shade of sunburst covered any imperfections in the wood and by late March they began scraping the finish off the white binding to create an elegant contrast. Of course, they continued to tune the instruments for tone and projection, and for whatever reason, the mandolins sound darker, moodier, what some call “chocolaty.” In fact, many feel that these are some of the best sounding F-5s of the entire Loar era!

Ferris’ mandate for efficiency, to put every scrap of wood into production and re-use parts from instruments not approved, helped create the largest batches of F-5s yet. Consequently, Gibson flooded the market with F-5s in 1924. At the same time, all mention of the F-5 or the Master Models was removed from Gibson advertising in the Crescendo and Cadenza, and no ads at all were placed in Music Reports or other magazines. Not surprisingly, many of these F-5s did not find buyers until 1926. Could it be that Ferris was not the man who saved Gibson, but the man who scuttled the Master Model Project? In short, he was the man who chose immediate profit over a legacy of excellence, and curtailed the possibilities for the long-term future of consistency, elegance and mastery that the team under Loar may have created.

Gibson F-5 75696, signed February 18, 1924, considered to be one of the best sounding F-5 mandolins, can be heard on selected recordings by Tony Williamson and is currently on tour with Andrew Marlin of “Mighty Poplar.”

During his year at Gibson, Ferris made an effort to discontinue, or at least greatly restrict, the artist/teacher program that had been the sales model since the days of Orville Gibson. In its place, he facilitated accounts with larger music stores and chains. Of course, under Buttelman and Williams, Gibson already had a relationship with such stores as the Grinnell Brothers in Detroit, Lyon and Healy in St. Louis and Jenkins Music in Kansas, City. These were indeed large operations with satellite stores, but also ones where the Gibsonians and Gibson Melody Maids were welcome to give concerts and demonstrations which drew musicians and teachers from the mandolin clubs and schools in the area. Ferris expanded to large stores that had previously focused on piano, band or orchestra instruments. However, none of these stores was particularly interested in mandolins, so Gibson began putting banjos on display.

Conn of Chicago announces acquisition of the Gibson line of instruments in the Music Trade Review, July 5, 1924.

In late 1924, Ferris began streamlining the employee roster. In doing so, he dismissed or gave notice to many workers who we think may have played key roles in building the F-5s, including woodcarvers John Patterson and John Voisine; woodworker Adrian Glerum (who was rehired to head the violin department in the 1930s); and draftsmen Henry T. Reeves and Francis Havens. Ferris realized the time and cost-saving advantages of using the new nitrocellulose lacquer finish which had been invented by DuPont employee Edmund Flaherty in 1921. In 1923, by using this new finish, General Motors had increased production and cut costs to create a more affordable automobile. Ferris took note. Nitrocellulose lacquer was inexpensive, could be sprayed on and would dry quickly. The “Two Gentlemen of Cremona,” Fred Miller and Cornelius Kievit, who created the “Gibson Cremona Brown” which employed a unique synthetic varnish finish, were dismissed. By 1925, Gibson would never again apply that finish, which was crucial for the look and sound of the Lloyd Loar F-5. And of course, most disastrous of all, Ferris’ insistence on high production and low cost instead of experimentation and innovation eventually made work at Gibson virtually unbearable for Lloyd Loar himself.

Lewis Williams had been an active player in the development of the Master Model project, and a staunch supporter of Loar’s work there. One cannot help but imagine his disappointment in his sudden departure from Gibson. Williams explained his departure in a letter published in both the Cadenza, (November 1923) and the Crescendo (December, 1923). We cannot help but sense the emotional component for Williams and his friends and supporters.

Williams had already established “Specialize Radio” at 718 West Kalamazoo Avenue, and had addressed a meeting at the Guild Convention advocating radio as a “furtherance for fretted instruments.” Spending nights in his shop creating custom amplifiers for radio, he must have considered applying this technology to fretted instruments. After leaving Gibson, he threw himself full-time in this work, and in 1933, attracted Lloyd Loar into a partnership to design, build and market electric instruments under the brand “Vivi-Tone.”

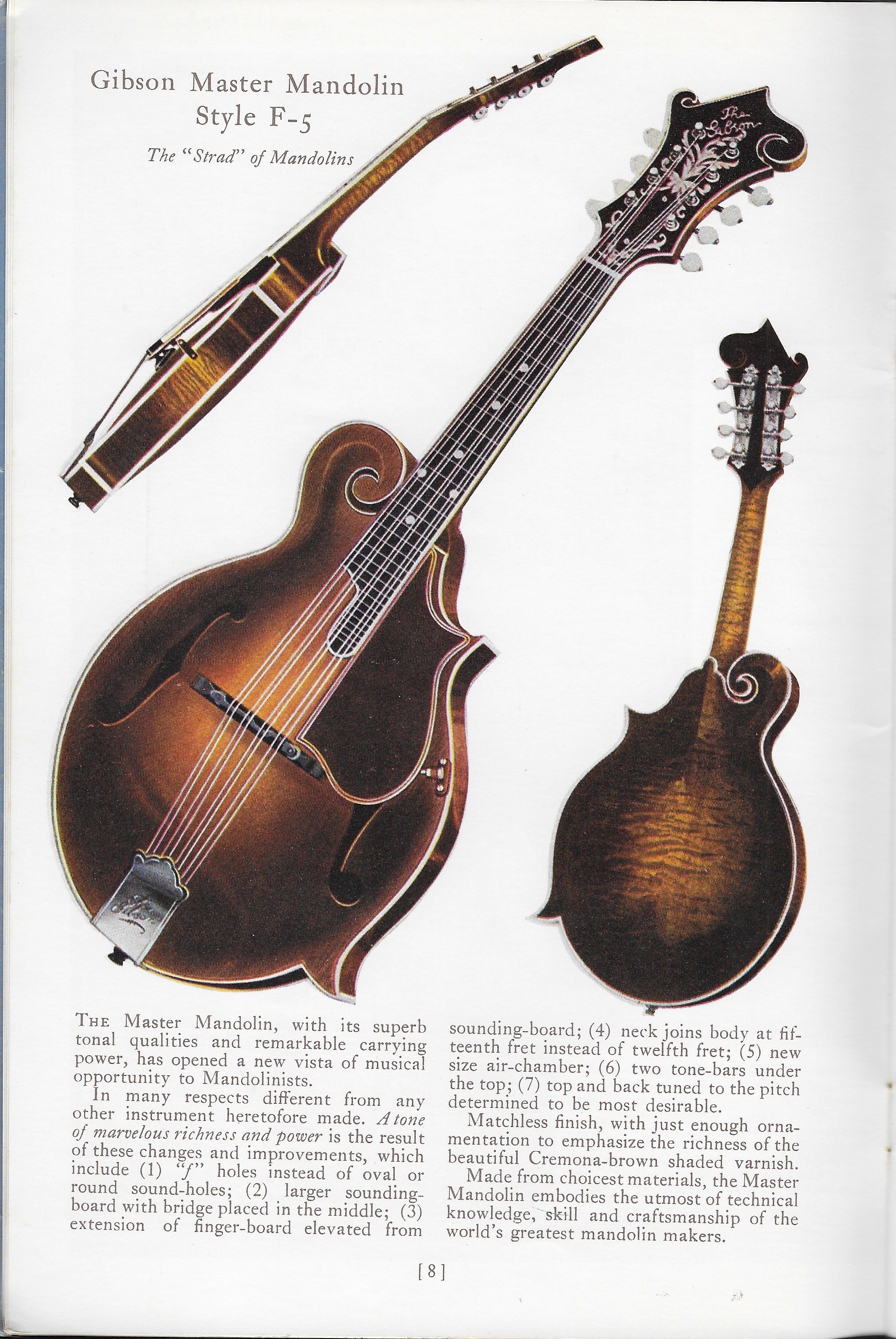

Buttelman remained at Gibson sharing the General Manager title with Ferris until at least January of 1924. His lasting legacy is evident when we open the pages of Gibson’s catalog “N.” (a copy was provided to Walter Jacobs in time for the January 1, 1924 issue of the Cadenza). Along with production manager D. C. Mafit and Lloyd Loar, the three men created a 60-page masterpiece showcasing the full line of instruments. Most famously, an artist’s rendering of the Master Model F-5 appears—in full color— for the first time in a Gibson catalog.

Cadenza, January 1924.

The first appearance of the Master Model F-5 in a Gibson catalog created in 1923, in circulation by January 1, 1924.

The original cover of Catalog N, created by C.V. Buttelman, D. C. Mafit and Lloyd Loar in 1923.

The second run of Catalog N was reduced to 30 pages, printed in black and white on less expensive paper and with fewer photos and illustrations: more of Ferris’ cost cutting.

Before coming to Gibson in 1917, Buttleman had been advertising manager for publisher Walter Jacobs in Boston, working via mail and telephone while maintaining residence in Jackson, Michigan, and managing the Jackson School of Music. Based on articles in both Cadenza and Music Trades, he still held a title at Gibson on January 25, 1924, and he first appears on the masthead of the Cadenza in February of 1924. The city directory of Kalamazoo shows he continued to have a residence there in 1924 with his wife Eulalia, who was a music teacher and a member of the Mendellsson Trio. It wasn’t until late summer of 1924 that he and Eulalia acquired residence in West Newton, Massachusetts.

Music Trades, July 5, 1924.

Both Loar and Buttleman had their exit strategy from Gibson focused on Walter Jacobs Publications in Boston. Loar had submitted a number of articles to those magazines during his tenure at Gibson, many of which we have documented in this journal. Those articles were written in Kalamazoo and submitted through the mail. On the masthead of the January, 1925, issue of Jacobs’ Melody magazine Lloyd Loar appears for the first time as editor, along with manager C.V. Buttleman. The previous editor, Myron Freeze, was still at this post for the December 1924 issue.

Lloyd Loar’s first appearance on the masthead of a Jacobs publication, January, 1925.

Of special interest to our readers, especially those who own F-5s with a December, 1924, signature date: Exactly when did Lloyd Loar leave Gibson? Esteemed Lloyd Loar biographer Roger Siminoff, in his landmark book, “The Life and Work of Lloyd Allare Loar,” has published an agreement between Guy Hart and Lloyd Loar dated October 17, 1924. This documents the “final payment on patent contracts and royalties.” Some scholars take this as proof of Loar’s “last day at Gibson,” but nowhere in this document have we seen any text that specifically confirms a termination of employment (This document does explain why Lloyd Loar’s name does not appear on any patents for the design innovations created during his time at Gibson). Most likely it was indeed the beginning of the end of Loar’s time at Gibson, but was that actually the day he was out the door? We interviewed several business experts and have been told that when a key executive leaves a company, unless that executive is being removed for misconduct, a notice period of 14-90 days after termination is customary. And what about the December 1924 signature date? Of course, for the signatures on the April 25, 1923 labels, we have shown that Loar was in Washington, D.C. So there is precedence that his presence in teh factory at Kalamazoo was not always required for a signature on a given date.

Signature and date on F-5 79756.

The city directory in Kalamazoo lists Loar’s residence in the boarding house on 216 S Park Street from 1920 to 1923. We suspect he moved out of the boarding house in late 1923, as there is no mention of him anywhere in the 1924 directory. (He did not move into the house at 315 Woodward Ave until 1933). He does not show up in the Boston directory until 1925. So where was Loar in ‘24? We promise to continue our research for primary source documents and would love to shine more light on this mystery if possible. In October 2024, we will share our findings in “Breaking News: 1924.” In later years, Buttelman, Williams and Loar all lived in Evanston, Illinois. We like to imagine them gathering to share cigars...

During the shake-up upstairs and the departure of Williams in October of 1923, Loar remained focused on his work; one of his most gratifying duties must have been welcoming musicians who came to try out the new mandolins. The following letter from William Place, Jr. describes just such a meeting; Place returns home with F-5 73676 and by the end of August places an order for an additional two F-5s, probably for his orchestra members in Providence, Rhode Island.

Letter to Lloyd Loar from William Plaxce, Jr., published in Cadenza, October, 1923.

Articles in the music magazines confirm that Loar continued to teach music in Kalamazoo through 1924.

Cadenza, October, 1924.

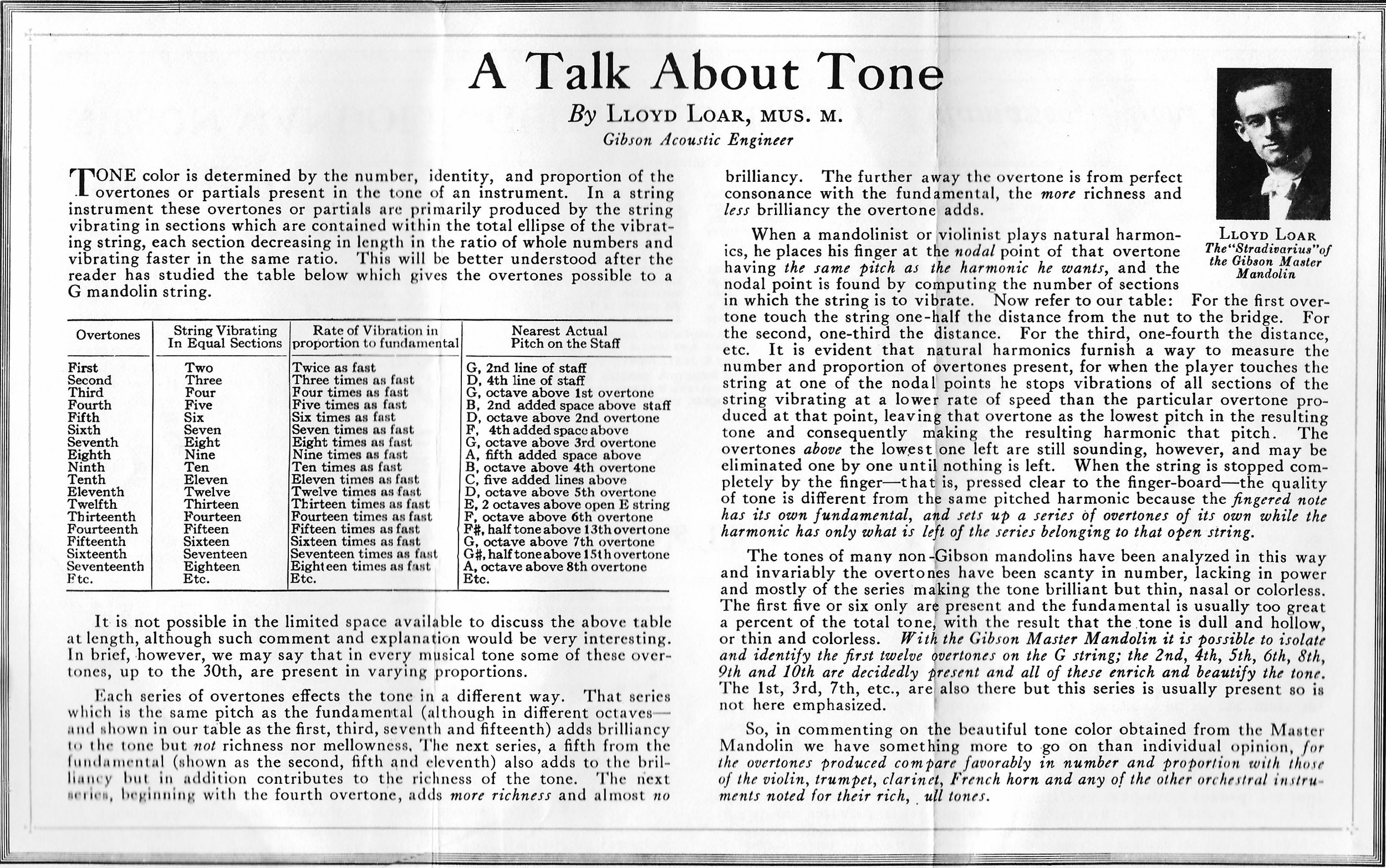

In addition to his focus on Gibson mandolins and mentoring gifted students, Loar continued writing articles on his exploration of the acoustical possibilities of musical instruments. In the October 1923 issue of the Crescendo, a lengthy article entitled “Overtones” describes his findings in some detail. In it, he ascribes the tonal character of a particular instrument to the quality and quantity of the partials, or overtones. A very much condensed version of this description of acoustical properties of the instruments, especially the F-5, appears in “A Talk About Tone” included in the fold-out entitled “Master Model.”

In the article “Overtones,” Loar invites the reader to perform a simple experiment to help the musician understand how the quality and quantity of overtones, or partials, contribute to the tone of the instrument. This experiment also demonstrates how, on an instrument of sufficient quality, up to 60 partials can be heard with the human ear. For our readers, we have included a short video replicating Lloyd Loar’s experiment on overtones: