Chicago Mandolin Orchestra, Claud Rowden, director. This photo was published in the Crescendo, November, 1925, and Gibson catalog P, page 35. (Restoration of the catalog photo courtesy Roger Siminoff). Lovetta Tabaka, front left.

The Chicago Mandolin Orchestra was one of the first to incorporate Gibson’s Master Model Instruments into their ensembles. In this, our last episode of “Breaking News: 1923,” we will continue to identify musicians, from touring professionals to hometown amateurs, who were among the “First Generation of Loar Owners.”

Lovetta Tabaka with Gibson F5. Photo from Gibson Catalog N (autumn of 1923).

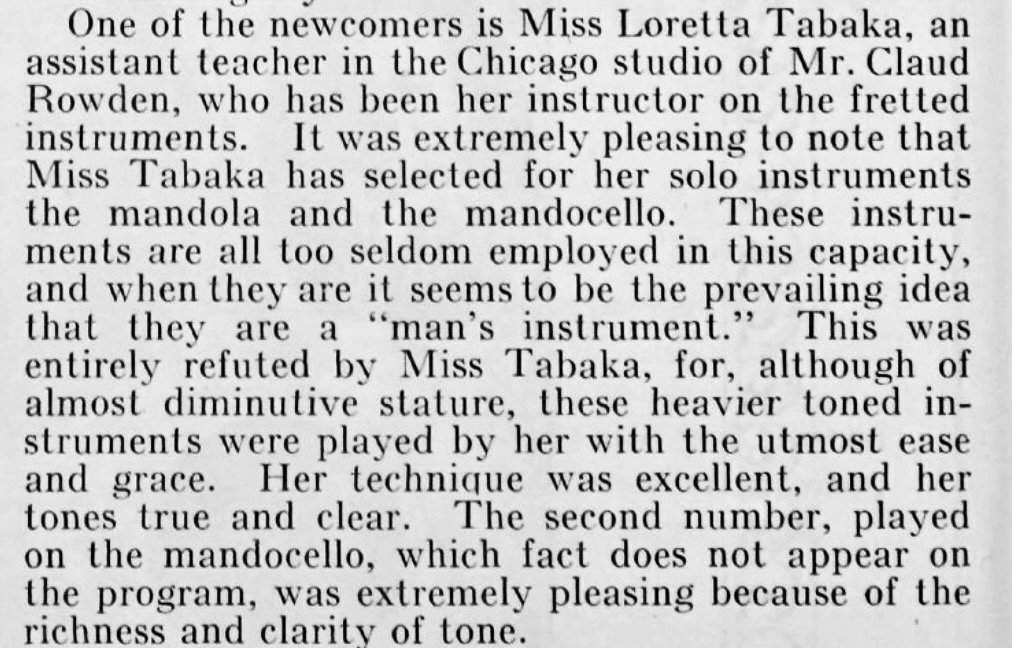

Petite and lovely, 20-year-old Lovetta Anna Tabaka had taken Chicago by storm with her Gibson F-5 by the end of 1923. Within the next few years, awareness of her talent blossomed beyond the windy city as reviews of her performances expounded on her “powerful tone and silky tremolo.” In addition to the mandolin, she played and taught guitar, banjo, mandola and mandocello. In 1926 and ‘27, she charmed the audiences at the Conventions of The American Guild of Banjoists, Mandolinists and Guitarists with brilliant performances on a Gibson mandocello (as a member of the Chicago Mandolin Orchestra, she had access to both K4 and K5 models). Reviewers observed that the instrument seemed to dwarf her in size.

Croscendo, July 1925, p. 6.

Notice for a radio program, Suburbanite Economist, Chicago, Illinois, May 24, 1927

Lovetta Tabaka, Suburbanite Economist, Chicago, Illinois, May 24, 1927.

Detail of the concert program from the American Guild Convention., April 1925. Crescendo, May, 1925.

Concert program excerpt, Chicago Mandolin Orchestra, Washington, D.C., April 11, 1926. Crescendo, June, 1926.

Lovetta Tabaka was born in Chicago on October 23, 1903 to Polish immigrants John Tabaka, born in Wiktoryn in 1869, and Katarzyna Pajak Banach, born in Gdansk in 1884. Much of what we know of the Tabaka family comes from Katarzyna, who lived in Chicago until the age of 96 and kept a scrapbook of photos. John and Katarzyna were married in Chicago in 1900 and had four daughters, Genevieve (born, 1902), Lovetta (1903), Wanda (1904) and Monika (1909). The traditional music of the parents’ homeland was a part of life for the girls, and Genevieve and Lovetta began playing mandolin at early ages.

Photo taken at a Tabaka family outing, circa 1914. Most likely, this is older sister Genevieve with guitar.

The Tabaka home, west-side Chicago, early ‘teens.

Other family members did not receive Katarzyna’s gift of longevity. Baby sister Monika died of illness in 1912, and John Tabaka, who worked in a lumber mill, was killed tragically on January 11, 1915, when a truckload of logs fell and crushed him. Twelve-year-old Lovetta was virtually inconsolable, and only her father’s mandolin seemed to give her any relief. She doesn’t appear with her sisters in any of the family photos after her father’s death, and lost all desire for those Sunday outings after her mother remarried on June 30, 1918.

The Tabaka sisters, Genevieve, Lovetta, and Wanda. While the family scrapbook is filled with later images of Genevieve and Wanda, this is the last photo we have found of the three sisters together.

Lovetta became a loner. However, with countless hours spent with the old bowl back mandolin, her skill progressed rapidly. In the summer of 1918, the diminutive 15-year old passed through the entrance of the towering Masonic Hall, which occupied the block at Randolph and State Streets in Chicago. After growing up in the Polish neighborhood on the west side, it must have felt like passing through to another dimension. There, in Suite 1022, she entered the studios of one of the most successful mandolin teachers and orchestra leaders in American, Claud Clay Rowden.

The Masonic Hall, 1918 City Directory, Chicago, Illinois,

We like to imagine Mr. Rowden arriving one morning to find Lovetta on the steps playing “Czardas” with astonishing speed. However it came to pass, he welcomed her into the program, undoubtedly on scholarship. Clearly, she had entered an astounding world of music, dedication and accomplishment. Within five years, she was on the faculty and took the first chair mandolin in the orchestra.

Chicago Mandolin Orchestra, Handel Hall in Chicago, Illinois, with Claud Rowden, director. Photo from 1918 Gibson catalog K. This is the Orchestra as it appeared when Tabaka first entered the Rowden program.

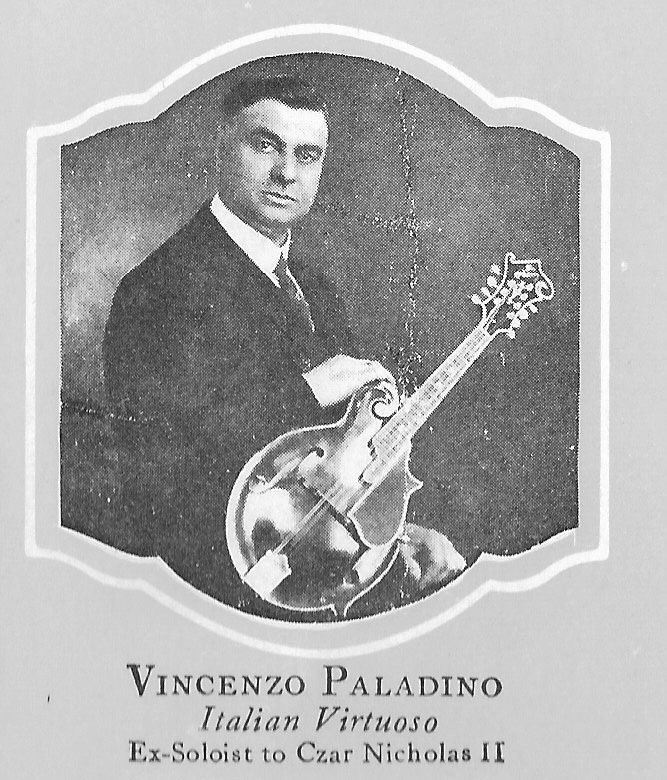

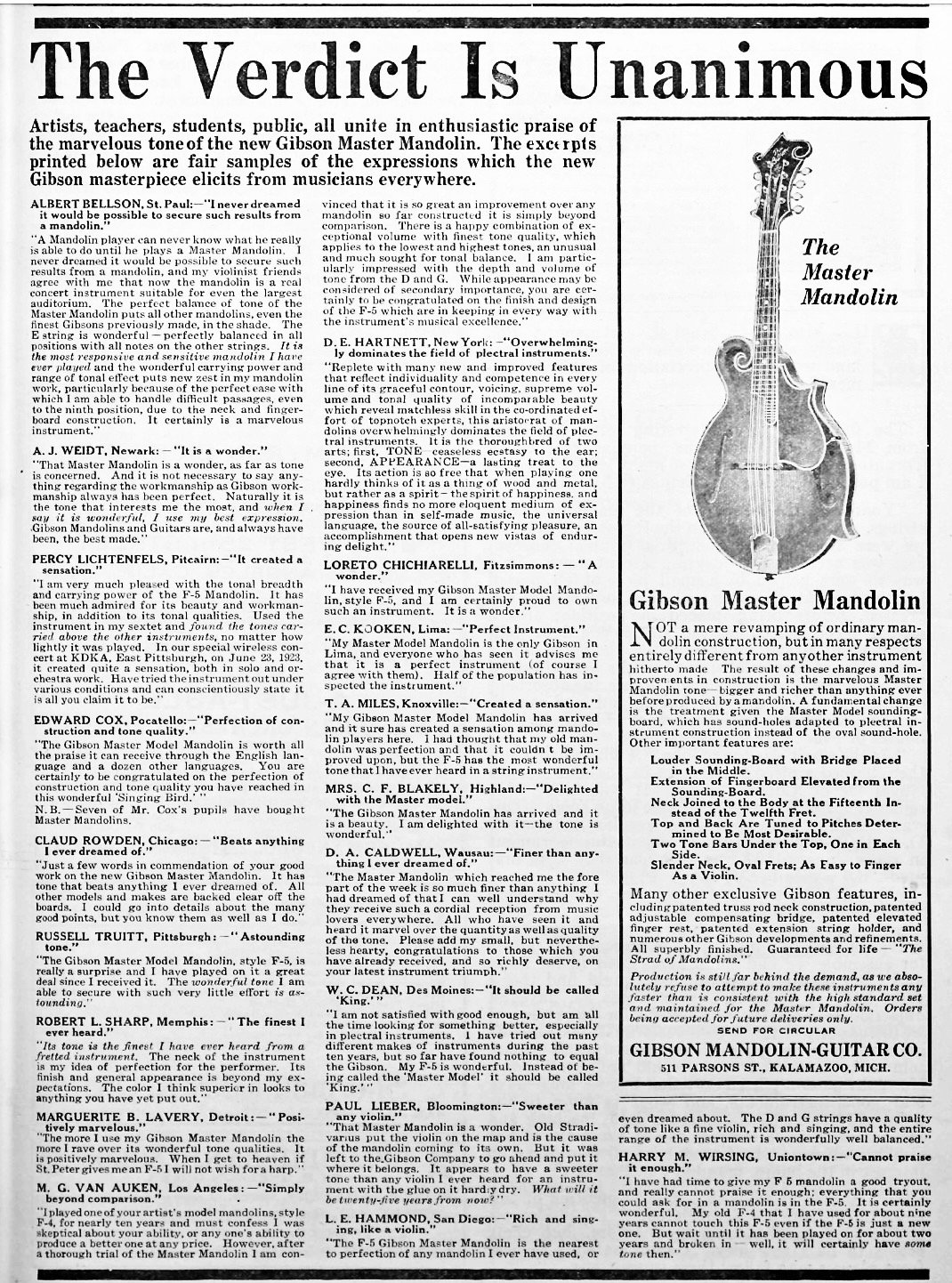

Claud Rowden was one of the first major orchestra leaders to embrace the Gibson Master Model instruments. In a letter to Gibson published in the Cadenza in October of 1923, he wrote “Just a few words in commendation of your good work on the new Gibson Master Mandolin. It has tone that beats anything I ever dreamed of. All other models and makes are backed clear off the boards.” In an interview for a profile in the November, 1925 issue of the Crescendo, he explained his philosophy as an orchestra leader and stressed the necessity to have good players and great quality instruments. Note that he had separate orchestras for banjo and mandolin, and never mixed repertoire.

Claud Rowden, circa 1912, with Gibson Harp Guitar.

Claud Clay Rowden was born on September 23, 1869 in Hartford City, Indiana. He was the same age as Lovetta’s father. Rowden, an accomplished musician, moved to Chicago in 1902 to accept a position on the faculty of the Balatka College of Music at Handel Hall. The College was founded by an Austrian immigrant, Hans Balatka, who had become a leading music teacher in the midwest in the late 19th Century. When Rowden came to town, Balatka’s son Christian had inherited the position at the head of the College, and daughter Anna was a teacher. Rowden, a handsome and charismatic man, married Anna Balakta on February 25, 1903, and the couple took up residence at 3600 Wabash Avenue. What was evidently a stormy marriage only lasted a little over a year, ending in a scandal which rocked the tight-knit music community. Divorce was granted on May 1, 1904.

The Inter Ocean (left) and Chicago Daily Tribune, both on 17 April 1904.

Rowden left Balatka College taking many of the students with him. By 1905, he had once again acquired the use of Handell Hall for his orchestra concerts, and had also established a studio in the Majestic Temple, room 415, 40 Randolph St., for classes and individual instruction. On September 2, 1905, he married one of his students, 26-year-old Nourmahal (Nourma) Excell Bensley, who became a teacher in his growing school. By 1910, he was President of the American Guild, and was performing at the conventions in Boston and Philadelphia as a soloist as well as showcasing gifted students in ensemble presentations. In 1912, he brought the convention to the Hotel Sherman in Chicago, the first time the Guild had left the East Coast. This particularly synchronistic event brought together the leaders of the Eastern plectral community such as Herbert Forrest Odell, Walter Jacobs and D. E. Hartnett with those of the mid-west. At the Gibson exhibit, Sales Manager Lewis A. Williams, Factory Superintendent George D. Lauren and Sales Clerk Charles N. White demonstrated instruments and took orders; even the top brass was there: President John W. Adams, General Manager Sylvo Reams and his assistant and brother, Andrew J. Reams. The young mandolinist from Oberlin College, Lloyd Loar, would certainly not have wanted to miss this event. As leader of the Oberlin Mandolin Club, wouldn’t he have wanted to organize a field trip to Chicago?

The June issue of the Cadenza gives a detailed account of the Chicago Convention.

By the 1920s, Rowden had organized a spectacular music empire in Chicago, as he continued to populate all his organizations with the finest Gibson instruments. Less successful at home, his marriage to Nourma ended in divorce. In 1928, the 59-year-old Rowden married another student, 23-year old Violet M. Carson from Missouri. After the stock market crash of 1929, Rowden and his wife left Chicago and moved to San Diego, California, where they lived together until his death in 1945 at the age of 75.

Lovetta Tabaka continued to wow audiences all though the 1920s, but opportunities for her diminished in the following decade. It is also possible that Claud and Nourma Rowden had filled the void for the girl estranged from her family, and the divorce was hard for her to accept. On October 1, 1929, she married Taba A. Darling, and the couple endured the Great Depression in Chicago. When her marriage ended in divorce in 1939, she moved to San Francisco where she passed away three years later at the age of 39.

Lovetta Tabaka, circa 1913.

Front overleaf of Gibson Catalog “N” compiled in the autumn in 1923.

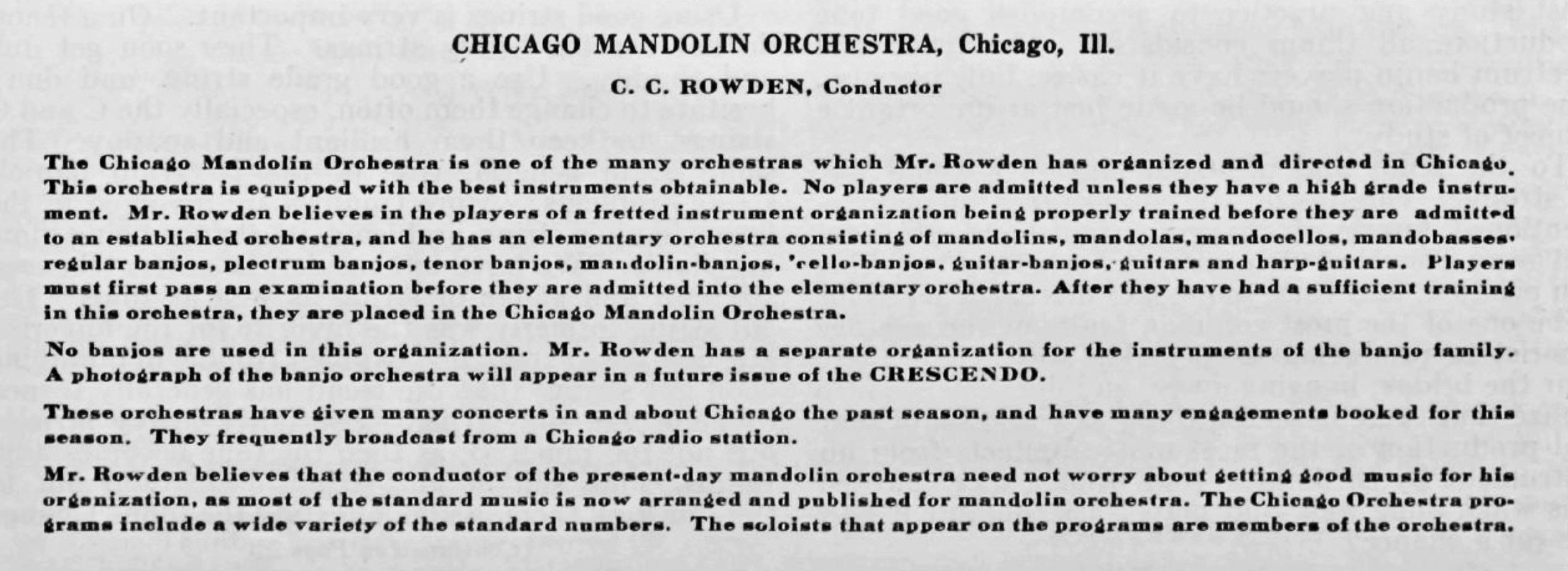

Vincenzo Paladino joins William Place , Jr., as one of the first to record the Gibson F-5. We have yet to discover the details of what must have been an exciting career in Europe, but by 1918 he had landed in New York City. In the late 1920s, he recorded for OKEH and Brunswick Records (a discography is available [with selected sound-bytes} at UC Santa Barbara Library webpage). Paladino’s radio programs on NBC, broadcast from New York City, earned him national recognition for traditional Italian and Classical music. During the Great Depression, thanks to a WPA grant, he organized a children’s orchestra in New York City. Their well-played, authentic Italian sound defied the fact that the oldest member was only 8 years old.

Like Walter Kaye Bauer, Paladino endorsed Vega mandolins as well as Gibson in the late ‘20s. Daily News, Feb 5, 1928_

In Knoxville, Thomas Arville Miles (1880-1941), inspired by the Griffith School of Music in Atlanta, became a leader of the mandolin community of Eastern Tennessee. Miles Music Store at 407 Western Avenue taught and sold mandolins, banjos and guitars, and organized orchestras for the accomplished students. When he received his first F-5, he wrote to Gibson: “My Gibson Master Model Mandolin has arrived, and it sure has created a sensation among mandolin players here. I have thought that my old mandolin (an F-4) was perfection, and that it couldn’t be improved upon, but the F-5 has the most wonderful tone that I have ever heard in a string instrument.” (Crescendo, October, 1923)

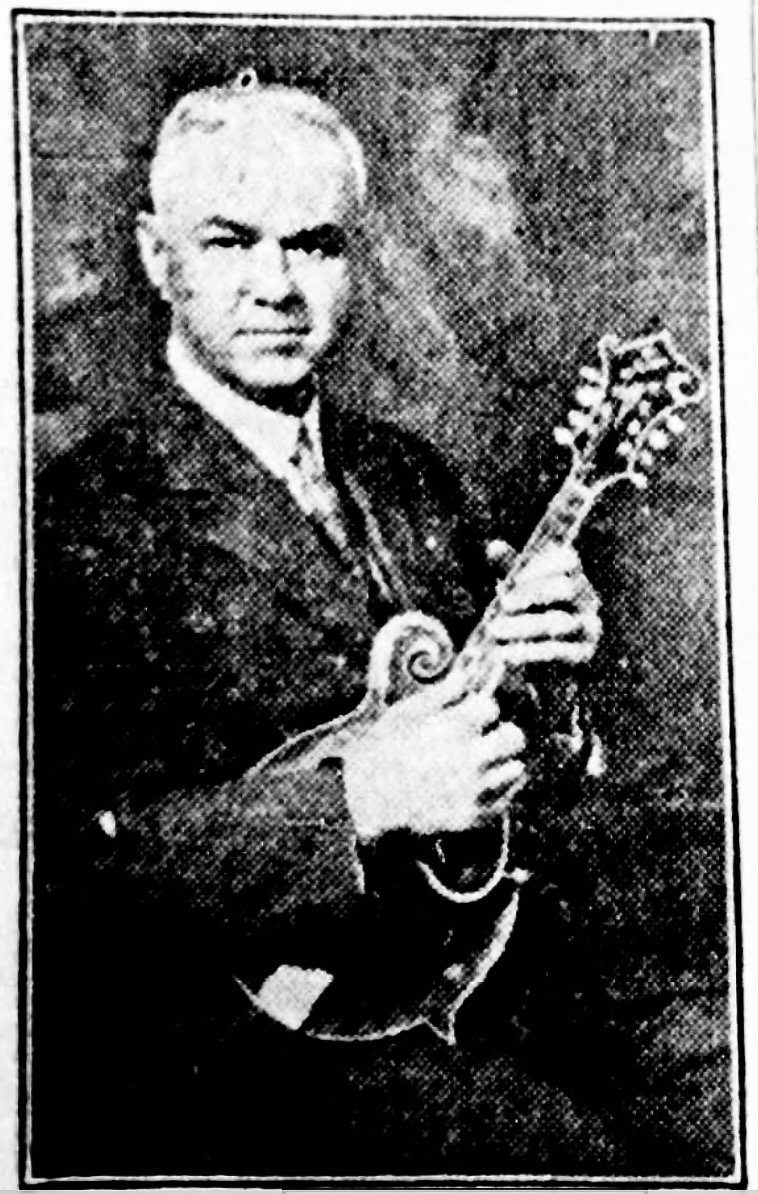

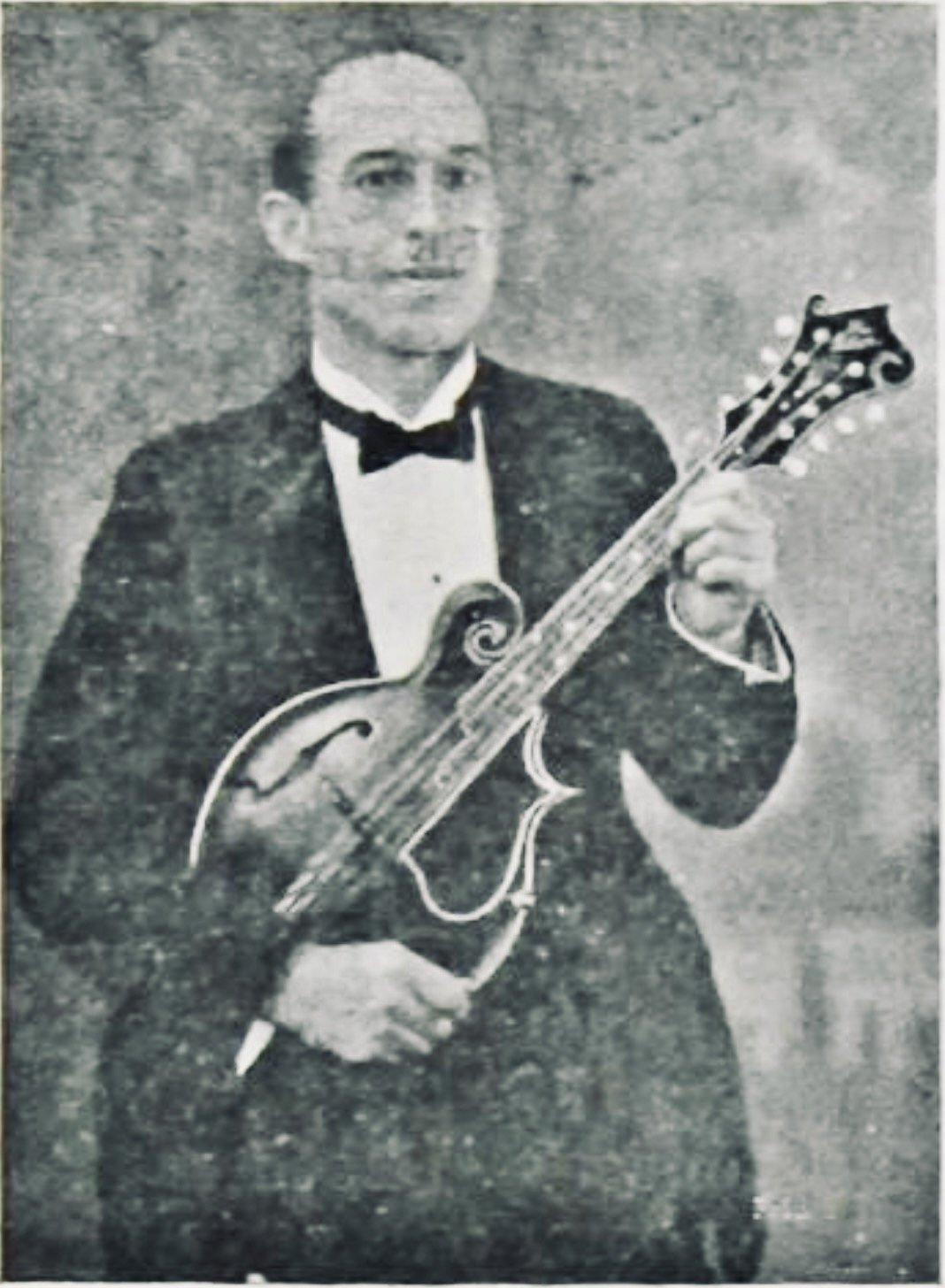

T. A. Miles with a Gibson F-5. He ordered a number of Master Models from Gibson in the 1920s, including two that have become familiar to Bluegrass Audiences: The Charles Bailey/Bobby Osborne 1926 Fern and the Marty Stuart/Wyatt Ellis March 31, 1924 Loar. Photo from The Knoxville News Sentinel, October 21, 1928.

T. A. Miles shown in an older photo with his F-4. Knoxville News-Sentinel (Knoxville, Tennessee) November 3, 1929.

A glimpse into the repertoire of the Miles Mandolin Orchestra. The Knoxville News, May 8, 1924_

In addition to mandolin and banjo orchestras, Miles cashed in on the Hawaiian craze using Gibson guitars with elevated nuts and slides. Knoxville Sentinel, 1921.

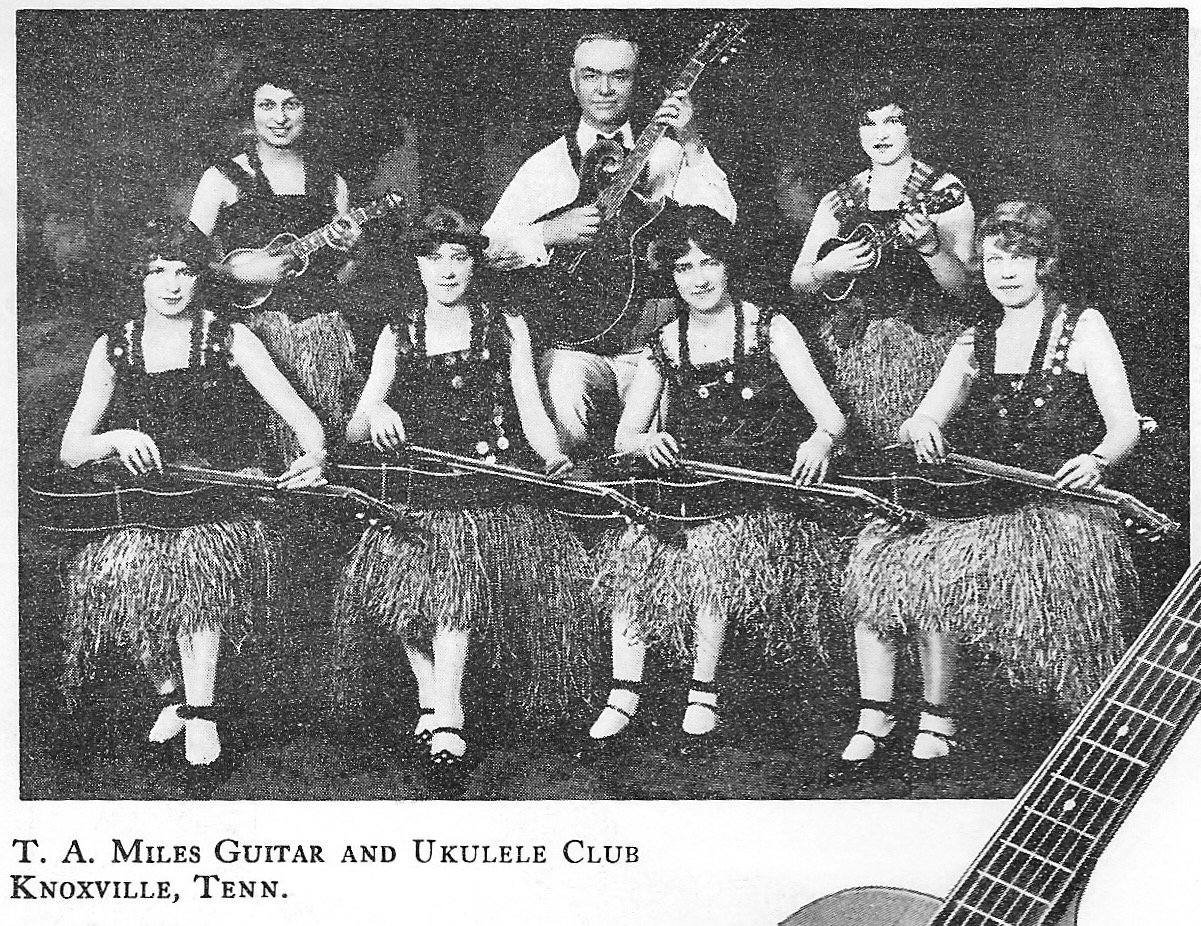

By 1924, the popular group had added ukuleles and grass skirts to their show. Gibson Catalog P. p. 16.

In Memphis, Tennessee, Robert Sharpe had a clear idea of his role as teacher, Gibson dealer and orchestra leader. He wrote “We will not perform where music will not be heard… Music is to the soul what food is to the body.” His ensembles, the Memphis Plectral Orchestra and the Allegro Mandolin Septet had already become well known to audiences in Western Tennessee when he received his F-5. He wrote to Gibson “The tone is the finest I have ever heard from a fretted instrument. The neck of the instrument is my idea of perfection for the performer. Its finish and general appearance is beyond my expectations. The color I think superior and looks to anything you have yet put out.” In addition to this acquisition, by 1926 he had managed to acquire F-5s for his orchestra members H. C. McClelland, Dr. C. E. Warde, Ames Sharp and Ernest Scoutaris.

Crescendo, December, 1925.

Crescendo, December 1925.

Crescendo, July 1926.

The Commercial Appeal, Memphis, Tennessee, Jul 4, 1924

Edward Cox and Cox’s Serenaders from Pocatello, Idaho. Edward Cox was a Railroad brakeman who, in February, 1923, formed a mandolin ensemble (See below identification of the personnel). They performed exclusively on Gibson instruments. Mrs. Lucy Angel, Edward Cox and Lenna Christensen hold F-5s and E. F. Logan, an H5. Also shown, Harp guitar, style O guitar, H-4 mandolas, K-4 mandocello and TB-4 and CB-4 banjos. Crescendo, March, 1924.

In “Breaking News: 1923,” we have profiled many teacher/Gibson agent/orchestra leaders who not only acquired personal F-5s but sold those models to colleagues. However, not all of the first Master Model enthusiasts were entrepreneurs. By far, most were employed in other fields and played for relaxation and enjoyment. Some were employees for the railroads, for example, Edward Cox, from Pocatello, Idaho (shown above), was a brakeman who had moonlighted with the Dewey Band before forming his own orchestra; Paul Lieber, Bloomington, Illinois, was a machinist for the Chicago and Alton line; L. E. Hammond was a railroad engineer based in San Diego, California. Earl Kooken, from Lima, Ohio (and later Huntington, W. Va.) was a glass blower. D. A. Caldwell was secretary of the Chamber of Commerce in Wausau, Wisconsin. And some like A. J. Weidt, a composer, arranger, publisher and coach of the Newark, New Jersey Mandolin Orchestra, and William Charles Dean, a music store owner in Des Moines, Iowa, worked in fields related to music. Morris Van Auken was involved in the motion picture industry in Hollywood, California. And, Harry M. Wirsing was a decorated (and wounded) World War I veteran who enjoyed his mandolin in his retirement in Uniontown, Pennsylvania. After the July 9, 1923 batch, Lloyd Loar and Gibson received many letters of accolades for their achievement. A page with a selection of excerpts from those letters was printed in The Cresecendo in October, 1923 and the same material appeared in The Cadenza in November, 1923.

Crescendo, October 1923, page 19. The dating of this magazine supports the observation that all these F5s were either from the July 9, 1923 batch or earlier.

We now conclude “Breaking News: 1923.” As the Lloyd Loar F-5s reach 100 years of age, I created these episodes to celebrate that milestone. I hope you have enjoyed reading and perhaps have new insight into the creation of the Master Model Instruments, and a better understanding of the men and women who built and/or played them.

I wish to thank my faithful readers, and I am grateful for those who have replied with encouragement and/or information, and am especially grateful to those who sent photos and/or stories about their mandolins. I want to thank and acknowledge Roger Siminoff, who has just published his landmark book, “The Life and Work of Lloyd Allarye Loar.” Mr. Siminoff has been deeply involved with this topic for over half a decade, and continues to search for clearer understanding. I wish to thank our foreign correspondent, Mr. Stephen Gilchrist of Lake Gnotuck, Australia, for his keen insight into the most important primary source of all, the instruments themselves; Jeff Foxall, former Walter Kaye Bauer student, for documents and stories about his mentor; Randy Wood, who has, on countless occasions, allowed me to watch as he performed surgery on some of these instruments; and a big thanks to Scott Tichenor for his support and for sharing my episodes with his readers on Mandolin Cafe. Finally, I wish to thank the noted author and editor, Dr. Andrea Deyrup, MD., PhD., for casting an eye on my text and offering suggestions and corrections. To be clear, any mistakes that remain are mine and mine alone. I will now say goodbye until early next year when I plan to return with “Breaking News: 1924.” —Tony Williamson, December 20, 2023.