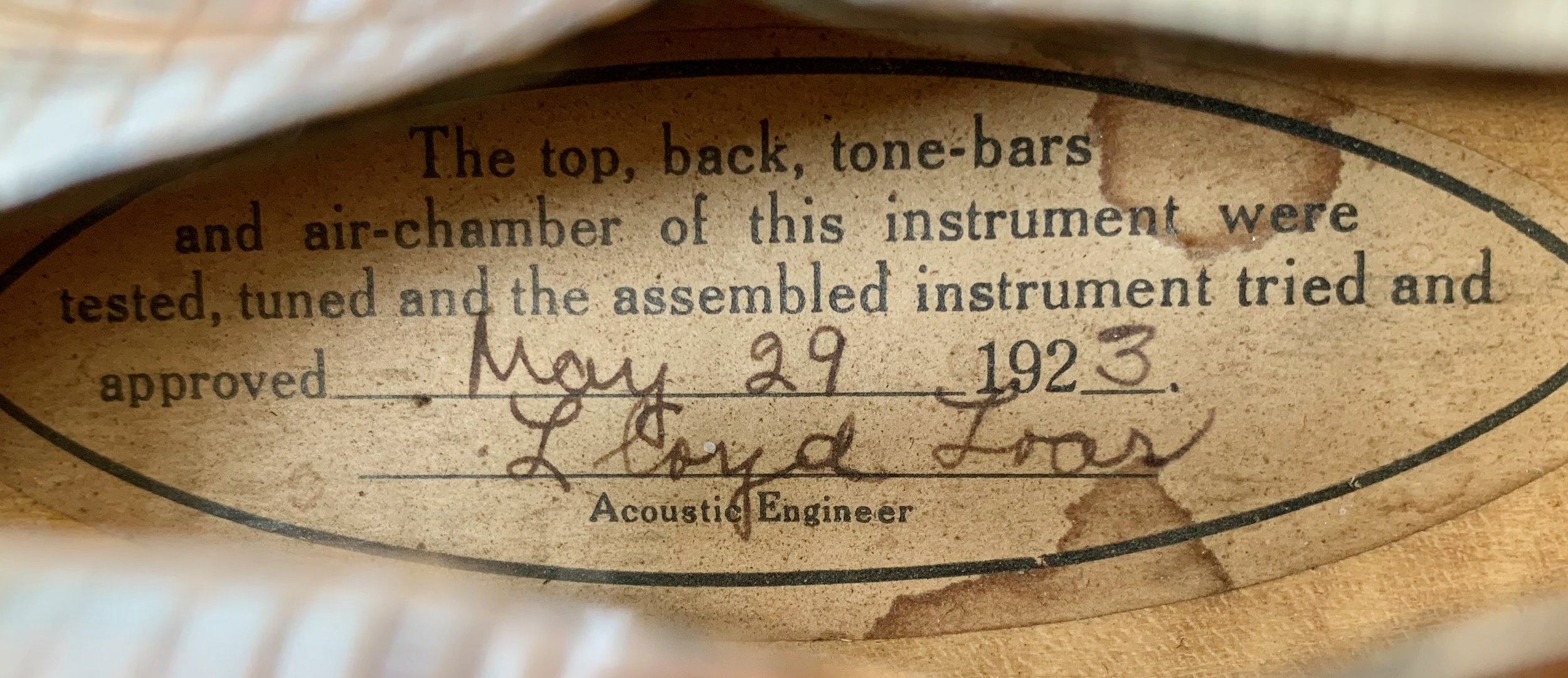

Gibson F-5 73481, signed May 29, 1923. Photo courtesy David McLaughlin.

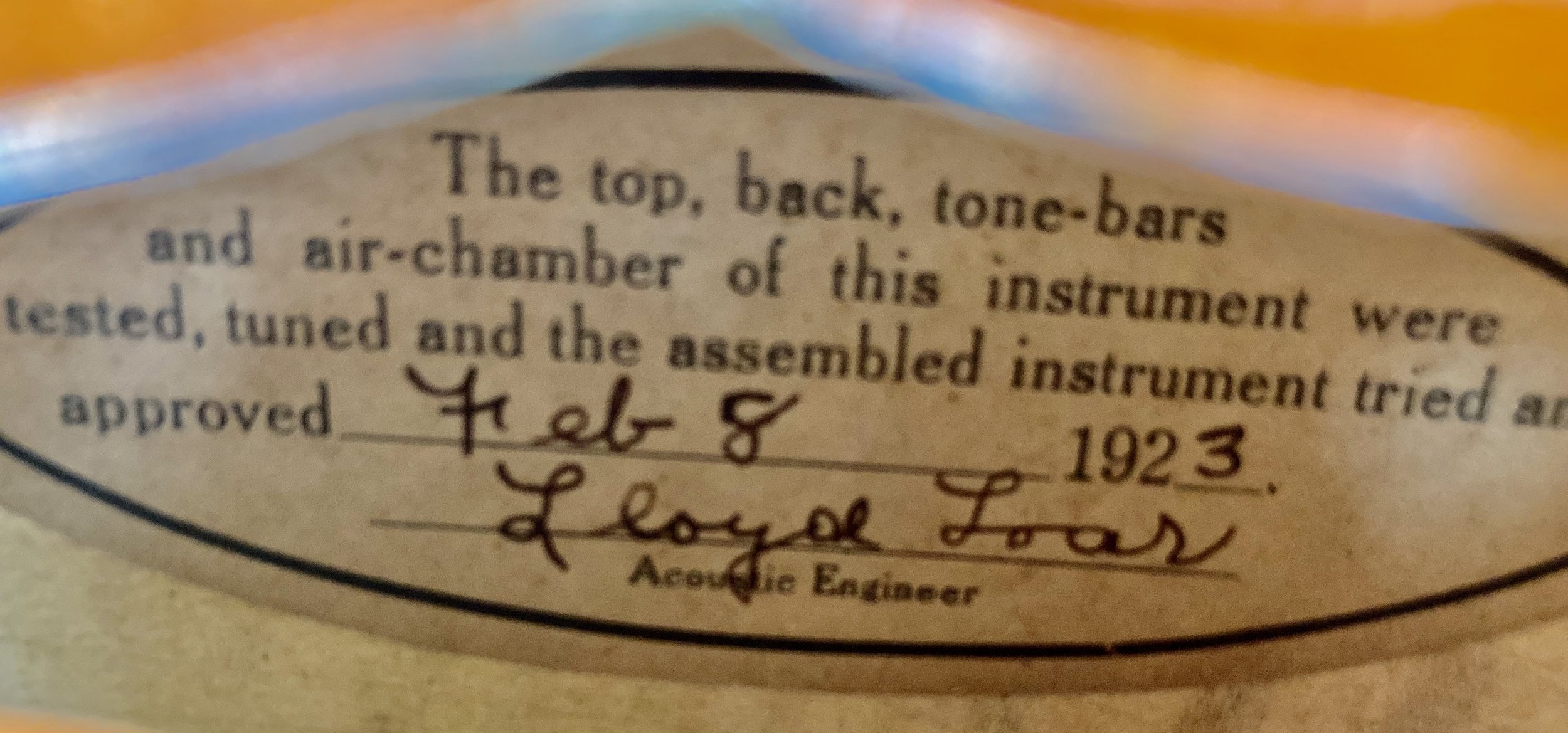

Signature label, Gibson F-5 73481, signed May 29, 1923. Photo courtesy David McLaughlin.

From the beginning, the goal of the Master Model project was to create mandolin family instruments with the power and projection of concert violins. Comparing extant Gibson F-5 mandolins from earlier in 1923 to those produced in the second half of the year, there seems to have been a gradual movement toward darkening the sound and color.

Gibson F-5 73481, signed May 29, 1923. Photo courtesy David McLaughlin.

Possibly less than a dozen F-5s were signed by Lloyd Loar and dated May 29, 1923, the first signature date after the last relatively small batch of April 25. Our featured mandolin this episode was made famous in the 1980s as played by David McLaughlin in the popular Bluegrass band, “The Johnson Mountain Boys.” It is unclear exactly when F-5 #73481 left the factory, but our research has concluded that it was acquired by Adams Byerly for “The Byerly Brothers Music” in Peoria, Illinois. The Byerly Brothers were the only Gibson dealership in Peoria in the 1920s and may have had more than one F-5 (inscribed under the pick guard of 73418 is the serial number 73727, which is a known F-5 signed July 9, 1923). The F-5 was the flagship of a display at the store that included Gibson mandolin family instruments and even a harp guitar.

As the Byerly Brothers franchise grew, they opened a second store in Molline, Illinois, and started a third in Peoria, Adams Music. Driven by public taste and sales numbers, by the late 1940s, they focused almost entirely on pianos, woodwinds and horns. They carried sheet music, marimbas and batons in their inventory, but no mandolins, guitars or banjos could be found there, and there were no lessons available for someone interested in learning those instruments.

Byerly Brothers and Adams music in 1952. Not a mandolin to be found among this impressive list of teachers.

Many of their Gibson instruments, including F5 73481, remained unsold; the entire collection went into storage to make room for the display of pianos. (Many unsold Gibson instruments were returned to the factory, refreshed and sent back to the store, or to other dealers, and the refreshed instruments continued to be offered as new. This process would not have affected the color. Whether or not this was the case with 73481, it remained in new condition and in Byerly inventory until their transition away from stringed instruments).

The storage area was discovered in 1958 by musician and musicologist Mike Seeger of the New Lost City Ramblers. This was one of three Loar-signed F-5s he was known to have had and this is the one he used on their recording of “Long Journey Home.” Around 1980, he passed 73481 on to David McLaughlin. This mandolin can be heard on the many excellent recordings of the Johnson Mountain Boys.

Peghead of Gibson F-5 73481, signed May 29, 1923. Photo courtesy David McLaughlin.

Treble side view of Gibson F-5 73481, signed May 29, 1923. Notice the dove-tail cap on the point. Photo courtesy David McLaughlin.

F-5 73481 heralds a shift in the nature of the F-5. As the “Gibson Cremona Brown” darkens, so does the tone. The F-5s created earlier in 1923 all feature tightly focused projection and crisp clear highs. In late May, there seems to have been a conscious effort to begin a movement toward a darker, richly textured bass, greater complexity overall, while still keeping the characteristic power in all frequencies.

As the Gibsonians were not scheduled to begin their summer tour until July, Lloyd Loar was on duty at the Gibson factory in Kalamazoo during May and June of 1923. The Gibson contingent had just returned from the Guild Convention in Washington, DC (end of April, 1923), and as quite a few of the attendees of the convention became F-5 owners, there must have been optimism toward the project, if not an outright mandate to produce more of that model. It is also reasonable to assume that in addition to orders, there was feedback to be considered. Herman Von Bernewitz, a student of Walter Kaye Bauer, attended the convention as a member of the Nordica Club, the hosts of the convention and the orchestra that boldly performed Beethoven’s 5th Symphony on mandolin and banjo as the finale. Years later, Von Bernewitz recalled meeting Lloyd Loar at the convention and inspecting several F-5s there. He commented to us when we interviewed him in the late 1980s: “I told him they were too bright. I much preferred the sound of my F-4.” As an aside, Von Bernewitz and 7 others left the Nordica Club after the convention to form the Tacoma Mandoleers in hopes of adding lighter selections into their repertoire. The Mandoleers organization has endured, and are still performing 100 years later!

The Nordica Club at the American Guild Convention, Cadenza cover, June, 1923. Herman Von Bernewitz, seated on the conductor’s left. Did Herman’s conversation with Lloyd Loar influence the direction of the F-5?

Perhaps Von Bernewitz’s comments to Loar had impact. Von Bernewitz indicated to us that his observation on brightness was shared by several of his fellow musicians, as they were happy with the mellow sound of oval hole instruments. Whatever the case, the Gibson team seems to have taken steps toward a transition in tone, and curiously, as they darkened tone, they darkened the color. In 1924, Von Bernewitz purchased a gorgeous, great-sounding H-5 mandola, with the dark tone and dark finish. If the team at Gibson came home from the convention with an interest in creating these changes, to whom among the woodworkers would Lloyd Loar, as acoustical engineer, want to discuss this plan? What things would they talk about and then do to alter that tone?

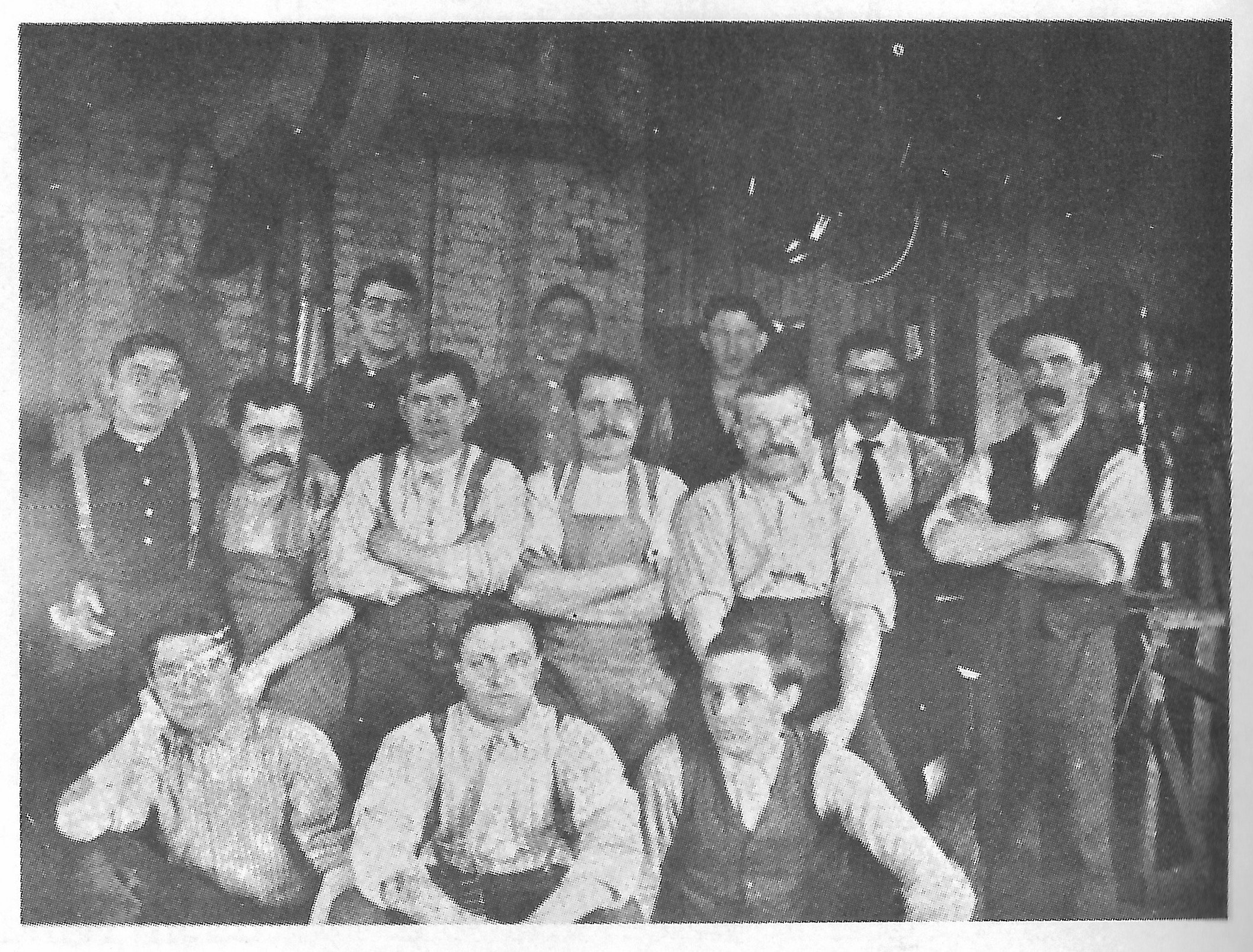

The Gibson team of woodworkers, circa 1915, many of whom were still at work in 1923: George Altermatt, middle row, 3rd from left and Frank Eugene “Gene” Weed, back row on right. Photo from Julius Bellson, “The Gibson Story,” p. 12.

In Episode 4: Shape Brace To This,” we discussed the woodworkers of 1922. While most were still at work in 1923, two longtime Gibson workers seem to have moved into greater roles and may have led the team in new directions. One was George Altermatt, who, in 1925 became foreman and filed a patent for the Mastertone banjo tone ring (he is often attributed as the inventor of the Ball Bearing Ring, but the ball bearings were part of a patent by Victor Kraske and were already in use on the trapdoor banjo in 1922).

We also like to think that the man with the labels was an important ally to Loar. There has long been a controversy around the question of when and where the labels were attached. In our previous episode, we presented the theory that by identifying the person who filled in the serial number labels on the F-5, we may be able to create more understanding of the process of construction. This led us to examining the World War I draft cards from all the Gibson workers. Those cards, required for all men 18 to 45, were filled in by the applicant in cursive, thus giving a perfect handwriting sample! We eliminated workers who could not read and write English; then we found cards for over twenty-five woodworkers, six assemblers, twelve stringers, four finishers, two draftsmen, and a few foremen and managers (Loar, Johnstone and Lewis Williams, for example). (We are happy to share all these handwriting samples with interested parties). Sadly we do not have writing examples from the older employees such as Ted McHugh and Victor Kraske who were well past draft age, nor do we have any samples from the female staff. However, after closely examining all those handwriting samples, only one fits the flowing tail of the letter “F”; this sample also fits the slant and curve of the numbers. So now, we offer the identity of the man with the pencil.

Serial number and model number in pencil on the label of Gibson F5 72060. Notice the slant of the numbers and the sweeping “tail” of the “F.” The appearance of the writing on F5 labels were consistent until an interesting change took place later that summer.

Label of 73481. The bleed through of the finish may indicate a factory refresh. The label was clearly filled out by the same hand as earlier 1923 F-5s. Photo courtesy David McLaughlin.

Draft registration for Frank Eugene Weed, 1917.

Frank Eugene Weed, or “Gene,” as his co-workers called him, was born in Dakota territory, on September 1, 1881. His father, Joseph Edson Weed, was born into a family of farmers in Wales, New York, in 1845. After serving in the 100th New York Infantry during some of the bloodiest campaigns of the Civil War, he came home and married the “girl next door,” Orcelia Fydusia “Carlina” Stephens, and they promptly made their way west to Coopers in Kalamazoo County, Michigan, where he plied the trade of wagon maker. In 1880, events converged to lure him further west: The Homestead Act offered 160 acres of free land to settlers of new territories; after a brutal winter, the rains came to the fertile eastern part of Dakota territory; the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad opened a spur to Pierre, South Dakota; most of the Sioux had been herded onto reservations by the US Calvary; and a new town under construction needed skilled carpenters. Joseph and Carlina headed to Dakota territory to start a new life.

Homesteading in Dakota Territory in 1880: Settlers headed west with the promise of free land..

Gene Weed was born on a farm in Dakota territory as his father helped build the tiny town of Mellette in Spinks County, South Dakota (population in 1890 had grown to around 200; by 1990, it was down to 184). There were no schools, so he learned his letters and arithmetic from his mother. From his father, he learned about farming and woodworking. In 1894, the family gave up the prairie life and moved to back to Kalamazoo where Joseph found work in the carriage industry, and Gene, at 13, went to work as carpenter’s apprentice. By 1910, he was at work at Gibson making mandolins, and continued there as a woodworker until his retirement in 1951. (The 1940 census lists him as “woodworker, Medical Instruments Mfg. Co.” but this is a misprint by the census taker, as his draft card of 1942 lists his employment as “Gibson, Inc. (Guy Hart).”

In the past, scholars have assigned the role of filling in the labels to James Johnstone, the “jazzy” foreman of the stringing department, based on a sentence in the 1921 Gibson Soundboard Salesman: “‘Jimmie’ checks the instruments in on records and fills the orders.” The records referred to were most likely the shipping ledgers, not the serial number label. A look at Johnstone’s handwriting confirms he was not the man with the flowing “F.”

And some still insist Loar himself did these numbers, as was the case on the first F-5, 70281, but in the many examples of his writing, Loar always put a down-stroke on the right side of the bottom flag of the “F.” That figure is consistent in all of his writing samples that we have examined.

What is the conclusion here? First of all, we must mention that the writing on the serial number label takes a distinct change as we move further into 1923. More on that soon to come. But for now, if we can accept Gene Weed as the man with the pencil, we can also infer that the labels, at least in the first half of 1923, were created by a woodworker, not an assembler, stringer or finisher. This may change the way we think about the process, and maybe give new interest in researching the contributions of Eugene Weed, a gifted worker of whom not much has been written.

Gibson F-5 73481, signed May 29, 1923. Photo courtesy David McLaughlin.