L to R: Ethyle Hindbaugh Johnstone; Charles A. Templeman; James Hart Johnstone; Lloyd Loar; Marguerite Lichti. The Gibsonians, as advertised in the August, 1923, Crescendo. Of this group, only Loar performed performed that summer. Fisher Shipp, who was on all the 1923 concerts, was not included in any of the Gibson promotional photos.

Very early on August 6, 1923, Lloyd Loar, Fisher Shipp, and four young musicians left Carlisle, Ohio, on the Springfield Branch of the “Big Four” railroad, en route to Newcastle, Indiana. They had arranged for a driver to meet them at the station and take them south to the Rush County Chautauqua. There was no car awaiting them and none to be hired. The musicians walked, carrying their instruments twenty miles from Newcastle to Rushville, Indiana. They arrived just in time for the 2:15 show. They performed in dusty clothes, hot, tired and hungry. By the 8:30 show they had recovered somewhat, and there was some comfort in knowing that on the next day, August 7th, they would be in Shelbyville, Illinois. The Shelbyville Chautauqua auditorium, which seated 4000, had always been a highlight for Shipp and Loar. They arrived in a heavy rain, stunned by what they saw: a throng of over 10,000 people crowded Forest Park. Many were dressed in hoods and robes. The Ku Klux Klan had overtaken the Shelbyville Chautauqua.

The Decatur Herald, Decatur, Illinois, August 5, 1923.

The Picturesque Chautauqua Auditorium in Forest Park, Shelbyville, Illinois. In this grand auditorium, built in 1903, Fisher Shipp and Lloyd Loar had delighted audiences each summer for nearly 20 years. In 1923, a very different experience awaited them.

What has happened to the Gibsonians? To understand fully, we must take a look back on the events in the months prior to August, 1923.

During June, Lloyd Loar had focused on his work at Gibson, engineering the largest batch of style F-5 Master Mandolins to date. In 1922, as the leader of the Gibsonians, he began taking those instruments on the road, testing them in action and demonstrating their commanding sound. To book many of the performances, he capitalized on the popularity of his wife, Fisher Shipp. Since 1906, Shipp had been under contract with The Lyceum Bureau, which promoted the widespread and highly popular adult education events called the Chautauqua. With the Gibsonian name, they were also able to bring their show to mandolin, banjo and guitar enthusiasts across the country. In April of 1923, Loar’s 10-string mandola solos dazzled audiences; James H. “Jazz” Johnstone, founding member of the Gibsonians, handled the mandobass with as much ease as his tenor banjo; his wife, Ethyle Hindbaugh Johnstone, an accomplished musician in her own right, played a new F5 mandolin; the brilliant young Marguerite Lichti impressed everyone with her solos on the newly introduced L5 guitar, and doubled on H5 mandola; and her mentor and teacher, Charles A. Templeman demonstrated the K-5 mandocello to great advantage in the ensemble. Both the Cadenza and Crescendo magazines advertised that this group would perform that summer, following in the footsteps of the previous year’s edition of the Gibsonians who had entertained “…over 20,000 people (in) 105 performances” from June 20th to September 1st. (Music Trades Review, October, 1922).

The Crescendo, August, 1923. Fisher Shipp, the headliner of the summer program, is not mentioned or photographed in any of the Gibson related print media in 1923.

The summer tour of 1923 was anything but a repeat of the great success of 1922. There was an angry cloud looming in America that threatened the very spirit of education, philosophy, science and inquiry that the Chautauqua represented. Even before the Great Depression dealt the final blow to the summer series, the gatherings were very much in trouble. The Colorado Chautauqua Association pointed out that “in this era of gangsters and rum-runners, many middle Americans have demanded a return to fundamentalist (values);…the non-denominationalism exhibited at most Chautauqua programs cannot accommodate these impulses.” Many former Chautauqua venues were already being converted to camp meetings.

Despite the mistake on his name, this is Lloyd Loar residence while working at Gibson in 1922 & 1923.

Since 1920 when he moved to Kalamazoo, Lloyd Loar had lived in a boarding house at 216 South Park Street and spent his days at the Gibson factory on 225 Parsons St. Fisher Shipp lived with her mother at their home in Brookfield, Missouri. Thanks to the society page of the “The Daily Argus” of Brookfield, Missouri, we have a good record of the couple’s activities. For example, on November 6, 1922, “Fisher Shipp Loar left last night for Kalamazoo to visit Mr. Loar.” In late December, Loar traveled to visit her in Missouri, “returning to Kalamazoo on January 2.” On January 5, “Mrs Fisher Shipp Loar is in Linneus (Missouri) today on business of the Redpath Lyceum Bureau.” After the meeting, she signed a contract with Enos G. Stambach, a 21-year-old pianist who had just graduated Wesleyan College in Cameron Illinois. (Stambach was the son of 63-year-old Enos E. Stambaugh [or Stambach], a farmer living in nearby Meadville). On January 19, this notice appeared in the Daily Argus:

The Daily Argus, January 19, 1923. The first step in a departure from the Gibson Mandolin Orchestra accompaniment of 1922.

In the past, the Lyceum booked the Fisher Shipp Company one hundred or more engagements each year, from Ohio to Saskatchewan. For 1923, there were only sixteen dates available to her, one in Illinois and the rest in Ohio and Indiana. Did the board members of the Lyceum recommend a change in her program, were they in a position to dictate instrumentation? Was there pressure to move away from Loar’s focus on acoustic innovation and the international, multi-cultural repertoire? Did they insist on a return to more “legitimate” instruments like piano and violin? Or was it Shipp that steered the ensemble toward her sound of early 1900s? In 1923, advertisements placed by the Lyceum did not include Lloyd Loar’s name and advertisements generated by Gibson did not include Shipp.

Despite the fact that the music magazines like the Crescendo and Cadenza continued to advertise the Johnstones, Templeman and Lichti for the summer tour, they did not perform again as Gibsonians.

Sioux City Journal, March 29, 1923.

After having been elected to the Board of Directors of the American Guild of Banjo, Mandolin and Guitar at the convention in Washington, DC, Templeman announced that he was now the representative for Dayton mandolins, the eccentric designs of Charles B. Rauch of Dayton, Ohio. It was a stunning revelation, as Templeman had been a prolific proponent of everything Gibson in Sioux City, Iowa, since the mid-teens, and had sold countless Gibson instruments to his students and orchestra. By 1924, Templeman was promoting his own line of mandolins, “The Coulter,” which turned out to be very short lived.

top: Music Trades, November 1924; We have never seen a Coulter instrument. Bottom: Cadenza, April, 1923.

Templeman’s student, Marguerite Lichti, the bright young star who had first introduced the Gibson L-5 guitar to the world in Washington, DC, would not be joining the summer tour either. All accounts indicated that Lichti had all the makings of a world class performer. It is unclear whether she declined the summer tour out of devotion to Templeman, or if they were both phased out by the Lyceum Bureau. In any case, for her, the promise of a national career gave way to the quiet life of a Sioux City teacher.

Marguerite Lichti, the brilliant guitarist that introduced the Gibson L-5 guitar for the first time in Washington, DC in April, 1923. The Crescendo, August, 1923.

Ethyle Johnstone who played first mandolin in April, was already three months pregnant in this photo taken in front of the White House, and was not able to go on the summer tour. Husband James Johnstone elected to stay in Kalamazoo to be with his wife during the last month of her pregnancy.

The Gibsonians at the White House in April of 1923. Lichti, Mrs. and Mr. Johnstone, Templeman and Lloyd Loar. The very promising chemistry of this group was short-lived. Only Loar was left by summer.

In June, Fisher Shipp began rehearsing material with the young pianist in her home in Brookfield.

The Brookfield Argus, Brookfield, Missouri, June 28, 1923.

The Meadville Journal, Meadville, Missouri, July 5, 1923.

On Monday, July 2, Shipp and Stambach were in Kalamazoo to rehearse with Loar and the other musicians. It is unclear whether it was Shipp or Loar that recruited attractive twenty-one year old Marguerite Wood, from Clinton, Illinois, for the group. Just out of high school, she was known for her lovely contralto voice; she also played piano and had acting experience in local productions and school plays. She would join Shipp and Stambach in vocal trios and take roles in staged routines and comedy skits. All that was needed to recreate the sound of Fisher Shipp’s 1910 Concert Company was a violinist. It was most likely Loar that contacted Jacques Gordon, the highly regarded violinist and concertmaster with the Chicago Symphony, but Gordon declined, citing other commitments. Instead, he sent his star pupil, fifteen-year-old violin prodigy John de Voogdt.

Who, then, other than Loar himself, would be playing Gibson instruments in the Gibsonians? Concert reviews consistently referred to the ensemble as a sextet, and it was observed that three of them were men. Perhaps Loar invited one of the Gibson Melody Maids to join the group, as he did the next year? At this point the sixth person remains a mystery.

Marguerite Wood from Clinton, Illinois, and Enos Stambach from Meadville, Missouri, circa 1923.

Left: The summer itinerary; Right, a typical notice, this one from the The Richmond Item, Richmond Indiana, July 5, 1923.

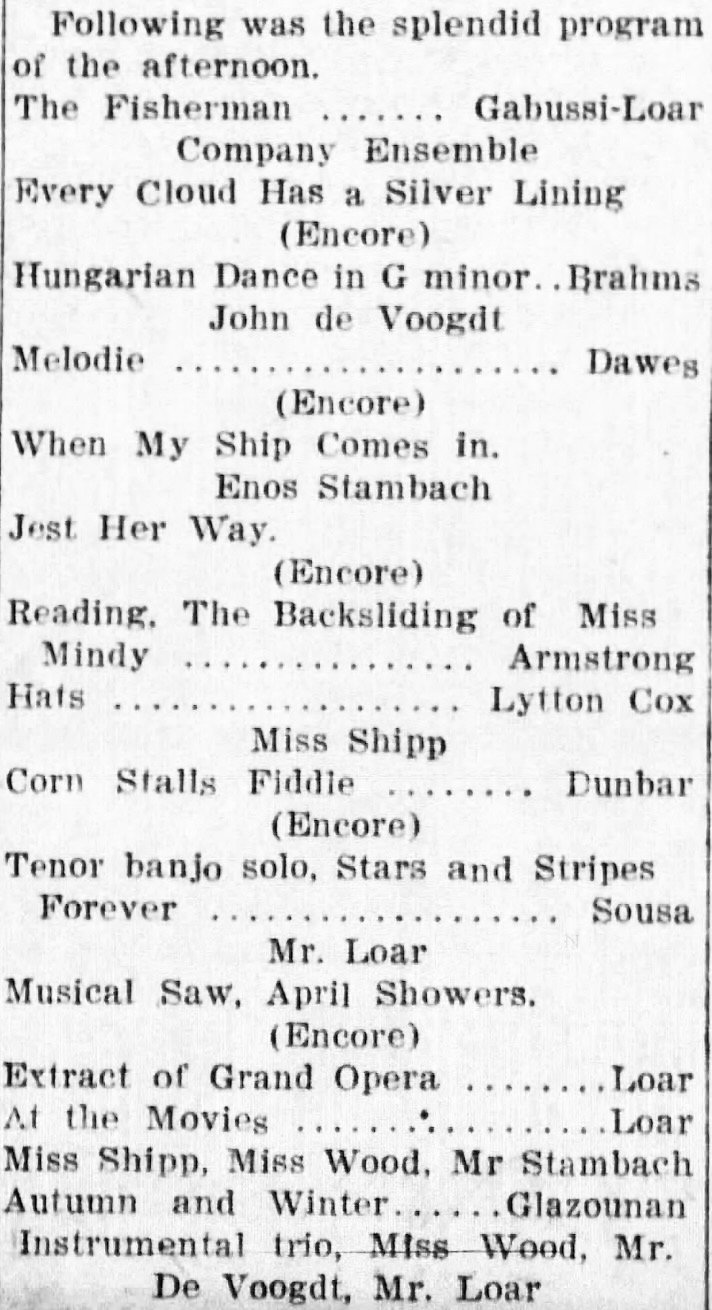

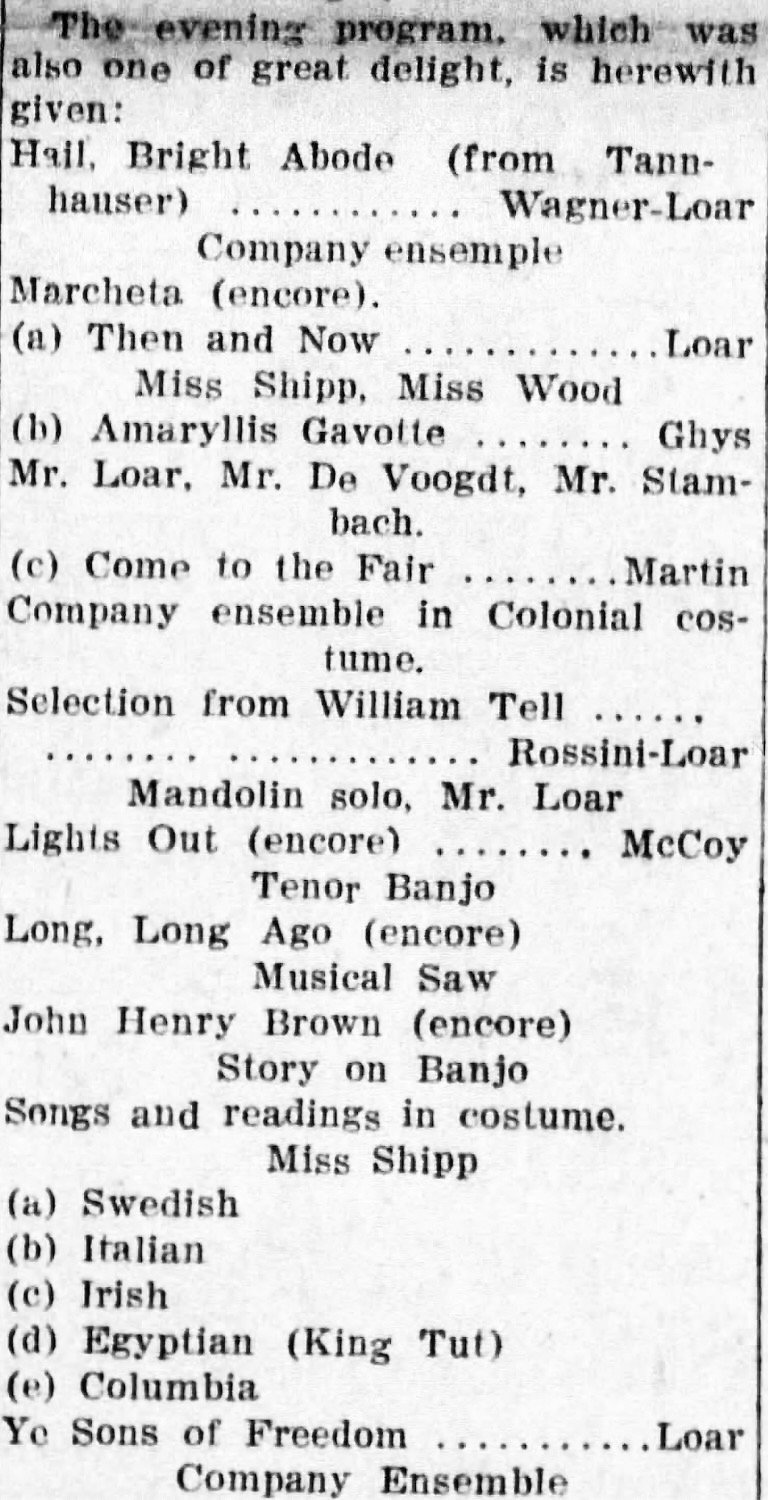

The first show was in Cambridge City, Indiana, and for two months, “Fisher Shipp and the Gibsonians,” shuttled back and forth between Ohio and Indiana. On most venues, they performed an afternoon set of vocals and instrumentals, and a longer evening set that included readings, skits and comedy along with the songs. Thanks to the July 18, 1923, edition of the News Messenger of Fremont, Ohio, we have the program from both shows at the July 17 Fremont Chautauqua and a review of the performance.

The afternoon program of the concert on July 17. The News Messenger, Fremont, Ohio, July 18, 1923.

The evening program of the concert on July 17. The News Messenger, Fremont, Ohio, July 18, 1923.

Review of the concert at the Fremont, Ohio, Chautauqua on July 17. The News Messenger, Fremont, Ohio, July 18, 1923.

In the very early morning of August 6 they arrived in Newcastle, Indiana, expecting transportation. None was available. With determination, they walked to Rushville, carrying instruments and suitcases and arrived just in time for the afternoon performance.

The Daily Republican, Rushville, Indiana, August 7, 1923. Why such a flippant account of their plight?

When they ended the evening show around 10 pm, they were once again stranded. The entire town had been thrown into a frenzy. According to the August 7 edition of the “Daily Republican” of Rushville, “Excitement ran high as a crowd of 500 men armed with revolvers and guns kept watch all night for two suspects” accused of assaulting a young woman. Miss Zella Aldridge, 21, of Rushville, alleged that two African American boys “attacked her and detained her” for over an hour in a field just to the west edge of Sexton. Bloodhounds were brought in from Bedford and the hunt went on all night. On the afternoon of August 7, officers in Shelbyville, Illinois, over two hundred miles away, reported to Sheriff Hunt of Rushville that they had arrested two young African American farmhands. “The Daily Republican” of Rushville (August 7, 1923) printed a detailed account of Miss Aldridge’s lurid story. None of this proved true. There was no evidence at the scene or in the doctors’s examination to support any of her allegations. Finally, by the evening of August 7, Sheriff Hunt dismissed the episode as a “young lady with an overwrought imagination” and declared the entire fiasco a “hoax.” He telephoned the Sheriff of Shelbyville and asked that he release the two men they were holding. The timing of their incarceration could not have been worse, considering what was already happening in Shelbyville that day.

The Daily Republican, August 7, 1923. The fate of the two young African American farmhands arrested in Shelbyville remains unknown.

To understand what awaited the Gibsonians in Shelbyville, we have examined the national sensation, the “Mer Rouge Murders.” On August 24, 1922, in Bastrop, Louisiana, Samuel F. Richards and Filmore Watt Daniels were kidnapped by members of the Mer Rouge Ku Klux Klan and were never seen again. Almost a month later, two bodies were discovered in nearby Lake LaFourche. Since all the local authorities were members of the Klan, the United States Attorney in Louisiana sent A. E. Farland of the Federal Bureau of Investigation to Morehouse Parish, Louisiana, to conduct an investigation. Agent Farland became convinced that the bodies were Richards and Daniels, and, in a detailed report, observed that the men had been “horribly tortured and then lynched.” Farland also uncovered evidence of numerous other crimes perpetrated by the KKK in that area, ranging from election fraud and assault to murder. The U.S. Attorney turned the case over to the Louisiana Attorney General who filed over 250 indictments under Section 241 of the Enforcement Act of 1870, in addition to murder charges for five of the Klansmen and a “Conspiracy to Commit Murder” charge for the man who allegedly ordered the murders, Captain J. K. Skipwell, leader of the Mer Rouge KKK. Over the next year, litigation dragged on. The New York Times published over 100 articles calling for justice. According to Times, Richards and Daniels, who were white, were targeted by the Klan because Daniels had a common law wife who was African American and that they were vocal opponents of the activities, authority and power of the Klan in that county. In their defense, the Klan sent speakers on public relations tours across the country. (“Murder At Mer Rouge” by Hannah Bethann Peterson, Honors Programs, Texas A & M University, April, 2004; “Mer Rouge Terror,” New York Times, November 27, 1922; and “Louisiana Klan Goes On Trial Today”, January 6, 1923).

When the Gibsonians finally arrived at the Shelbyville Chautauqua Auditorium, they found Forest Park in an uproar. Their afternoon show had been usurped by impassioned speakers, all high level members of the Ku Klux Klan. Four thousand people filled the auditorium to capacity and another six thousand, many in hoods and robes, pressed in from outside. Heavy rains added to the confusion. Opponents of the Klan were forcibly evicted. The keynote speaker was Captain J. K. Skipwell himself.

Journal_Gazette, August 8, 1923 Matoon, Illinois.

In his speech, Skipwell asserted, “Those bodies found in the bayou were planted there to manufacture a case against the Klan. We think Daniels and Richards are alive and those bodies are fakes, pure and simple…We know nothing ‘bout it. Only the Catholics and Jews know about that stuff.” He insisted that those “false charges” again the Klan were instigated and paid for by “New York Jews.” Then, Skipwell applauded vigilantism. “The Mer Rouge case resulted from the lawlessness and indecency of Watt Daniels and Tom Richards… Old man Daniels (father of Watt Daniels)… operated a bootlegging business and the lowest of gambling hells. His intimate relations with … (an African American woman) were shocking to respectable citizens. His son was worse and Richards was no better.” He then went on to maintain that “Every Christian man and woman owes a debt to the Klan.” Later in the speech, he blamed “Jews, Catholics, foreigners, immigrants, and (African Americans)” for all the ills of the country. (“Journal Gazette,”Mattoon, Illinois, August 8, 1923; “Effingham Record, Effingham, Illinois, July 27, 1923; The Decatur Herald, Decatur, Illinois, August 5 and 8, 1923)

For the full story, with disturbing details, see The_Decatur_Herald, August 8, 1923.

Advanced advertisement for the Shelbyville Chautauqua announced that two bands would be playing: Goforth’s Orchestra and Fisher Shipp and the Gibsonians. It does appear that Goforth performed the night before on August 6, but there is no mention of any performance by the Gibsonians in any accounts written afterwards.

Grafitti on the wall of the dressing room behind the stage at Shelbyville could still be seen there upon our last visit to Forest Park.

The Mer Rouge murder trials continued on into 1924. According to sources, the juries were stacked with Klan sympathizers. The Governor and Attorney who prosecuted the indictments lost re-election, and the new Louisiana Attorney General dropped all charges due to “insufficient evidence.”

After Shelbyville, the Gibsonians played the last four engagements of their tour without incident. Fisher Shipp went back to Brookfield; Enos Stambach took a job as music director and organist at the Star Theatre in Nevada, Missouri, and later the Gillois theatre in Springfield, Missouri; Marguerite Wood settled for quiet life of school teacher in her hometown of Clinton, Illinois; We have found no evidence of John de Voogdt’s musical career after this tour.

Finally, a happy note: proud parents James and Ethyle Johnstone announced the birth of Marion Francis Johnstone on August 28, a healthy baby girl. “Jumpin’ Jazz” Johnstone would be back with his tenor banjo and mando-bass for future Gibsonian programs.

The Crescendo, September, 1923.

Lloyd Loar returned to Kalamazoo to turn his attention to putting even larger batches of Master Models into production, and writing articles on acoustics, including one on overtone production in stringed instruments. Loar was a man deeply rooted in two worlds: On the one, he was a scientist, a theosophist, an inventor, an international traveler, a multi-linguist and a teacher; on the other, he was a musician, composer and band leader. During his tenure as Acoustic Engineer at Gibson, he blended both worlds brilliantly, and for that work in those brief four years, we honor him today and his name will be heralded for generations. After the trials and tribulations of the summer tour of 1923, he may have begun to seriously consider giving more priority to his “other interests and pursuits.”

Lloyd Loar, The Crescendo, July, 1922.