L to R: Leora Haight, Walla Zeller, Lloyd Loar, April 26, 1922. Along with James H. Johnstone, they had just performed with the Kola Orchestra in Passaic, New Jersey.

On the morning of June 9, 1922, Lloyd Loar received his copy of the June issue of the Lyceum magazine at the boarding house on 225 Park Street in Kalamazoo, Michigan (see episode 1: Plans). He was delighted to see that his award-winning composition for cello “Nocturne,” had been published by Carl Fischer. Also, in that same issue were notices promoting the upcoming Chautauqua tour organized by Loar’s uncle, James L. Loar, for “Fisher Shipp and the Gibsonian Concert Orchestra.”

Lyceum Magazine, Chicago, Illinois, June 1922.

The publication of “Nocturne” heralded what would become a lucrative career in music publishing for Lloyd Loar. However, that would have to wait until his current focus came to fruition. Currently, he was devoted to the perfection of a Gibson Style 5 Mandolin Family of Instruments. It was for this that he spent his days at 225 Parsons Street working as Acoustic Engineer for Gibson Mandolin and Guitar Co.

With mandolins completed, the tour came next. On December 26, 1921, he had written “In 1905 I started out with a concert company and engaged in that profession exclusively until 1920. Since that, part of my time has been devoted to other interests and pursuits.” (Lloyd Loar, “Retrospective,” The Crescendo Magazine, an excerpt from an article slated for publication in the July, 1922 issue). Research in primary source materials confirm his busy concert schedules during the period 1905-1920. We have found records of only one trip away from Kalamazoo between November 1921 and June 1922 and that was to New York and New Jersey in late April.

Passaic Daily News, Passaic, New Jersey, April 21, 1922

A. Kola, teacher/artist/agent for Gibson, Lyndhurst, New Jersey. A German immigrant, after significant world travel, he settled in New Jersey and organized the Kola Mandolin Orchestra. (Crescendo, November, 1922.)

The trip that Loar did undertake during this time of intense focus on mandolin design was to the Guild convention (see episode 7, “The American Guild Convention”). While we have found no record of anyone from Gibson performing at the convention, James H. “Jazz” Johnstone and Loar travelled early to play at a concert with the Kola Mandolin Orchestra at the town hall in Passaic, New Jersey. Loar and Johnstone teamed up with the talented Leora Haight and Walla Zeller to lead the mandolin orchestra arrangements, which must have been a welcome delight for Loar after so may months donning the shop apron.

With the new designs for mandolin completed and/or nearing completion, it was now essential to determine the music that would best showcase them in the concert tour scheduled to begin in one week. There were reports of an obvious mandolin chemistry with Mrs. Haight and Miss Zeller. Would these ladies would be enlisted for the 1922 Gibsonian Concert Orchestra? Both were avid proponents of Gibson instruments. Leora Haight was known to play a 1920s F-4 and had performed to great accolades as First Mandolin in the 1921 Gibsonians, with Albert Bellson, director. (See Episode 1 [photo]) Walla Zeller, mandolin and guitar specialist, had organized the Zeller Mandolin Club in Cleveland, Ohio and was the Gibson artist/teacher/agent there. She scored big at the Guild Convention with her performances and compositions.

Walla Zeller (on left) and Leora Haight; Miss Zeller excelled on guitar, while Mrs. Haight was known for her rapid arpeggios and double-stops. Both composed for classical mandolin.

The program of the concert at Passaic, New Jersey on April 22, 1922 featuring Loar, Johnstone, Haight and Zeller. Cadenza, August, 1922.

Were Haight and Zeller considered for the 1922 Gibsonians? Mrs. Haight had excelled on both mandolin and mandolin banjo with the 1921 Gibsonians and Miss Zeller was a star of the convention. Whatever the process of enlistment may have entailed, and whether or not the extraordinary schedule planned was daunting for these ladies we may never know. One thing remained certain: the 1922 edition would be featuring newly designed instruments and an entertainment of great variety. With Fisher Shipp on her way to Kalamazoo, there would be vocals, skits, comedy and theatrical readings. “Jazz” Johnstone would bring ragtime and jazz. Loar was inviting colleagues to submit compositions and arrangements that would feature marches and waltzes. The artists chosen for 1922 would need versatile skills in all these areas; could not be averse to a gypsy lifestyle; and would need to be free to devote 24 hours a day for entire summer.

“The Gibson Beauty March” presented to Loar by Zahr Myron Bickford at the 22 Guild Convention (Crescendo, July, 1922). The 1922 Gibsonians featured a number of different marches on their tour.

Quite possibly, the most surprising genre added to the repertoire would be the inclusion of traditional African American music. Surely, no one before then had combined the brilliance and precision of the classical mandolin with the wild abandon of the barn dance. Or, had they?

Silas Seth Weeks, ca. 1915. “One of the finest exponents of mandolin in the world.”

“…a revelation in mandolin playing! Mr. Seth S. Weeks is, without a doubt, one of the finest exponents of the mandolin, or perhaps the finest, in the world, and his latest composition, Caprice de Concert, in which passages in double stopping, delicate pizzicato and arpeggio effects, succeed each other, is worthy of the highest praise. Needless to say, the audience applauded this artist to the utmost…” (A review from the Cammeyer Festival, St. James’ Hall, London, 1902. Banjo World, Vol. X, No. 98, p. 34)

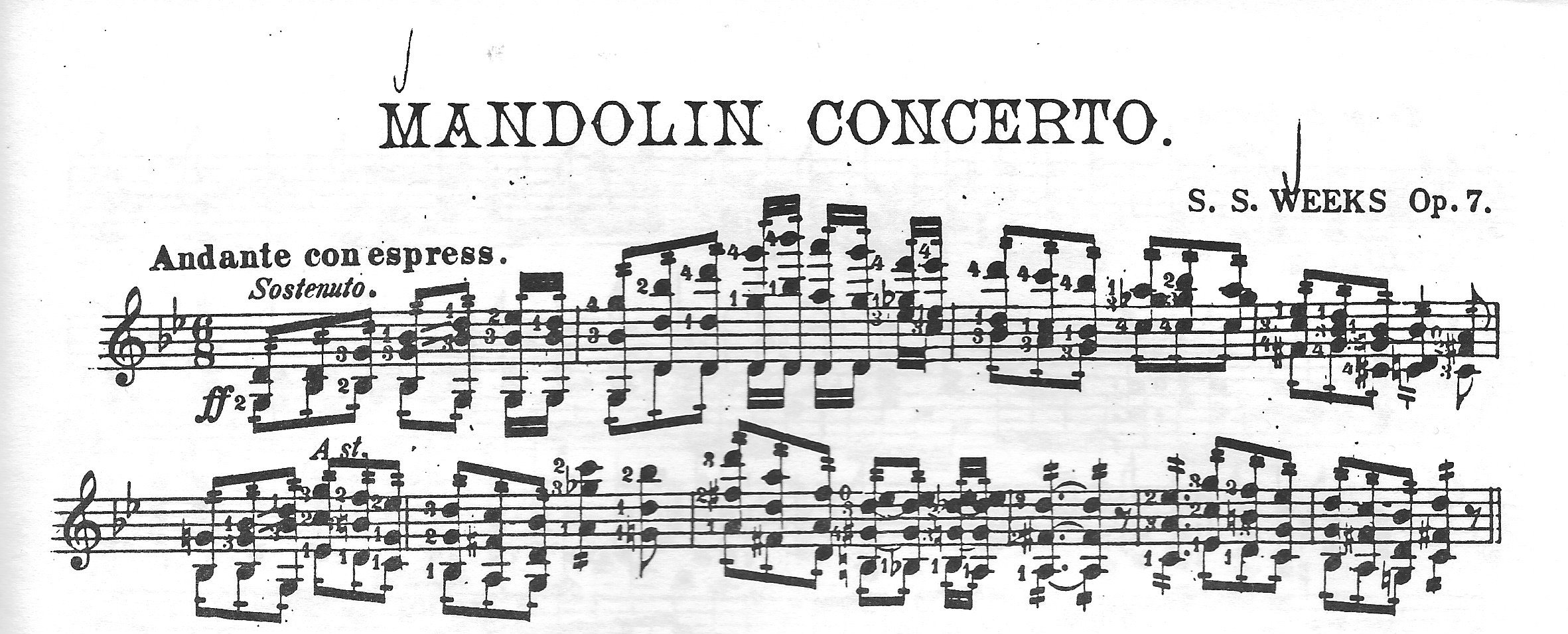

The opening of “Mandolin Concerto” by Silas Weeks. He negotiated challenging triple stops effortlessly on a high quality Brandt mandolin, made in Chicago. Many thanks to Neil Gladd for his article and discography in Mandolin Quarterly, Winter, 1996. We have listened with amazement at the few recordings still extant.

Silas Seth Weeks was born in 1868 in Vermont, Illinois, just 20 miles from Lewiston where Lloyd Loar grew up. The story of his long life and world travels would fill volumes. He was the eighth child of Elenora J. and Thomas B. Weeks. His parents had made their way north from Louisiana in time for Thomas to volunteer for the 28th Illinois Infantry during the Civil War. Afterwards, he opened a barber shop. By the age of 10, Seth Weeks was proficient on violin, guitar, banjo and his favorite, mandolin. In the 1890s, he taught mandolin in Tacoma, Washington, and organized and conducted the Tacoma Mandolin Orchestra. From 1900 until 1914, his travels are relatively well documented with concert notices and reviews, passport and entry permits to England, France, Italy, Belgium, Germany, Russia and the Balkans. He recorded at least a dozen pieces for Edison Bell Cylinders in London; many more of his compositions were released in folios by Shaeffer Music. While his earlier recordings showcase him as “The Paganini of the mandolin,” his later sides include banjo driven songs like “Georgia Camp Meeting” and “Whistling Rufus.” On his concerts, in additional to mandolin solos, he featured banjo duets with Elenora Jones, who later became Mrs. Weeks, .

On July 10, 1903, Weeks’s troop were on tour in Serbia when King Alexander and Queen Draga were assassinated at the palace. Somehow they escaped ahead of the ensuing turmoil that became the Balkan Revolution. As World War I loomed in Europe, he found his way back to the US whereupon he began a stint on the Keith Circuit, playing New York, Providence, Chicago and cities in between. He created an entertainment that ranged from Hungarian Dances to “hoofing.”

Lloyd Loar spent time in Chicago the summer of 1918 working with the Lyceum Bureau to organize Fisher Shipp’s tour without him while he was in Europe, and when he returned from France in the summer of 1919, he took up residence in the windy city. There, Seth Weeks was the toast of the town on mandolin and banjo. Upon witnessing the success of this unique variety of entertainment, it was apparent to Lloyd Loar that the addition of this repertoire would dramatically enliven the program with Fisher Shipp and the Gibsonians.

The Daily National Hotel Reporter, Chicago, Illinois; Aug 10, 1918

Left to Right: Madame Samya, Silas Seth Weeks, Elenora Jones Weeks, “The Hoofer.” Ca. 1918.

In 1920, Seth Weeks resumed touring overseas; in between trips abroad he maintained residences in New York or Boston where he gave private lessons. After his last documented overseas adventure, he was on the “President Harding” as it docked at Ellis Island, returning from France, July 7, 1934. The 1940 census lists him dwelling at 114 W. 12th Street in New York City.

In all those years of a brilliant career, Weeks was never invited to perform at any of the mandolin conventions in the US. Similarly, his photo was omitted from music folios published in the United States where other composers were shown. Why was Weeks not invited to any of the American Guild Conventions?

It would be many years before an African American would enter the front door of the Waldorf Astoria.