Weldon Springs Chautauqua, near Clinton, Illinois. Unlike most summer venues, the resort at Weldon Springs provided a steel-framed concert hall and ample festival facilities. (Dewitt County, Illinois, GenWeb project)

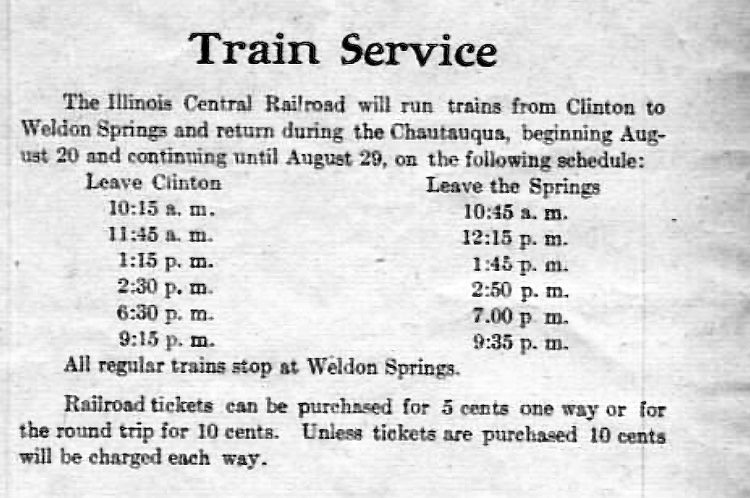

On Thursday morning, August 24th, 1922, in Clinton, Illinois, Wednesday’s heavy rain had subsided. The dark clouds began to allow a hint of morning sun, giving hope to the promise of a beautiful day. After a night in the hotel and breakfast at the diner across the street, Fisher Shipp, Lloyd Loar, Walter Kaye Bauer, Arthur Crookes, Francis Havens and James H. Johnstone boarded the branch line of the Illinois Central Railroad that would take them to Weldon Springs. In addition to their luggage, they stacked a considerable collection of Geib and Schaefer hard-shell cases in the baggage car. A total of at least fifteen instruments ranging in size from mandolin-banjo to mando-bass, the precious cargo included the first Master Models mandolins and Mastertone banjos.

Upon their first arrival at Weldon Springs back in July, Bauer and Crookes, who were experiencing the mid-western United States for the first time, must have been delighted with the expanse of the scenic resort and surprised by the absence of the usual mountain of canvas. In 1901, prominent local citizen Judge Lawrence Weldon had decided to develop his 500-acre fishing camp into a Chautauqua venue. By 1905, they had dispensed with the high-maintenance circus tent and had constructed a steel-framed auditorium, which dominated the hill overlooking the lake. The design? While the interior was based on the original amphitheater in Chautauqua, New York, the Weldon Springs concert hall was a sturdy, permanent version of a traditional Chautauqua tent. It measured 100 feet in diameter with a seating capacity of 5000. As the musicians arrived on this August day, they surveyed a panorama of bustling activity as patrons took advantage of the festival facilities: residential tents (with room for 5 adults or a family with children) dotted the area behind the auditorium; “a grocery (at city rates) sold ice, bread, fresh vegetables, ham, eggs. fresh butter and gasoline;” the Ladies Aid society set up a kitchen with reasonably priced meals, and a very popular popcorn truck made its rounds in the evening. (Dewitt County, Illinois, GenWeb project)

Weldon Springs patrons outside a residential tent that they had most likely rented for the entire week. Many rural families planned their vacations around the Chautauqua.

The design of the interior of the Weldon Springs auditorium was based on the original in Chautauqua, NY.

The Gibsonian Concert Orchestra performed at 3:30 and again at 7:30 that evening. As time for the afternoon program approached, eager attendees crowded the stands as the musicians made their way to the stage. The next morning, both the Clinton Daily Public and the Decatur Herald reported the success of the performance: “Something new in Chautauqua: banjos and mandolins in the hands of experts brings forth unthought of melodies... Through the efforts of Music Master and Gibson Acoustical Engineer Lloyd Loar, they have reached a high degree of efficiency that makes their playing so uniform that the blend of melody is perfect.” (Clinton Daily Public and the Decatur Herald, Friday, August 25, 1922)

By the time those papers hit the stands, the Gibsonians were already making their way to Matoon, Illinois, on a similar schedule. The Master Model mandolins and the Mastertone banjos did the job for which they were designed, filling 5000-seat venues with sound, as was noted in the concert reviews. After accolades about the projection of the orchestra, much was made of the mando-bass played by James H. Johnstone: “It has the qualities of the bass viol, but it is picked instead of bowed.” Further into the set, “the audience is alerted to the tomcat wails turned to melody with musical accompaniment” when Loar applied his violin bow to a common carpenter’s saw. “Listen to the Mockingbird” on the viola was also a hit and Loar’s version of “The Rosary” was so well received in the afternoon he played it again that evening by special request. Fisher Shipp and Walter Kaye Bauer performed a “humorous take-off of the movies in pantomime” in the afternoon and an “equally ludicrous imitation of grand opera” in the evening. Advancing to front center stage, Fisher Shipp “made a real hit” in costume and Italian accent with her original reading, “I Gotta a Rock” while the mandolins’ tremolo evoked the gondolas of old Venezia. The mandolin quintet then displayed that “high degree of efficiency” on many selections. “The banjo ensemble took hold of the audience” with John Phillip Sousa’s “Stars and Stripes Forever.” Having heard this by brass bands during their summer picnic, the audience must have been surprised to hear it “so well performed on such unique instruments!” The evening show concluded with “Miss Shipp and the ensemble in “Sons of Liberty,” a stirring patriotic song written by Lloyd Loar. Miss Shipp was in costume as “Columbia.” (Journal Gazette, Matoon, Illinois, August 26, 1922).

The facilities at Weldon Springs were quite the exception on the mid-western Chautauqua circuit. Most programs were held in canvas tents, but some of those tents were just as expansive as the Weldon Springs auditorium. While the history of the circus tent in America goes back to 1870 when P.T. Barnum took his show on the road, it was the indefatigable actress Sarah Bernhard that pushed the size of the tent to the extreme. During her tour of the United States in 1905, she found the concert halls in the mid-western states woefully inadequate for the crowds that flocked to see her. She realized that rural people were starved for entertainment, and she did not want to lose the sale of a single ticket. She contracted a company in Kansas City, Missouri, to build her a custom tent “with a staggering seating capacity of five thousand. The tent offered a full acre of seating in an area just shy of a football field…and required an attendant army of roadies.” (Peter Rader, “Playing To The Gods,” p. 192). The company was the Fisher Tent Company, and they continued to supply tents for the Chautauqua circuit.

Not all Chautauqua tents in 1922 were erected in remote farmer’s fields. According to the Muscatine Journal, Muscatine, Iowa on July 26, “The huge canvas auditorium was being erected this afternoon on Fourth Street between Cedar and Sycamore Streets. The grounds have been smoothed under the direction of street commissioner E. T. Allen. Shavings have been placed as a floor covering.” On the other hand, the Waterloo Courier of Waterloo, Iowa, on July 8, promises a more bucolic setting: “the real Chautauqua atmosphere will prevail…velvety greensward, cooling shade and a canvas for covering. The Fisher Tent and Awning Co. will furnish the tent. There will be ample seating space, and all who come will be made comfortable.” Along with the tents came the crew who erected and struck the tents and maintained the grounds during the week. There was also a bevy of “Chautauqua Maids,” young ladies hired to attend to any special needs, such as helping the aged and invalid or relieving mothers of wailing babies.

The United States Postal Service issued a stamp in 1974 to commemorate the centennial of the Chautauqua.

The traveling show on the Chautauqua circuit brought entertainment, inspiration and even elucidation to the people of the heartland of American in their “green, golden sheen of grass-grown town lots and its aura of blue-jeans-and-calico neighborliness…” The “talent menus” included famous orators, gifted preachers..., public officials…, concert musicians, singing troupes and occasionally magicians, jugglers and other “exotics.’” (Charles Morrow Wilson, “The Commoner,” p. 266). William Jennings Bryan was the most famous headliner, as evidently many rural mid-westerners responded to his conservative views on such issues as Fundamentalism, Prohibition (strongly in favor) and Darwinism (strongly opposed). However, it seems the musicians preferred the company of Dr. Samuel Parkes Cadman, a liberal clergyman from England who was an outspoken opponent of racial intolerance and anti-semitism. Walter Kaye Bauer recalls enjoying spending time with Dr. Cadman, who was not afraid to follow the arm-waving ravings and booming voice of Mr. Bryan with a little down-to-earth humor.

Walter Kaye Bauer, “A Century of Musical Humor,” Plucked String, 1988, p 42.

By now the ensemble had logged many miles. From tour manager James Loar’s home town of Bloomington, Illinois, on July 7, they had travelled to Alton, Illinois, on the 9th; then by train and automobile through Nebraska and South Dakota, on through southern Canada all the way to Manitou Lake, Saskatchewan. They were back in Leavenworth, Kansas on July 18th, back and forth, to and from Cameron and Moberly, Missouri, on the 19th through the 23rd; back and forth from Davenport and Muscatine, Iowa, all on the same day, July 26th; back to Weldon Springs on the 27th; back to Iowa, Nebraska and South Dakota for the first part of August, and then back for their final visit to Weldon Springs on August 24th. Did these brand new instruments—the “first off the line” Master Models— hold up to the rigors of travel? When Lloyd Loar signed his name to a Master Model label verifying that the instruments had been “tried and tested,” this was no exaggeration.

Manitou Lake, Saskatchewan, Canada, July 1922. Negotiating the roads and rails from South Dakota to Saskatchewan in 1922 was a daunting task that must have tried the mettle of woman, man, machine and mandolin.

Walter Kaye Bauer loved to share his recollections and stories about his long career in show business. Thanks to him, we have a first hand glimpse of the 1922 tour. There were times when destinations required automobiles and carriages to negotiate roads that were little more than wagon paths. However, in 1922, railroads connected most cities, so some journeys were far less rigorous. Nevertheless, even the trains did not aways offer safe conduct. On one occasion, Loar and company had to change trains at 6 pm in Sedalia, Missouri (most likely en route between Cameron and Moberly, around July 22). They stepped off the train to find themselves in the midst of a full-blown labor riot. Disgruntled workers shattered windows and set fires; pandemonium filled the streets.

Bauer was sent to inquire. After a brief explanation, a railroad official said, “there is nothing to worry about, the Texas Rangers have arrived.”

“How many Rangers?” asked Bauer.

The official replied, “two.”

“Only two?”

“Well, it’s only one riot,” replied the railroad man.

Dr. Samuel Parkes Cadman, eminent ecumenical minister of humble origins from Ketley, Shropshire, England, became a well-loved radio personality after moving to America.

Dr. S. Parkes Cadman proved to be a favorite traveling companion of the Gibsonians and a star of many of Bauer’s stories. Most likely en route to Weldon Springs after a performance in Richmond, Indiana, on August 22, Dr. Cadman learned that mid-western hospitality did not always include proper sanitation.

Another headliner that turned out to be good company was humorist Strickland W. Gilliam. According to Bauer, one of Gilliam’s opening observations went like this: “Looking out upon the audience today, I am reminded of the man at the circus who charged 10 cents a head for folks to see his prized Moose. As the line formed, an old man in his eighties came up and held out two dollars. “Its only 10 cents” said the ballyhooer. The old man replied, “this is for me and my children.” Lined up behind him were 19 people, ages 5 to 60. The circus man handed back his money. “Go on in,” he said. “I think the moose would like to see you just as much as you want to see him.”

Next Episode, on September 1: Master Model’s first In-store demonstration and international live broadcast!