The 1924 Gibsonian Concert Orchestra. L to R: Lloyd Allayre Loar; Dorothy Ann Crane; Sallie Fisher Shipp-Loar; James Hart “Jazz” Johnstone; Nellie K VerCies; Eva Lucille Campbell. Instruments, L to R: F-5 mandolin, H-5 mandola, J Mandobass, 10-string MV-5, and K-4 mandocello. Photo from The Rolling Stone, February, 1975.

Welcome to “Breaking News: 1924,” a collection of primary source documents concerning the many facets of the work of Lloyd Loar in 1924, with a focus on the F-5 mandolins, H-5 Mandolas, K-5 Mandocellos and L-5 Guitars, now one hundred years of age.

Gibson F5 75696, signed Lloyd Loar, dated February 18, 1924.

At the dawn of 1924, the entire world took a deep breath to drink in the exuberance that the promise of prosperity brought. In the United States, the deflationary recession that had fueled the labor riots from 1920 to 1922 was almost as far in the rear view mirror as the pandemic and World War I. More and more people had left the rural communities for towns and cities to work in factories where wages were at an all-time high. Free time was a completely new idea for many Americans, but most embraced it completely. Automobiles crowded the woefully inadequate highways and city streets: over 20 million automobiles were on the road by the end of the decade. In the White House, Calvin Coolidge and his secretary of commerce Herbert Hoover led a Republican administration that championed big business and cultivated captains of industry, while turning a blind eye to wild speculation by investors who bought on margins in a stock market on a collision course toward disaster. It was election year, and even though Coolidge had inherited the stigma of the Teapot Dome scandal from the Harding administration, the Democratic party was split apart on issues like immigration and prohibition and offered no challenge to the Republican ticket. The so-called “Flaming Youth” crowded the speakeasies at night, dancing the Charleston to Jazz music. Young men were often seen driving wildly in convertible automobiles with a flasks of gin in their pockets and short haired, short skirted “Flappers” squeezed in around them. The musical instrument of choice to bring along for such outings? As was the case for P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster, there was nothing more appropriate than a banjolele.

Stylish ladies out on the town in 1924 carrying washboard for percussion (left), “jaw” harp and banjolele (middle) and concertina (on right)

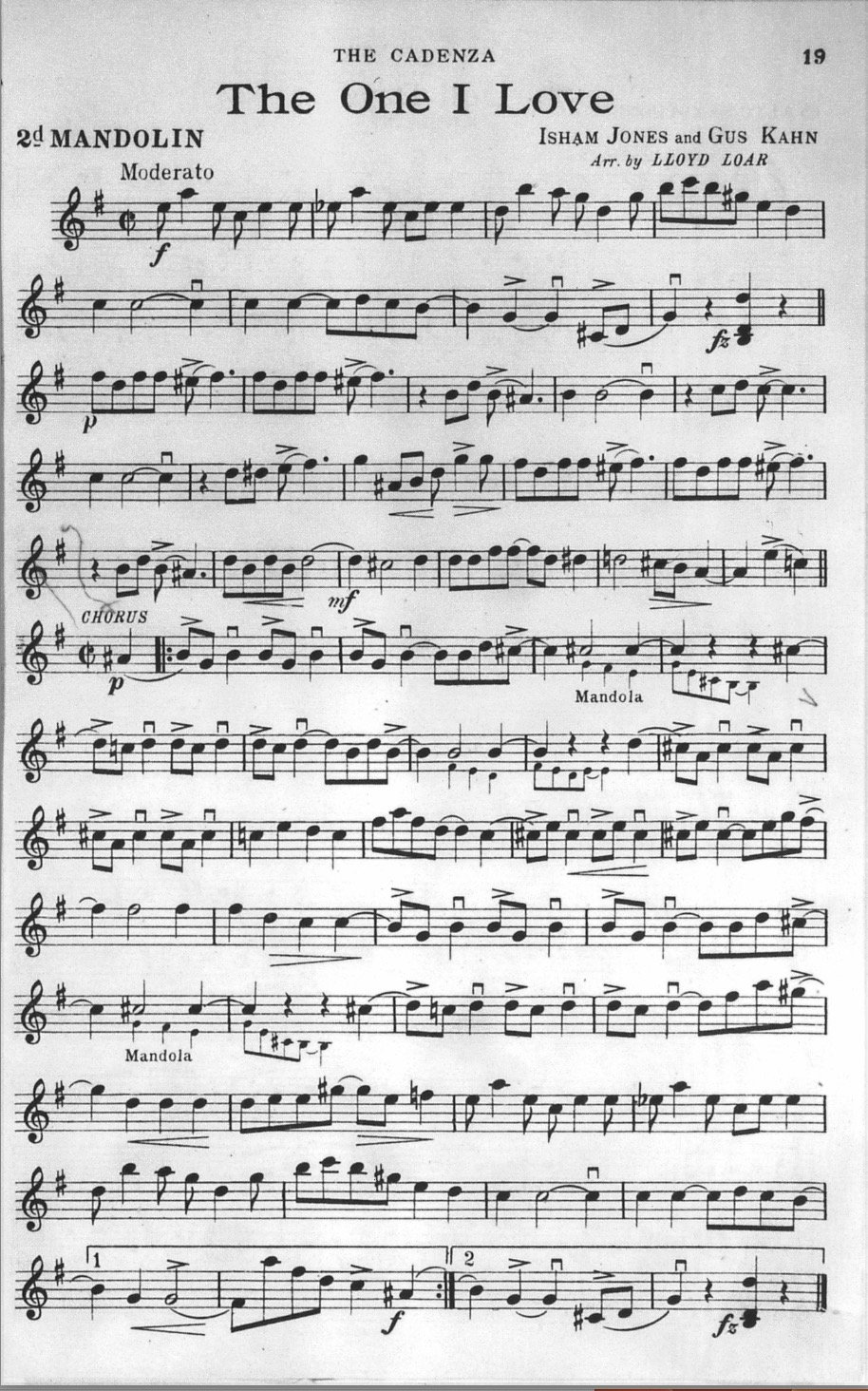

Many homes now had radio sets (sales of radios went from 60 million in 1922 to 850 million by the end of the decade), and the phonograph had found a significant place in many lives. “Popular music” was now a commodity rated by airplay and record sales, and, at a precedent that followed popular music thoughout the rest of the century, the raucous, raw music of artists who had abandoned convention gave way to smoother melodies and harmonies and rhythms more palatable to the general public. There were rare exceptions, such as Bessie Smith’s “Downhearted Blues,” which hit number one in 1923. In 1924, the Isham Jones Orchestra featuring Al Jolson (on vocals) held the number two spot with “California Here I Come” and “It Had To Be You” at number four. In addition to Jones’ big-band instrumentation that included a full complement of brass, strings and rhythm sections, the Orchestra carried a mandolin and banjo string section which was featured on some of the repertoire including “The One I Love.” Isham Jones was a Gibson endorser, and the talented multi-instrumentalists he employed were among the best paid side-men of that era; Charles McNeil, the banjoist, for example, reported an income of $150 per week during 1924. The music for the mandolin quartet was arranged by Lloyd Loar, and we have included that entire arrangement at the end of this episode.

The Isham Jones Orchestra performed on Master Model Instruments as part of their repertoire. Despite the poor quality of this magazine photo, we make out an F5, H5, TB-5 and possibly an MB-5. Later, the L-4 guitar was replaced with an L5. Cadenza, February, 1924.

The Crescendo, February, 1924.

For Lloyd Loar, this was a year of significant transition. By January of 1924, his title at Gibson had been increased to “Superintendent and Acoustic Engineer,” and later, “Factory Manager and Acoustic Engineer,” with managerial and sales responsibilities added to the duties agreed upon in 1921. Loar was tasked with research and development, supervision of construction, travel and performance, mentoring Gibson agents, head of the Department of Repair and, as we have seen, arranging and publishing music to promote Gibson instruments. Another of his efforts came to national attention when both the Music Trade Review and The Cadenza magazines published articles about the new Gibson catalog “N,” with color illustrations of the Master Models. Advertising manager Clifford V. Buttelman (who was leaving Gibson for Melody magazine), Loar and production manager D. C. Mafit prepared this 60-page masterpiece of Gibson advertisement a few months before (See Breaking News: 1923, Money Over Melody).

Cadenza, January, 1924.

In January of 1924, the Gibson factory was in full swing with the Master Model project. Was there a mandate for production, to move all unfinished instruments on through? We have identified three batches of style 5 that were stamped in the last few months of 1923, over 100 of which were signed and dated February 18th and March 31st of 1924. Those were the largest number of instruments ever assigned to a given day. Then, after a lapse in Master Model production that continued until October, most of the remainder of those batches were signed in the last three months of the year. A few from the last batch did not receive signature labels, but in all other aspects, they clearly exhibit the features and appointments of the Loar signed instruments. All those instruments signed from 1922 through the end of 1924 are unique in appointments, features and sound, and are quite different from later models.

Factory Order Number from Gibson F-5 81290, the last stamp number of the Loar F5. On this mandolin, all appointments are identical to the the F-5s dated December 1, 1924, but there was no signature label affixed over the stamp number We know this was stamped at the end of 1923 because beginning in 1924, an “A” suffix appeared on the stamp numbers.

By March of 1924, Harry Ferris, the General Manager of Gibson announced a new nationwide campaign to promote Gibson instruments in magazines and newspapers across the country. However, in a curious move that we find unfathomable considering the number of F5s being built, references to the Master Model line and the F5 disappeared everywhere except in the Gibson catalog. Clearly, competing in the booming banjo market was an important consideration, but even beyond that, the heavy push in advertising was geared toward everything except the Master Model. In some instances, some of the language associated with Loar’s efforts was repeated, such as Stradivarius graduations, but the accompanying illustrations depicted the F-4 or even the style O guitar.

Vernon Parish Democrat, Leesville, Louisiana, January 10, 1924

Music Trade Review, March 8, 1924.

Despite leaving behind the Master Models in magazine ads, Gibson continued to promote the Virzi Tone Producer, and even began a line of Gibson violins, actually made by the Virzi Brothers in New York. Cadenza, January 1924.

Loar’s personal relationship with Sallie Fisher Shipp-Loar, his wife since 1916 and musical partner since 1906, suffered a serious strain during his time at Gibson. They had had not lived together full-time since leaving the boarding house at 1522 53rd Street in Chicago, Illinois, where they had moved when Loar returned from Europe in 1919. They left Chicago in 1920, and from 1920 through much of 1923, Loar lived in two rooms at a boarding house on 216 South Park Street in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and Shipp lived with her mother in Brookfield, Missouri. She traveled to meet him for rehearsals in Kalamazoo and to join the entourage en route for performance tours, and he made occasional trips to Brookfield. During the summer of 1923, the offers of Lyceum work that had made Shipp a star on the Chautauqua circuit had dwindled dramatically. Many venues now featured camp meetings with fire-and-brimstone preachers like Billy Sunday, a former baseball star whose ecstatic remonstrations from the pulpit whipped his crowd into a frenzy. Some Chautauqua arenas were even usurped by the Ku Klux Klan (see Breaking News 1923, Episode 9). In her effort to rekindle her stardom, in 1923 Shipp had insisted on returning to her instrumentation (piano, violin and mandolin instead of full mandolin quintet) of the previous decade. That year, Lyceum concert bills advertised her group as “The Fisher Shipp Orchestra,” even though Loar performed with her. Conversely, the Gibson concerts advertised “The Gibsonian Concert Orchestra with Lloyd Loar” and did not mention or show photographs of Shipp in their advertisements. Even though Lloyd Loar’s uncle, James Loar of Bloomington, Illinois, continued to be “General Manager, International Chautauquas,” Loar and Shipp were booked on less than a dozen of those venues in 1923 and none in 1924. Compared to 105 performances in 1922, this must have been alarming for her. In 1924, Loar welcomed Shipp back to the bill with the Gibsonians. In addition, and for the first time, she posed in a group photo to promote their performances. In late 1923, Lloyd Loar moved into the house at 720 Kalamazoo Ave, Kalamazoo, Michigan, where his teaching studios were located, and perhaps engaged his wife as teacher of piano and voice. For the first time since 1920, the couple was sharing an address. Shipp still spent much time traveling to visit her mother, but the language in newspaper accounts began to refer to “her home in Kalamazoo.” We are able to track their movements thanks to frequent notices in the society pages of the Linn County Missouri newspapers; we do not feel we are straying too far into conjecture to assume those movements gave insight as to when Loar focused on Gibson work, performance duties and personal matters.

Fisher Shipp-Loar and Lloyd Loar. The Lima News and Times Democrat, May 25, 1924

During the course of this year, we look forward to publishing many of the documents we have collected. For now, here is an outline, with quotations from primary sources, that answers the question we posed at the end of Breaking News 1923: “Where was Loar in ‘24?”

October, 1923: Loar moves out of the boarding house at 216 S Park Street to a house at 720 Kalamazoo Ave, Kalamazoo. Downstairs, Loar led a team of teachers providing lessons as the “National Music Studio.” (Kalamazoo City Directory, 1924; Daily News, New York City, October 20, 1921)

January 7, 1924: One H-5 Mandola receives Master Model Label signed Lloyd Loar, dated January 7, 1924.

January 25, 1924. “Gibson, Inc., issues new catalog.” “Lloyd Loar, superintendent and acoustical engineer, and D. C. Mafitt, former advertising manager…(prepared the) technical copy…” Music Trade Review, February 2, 1924. Cadenza, January, m1924.

Feb 1, 1924: “Mrs. A. D. Shipp entertained the Better Yet Class of the Christian Church…assisted by (her daughter) Mrs. Fisher Shipp-Loar.” Linn County Daily Budget, Brookfield, Missouri, Feb 1, 1924.

Feb. 2 & 3: Loar invites Gibson stenographers Nell VerCies, Dorothy Crane and Lucille Campbell, all in their early 20s and members of The Gibson Melody Maids, to join the 1924 edition of the The Gibsonian Concert Orchestra. Fisher Shipp-Loar attends rehearsals in Kalamazoo, and the group posed for photos at James H. Johnstone studio.

Feb 4: “Mrs. Fisher Shipp-Loar has returned from Kalamazoo, Michigan after visiting her husband.” The Daily Argus, Brookfield, Missouri, Feb 4, 1924

February 11: One K-5 mando-cello receives Master Model Label signed Lloyd Loar, dated February 11, 1924.

February 13: One L-5 guitar receives Master Model Label signed Lloyd Loar, dated February 11, 1924.

February 18: At least Forty-six F-5 mandolins receive Master Model Labels signed Lloyd Loar, dated February 18, 1924.

February 19: Lloyd Loar receives 94 shares of Gibson stock dated February 18, 1924.

March 24, 1924: At least three F-5s receive Master Model Labels signed Lloyd Loar, dated March 31, 1924.

March 31, 1924: The largest signature date with at least 64 instruments (36 F-5 mandolins, 14 H-5 mandolas, three K-5 mando-cellos and 11 L-5 guitars) known to have received Master Model Labels signed Lloyd Loar, dated March 31, 1924.

April 3: “Mrs. Fisher Shipp-Loar has returned from from Kalamazoo and is visiting her mother, Mrs. A. D. Shipp.” Daily Argus, April 3, 1924.

April 12: “Mrs. Fisher Shipp Loar returned from Linneus.” Linn County Daily Budget, April 12, 1924

May through June, 1924, The Gibsonian Orchestra tours Northeast and Midwest.

May 11, 12 & 13: Fisher Shipp, Lloyd Loar and the Gibsonian Orchestra perform at the American Guild Convention. The grand finale concert held at Carnegie Music Hall…in Pittsburg, PA. Various sources including The Gazette Times, Lima, Ohio. May 12, 1924

May 22, 1924: “Fisher Shipp and the Gibsonian Concert Orchestra to perform at Memorial Hall in Lima, Ohio, on May 28.” Lima Republican Gazette, May 22, 1924; The Lima News and Times, Democrat, May 25, 1924

June 7, 1924: Fisher Shipp and the Gibsonian Concert Orchestra to perform at Woodhaven Church, The Chat, Brooklyn, New York, June 7, 1924

July 19: Mrs. Fisher Shipp-Loar and her mother, Mrs. A. D. Shipp leave for Kalamazoo to spend two weeks with the former’s husband, Mr. Loar.” The Daily Argus, July 19, 1924.

August 7, 1924 “Lloyd Loar, Factory Mgr., Gibson, Inc.” endorses Grover. Music Trade, August 7, 1924.

August 14: “Mrs. Fisher Shipp-Loar has returned from Kalamazoo, Michigan.” Linn County Daily Budget, Aug 14, 1924

Sept 3: “Mrs. Fisher Shipp-Loar performs at Rotary Club Banquet.” The Daily Argus, Sept 3, 1924

Sept 17, 1924: Hart replaces Ferris as General Manager at Gibson, Inc., Advertising Manager Stewart resigns. Music Trade, September 20, 1924.

September 18: At least three F-5 mandolins signed Lloyd Loar, dated September 18, 1924.

September 22: At least two F-5 mandolins signed Lloyd Loar, dated September 22, 1924.

Sept 24: “Mrs. Fisher Shipp-Loar will leave today for her home in Kalamazoo, Michigan, after spending the summer with her mother, Mrs. A. D. Shipp.” The Daily Argus, Sept 24, 1924

October 7, 1924: Mrs. Fisher Shipp Loar is visiting her mother, Mrs. A. D. Shipp. The Daily Argus, Oct 7, 1924

October 7, 1924: At least six H-5 mandolas signed Lloyd Loar, dated October 7, 1924.

October 10: “Fisher Shipp travels from Kalamazoo to Brookfield to visit her mother” Brookfield Gazette, Brookfield, Missouri, October 10, 1924

October 13, 1924: At least three K-5 mando-cellos signed Lloyd Loar, dated September 18, 1924.

October 14: “Lloyd Loar, acoustical engineer for Gibson, Inc., … designer of the Tenor Lute” Music Trade Report, October 19, 1924.

October 17, 1924: Loar signs an agreement with Guy Hart receiving “final payment on all patent contracts and royalties.” (Roger Siminoff, “The Life and work of Lloyd Allayre Loar” p. 65 & 66.)

Oct 18: Mrs. Fisher Shipp-Loar performed at Christian church. The Daily Argus, October 18, 1924

Oct 19: Article appears in the Kalamazoo Gazette: “Lloyd Loar Accepts Musical Post / … will leave early in December for Boston where he will be associated with Walter Jacobs (Melody Magazine)…in his association with the Gibson Company he has been factory manager and acoustic engineer. He will continue his association with that concern after he leaves for Boston in an advisory capacity.” The Kalamazoo Gazette, Kalamazoo, Michigan, published October 19 and 25th.

October 28. An article similar to the Kalamazoo article of Nov. 19 & 25:: “Accepts Musical Post / Lloyd Loar and wife, Mrs. Fisher Shipp-Loar to Boston” The text includes “will leave early in December.” The Daily Argus, Brookfield, Missouri, October 28, 1924.

November issue of Crescendo: Lloyd Loar’s close friend William Place, Jr., encourages students to write to “Lloyd Loar, c/o Gibson, Inc., Kalamazoo, Michigan.”

November 15, 1924 “Lloyd Loar, Factory Mgr., Gibson, Inc.” endorses Grover. Music Trade, November 15, 1924.

November 13: Lloyd Loar performs a duet with Mrs. Ivan Rasmussen, First Presbyterian church, Kalamazoo, Michigan (Rally for Charity Drive) Kalamazoo Gazette, Nov 11, 1924.

November 17, 1924. At least one F-5 mandolin and one L-5 guitar signed Lloyd Loar, dated November 17, 1924.

November 24, 1924 “Mr. Lloyd Loar, M. M. Engineer” (Master of Music) named as one of the judges for Crescendo’s musical composition contest. The Crescendo, November, 1924.

December 1, 1924. At least 11 F-5s and 11 L-5s known to have Master Model Labels signed Lloyd Loar, dated December 1, 1924. At least 30 instruments were finished from the 11985 FON batch, the last stamp date in late 1923; some did not receive a signature label.

Dec 20 (Saturday) “Mr and Mrs. Loar will provide special music for the Christmas sermon 6:30-7:30.” (Christian Church, Brookfield) Linn County Daily Budget, Dec 20, 1924.

December 22, 1924 (Monday): “George Altermatt made factory manager of Gibson, Inc., Kalamazoo, Michigan” replacing Lloyd Loar. Music Trade, Dec 27, 1924.

Dec 23 (Tuesday) “The musical program was put on by Mr. and Mrs. Loar.” (Brookfield Rotary) Linn County Daily Budget, Dec 24 1924

December 23: Mr. and Mrs. Loar perform for the Rotary Club luncheon. The Daily Argus, Dec 23, 1924

December 23: Mr. and Mrs. Loar perform 6:30-7:30 pm in Linneus, Missouri. Linn County News, Dec 23, 1924.

December 25, 1924: “Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd Loar are enjoying a Christmas dinner and family reunion at the home of Mrs. A. D. Shipp.” The Bulletin, Linneus, Missouri. Dec 25, 1924

December 26, 1924: Loar returns to Kalamazoo.

December 27, 1924: “Mrs Fisher Shipp-Loar left today for Kalamazoo, Michigan to join Mr. Loar. From there, they will go to their new home in Boston, Massachusetts. Linn County Budget, December 27, 1924

December 27-31, 1924: Loar moves out of the house at Kalamazoo Ave.

January, 1925: Mr. and Mrs. Loar move into the house at 88 Corey Ave, WR, Boston, Mass.

As a bonus: Lloyd Loar’s mandolin quintet arrangement of Isham Jones’ popular song, “The One I Love.”

Isham Jones’ Brunswick recording of “The One I Love,” featuring Al Jolson. Due to the recording techniques of the time, the mandolin ensemble is virtually inaudible, lost to the brass and rhythm instruments.

Stay tuned for our next episode, the biggest day yet of the F5: February 18, 1924!!