During the first months of 1924, there must have been quite a roar of activity in the Gibson workshops. By March 31, 1924, they had produced the largest number of Gibson Master Model instruments ever assigned to a single date; and of course each label was signed by acoustic engineer Lloyd Loar. Thanks to Dan Beimborn’s Mandolin Archive and Darryl Wolfe’s F-5 Journal, as well as our own studies, we can report at least 64 Master Model instruments: 36 F-5 mandolins, 3 K-5 MandoCellos, 11 L-5 Guitars and 14 H-5 Mandolas. Of the known F-5 mandolins, 20 had flowerpot peghead inlays and 16 had the non-typical fern inlay pattern (see photo above); all but one Mandola had the fern inlay peghead. We find that a significant number of these instruments left the factory with a Virzi Tone Producer installed. Approximately half way through the sequential order of these mandolins, and possibly associated with the fern inlay, the previously specified grained ivoroid body binding was replaced with white plastic and the finish was scraped off the binding. This resulted in an improved visual contrast. Today we can recognize the distinctive outline that makes these instrument stand out, even in the old photos. The caps of the body points remained grained ivoroid. This protocol continued on F-5s through the “fern” (post-Loar) era. Additionally, most of the Fern-Loars we have seen came with the silk-plush green lined Geib and Schaefer case (see margin scroll), while many of the flowerpot models from 1924 were shipped in the G & S case with red velour. Quite clearly, the Fern-Loars were meant to be something new, different and spectacular.

Gibson F-5 76553, March 31, 1924. Fern inlay, white body binding. A pristine, completely original example.

Gibson F-5 75950, March 31, 1924: flower-pot inlay, ivoroid body binding and red-lined G & S case.

Gibson F-5 75950 in original case.

Left: floor inlay design in the Baptistery of the Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence, Italy, 1029. Middle, flower-pot inlay F-5 75950, right fern inlay, 76553, both dated March 31, 1924. The decorative genius of the old world often shows up on Gibson instruments.

Labels in the Gibson F-5 75947, dated March 31, 1924. Notice the serial number label is in the distinctive hand that we have seen since the beginning of our examination of the F-5. “Lloyd Loar” is signed and dated in the very familiar style throughout this signature date.

Labels in Gibson F-5 75941. The serial number label is written in a different, much cruder style. We begin seeing this more in the F-5s in 1924.

Despite the frenzy of production in early 1924, creativity was at its peak. From woodworkers to finishers, they focused on the highest quality. The team under Loar at Gibson was making magic with materials at hand, and innovation was part of that mindset, not just with the Fern-Loar. For example, throughout the entire production of the Master Model project, finishes were darker and richer, and in a curious parallel to the color, the sound of these instruments is darker and richer. Within that general assessment of tonality, we have observed an endless variety of tone color, complexity and nuance. The installation of the Virzi Tone Producer had become more refined and tonal results in some the Virzi mandolins, such as 76553, the Ada Merrifield F-5, are quite stunning.

Perhaps Lloyd Loar was focussed on the Gibson showcase at the upcoming Guild Convention in Pittsburgh in April and was responding to some of the feedback from the two previous conventions. Ostensibly, there would be a huge opportunity to present these instruments, and additional acceptance and sales would support Loar’s financial relevance to Gibson, Inc. Judging by the subsequent appearances of style 5 instruments in the mandolin organizations of western Pennsylvania after 1924, and the number of F-5s from that area that surfaced during the Bluegrass revival of the 1960s-90s, one might conclude that this plan was well conceived and productive.

Music Trade Report, March 8, 1924: Harry Ferris’ new promotion campaign.

However, at the same time that the workshop was outputting more Master Model instruments than ever, General Manager Harry Ferris’ plan to create Gibson Franchises focused on anything but the F-5. Ferris wanted to authorize exclusive Gibson dealerships and phase out the teacher/student/agent system that had been a hallmark of Gibson’s sales strategy from the beginning. Most of the newly ordained franchise music stores catered to a more general audience who would be more likely to purchase much less expensive models than the F-5. Only the Gibson catalog still promoted Loar’s efforts. The only Gibson advertisement in a music magazine in 1924 that we have been able to locate was in the “page 19” articles in The Crescendo, but even there, there was no mention of the F-5. It seems Ferris put responsibility for advertisement in the hands of the new Gibson dealers, many of whom placed ads at their own expense in local newspapers. The media blitz that had heralded “The World Hears A New Tone” in 1923 disappeared completely in 1924. Consequently, the March F-5s were slow to find homes. We have no sales records to confirm when each of these Loar signed instruments was shipped, but we have evidence that some did not find homes until years later. In a March madness where the head doesn’t talk to the hands, the front office and the factory seem to have been woefully out of touch.

Ironically, at the same time that C.V. Buttelman, the former advertising executive at Gibson, was receiving accolades for putting together the Gibson catalog “N,” he left the company for Boston and began his new job with Melody magazine, officially beginning on February 1, 1924.

The Crescendo, March 1924, p. 10.

At the same time the front office began turning its back on Lloyd Loar, mandolin organizations across the country began to feature more and more Master Models in their enembles.

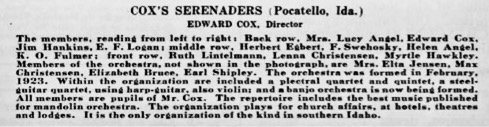

Cox’s Serenaders, the cover photo of The Crescendo, March, 1924.

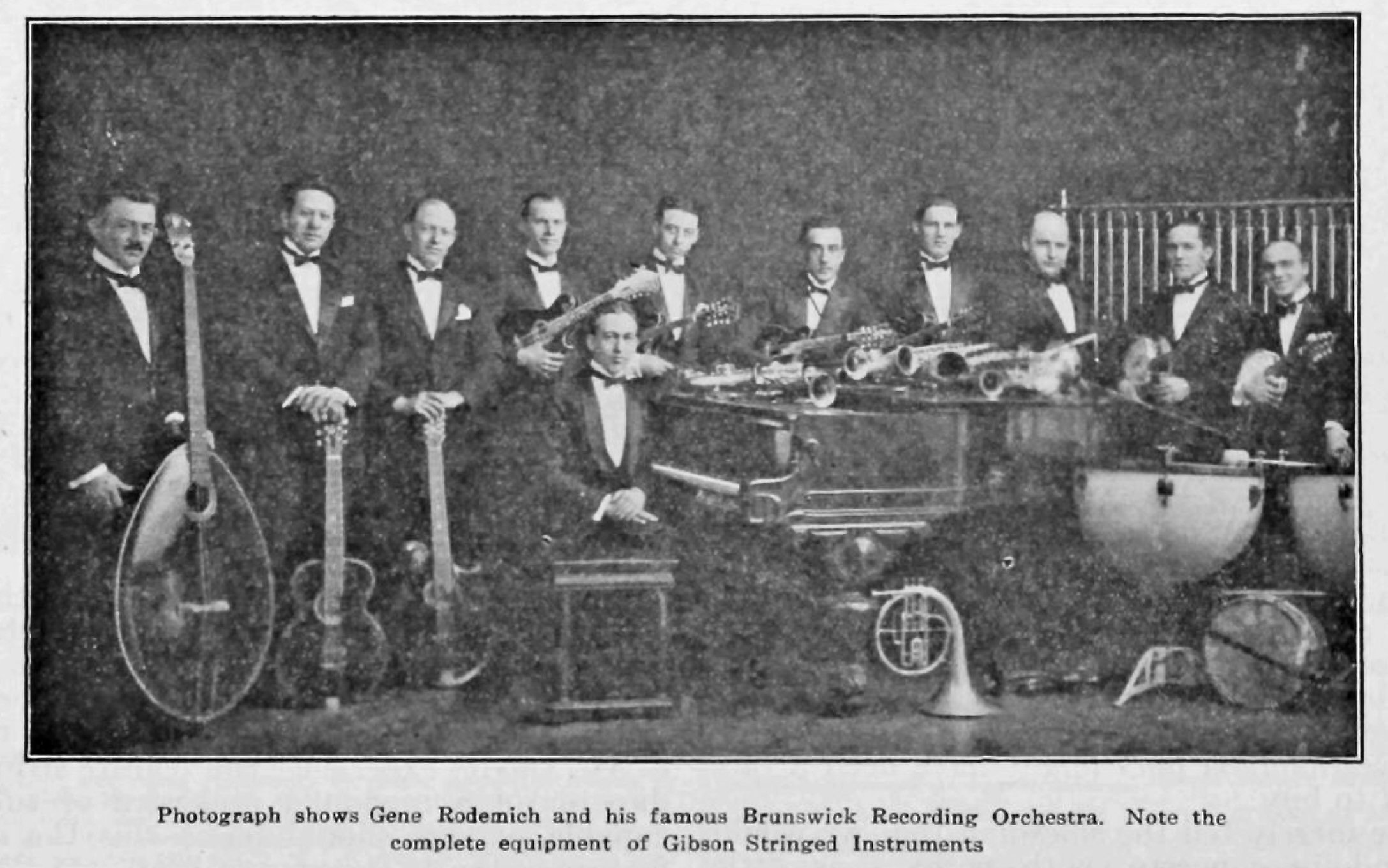

Gene Rodemich and The Brunswick Recording Orchestra included two F-5s and an H-4. Crescendo, April 1924.

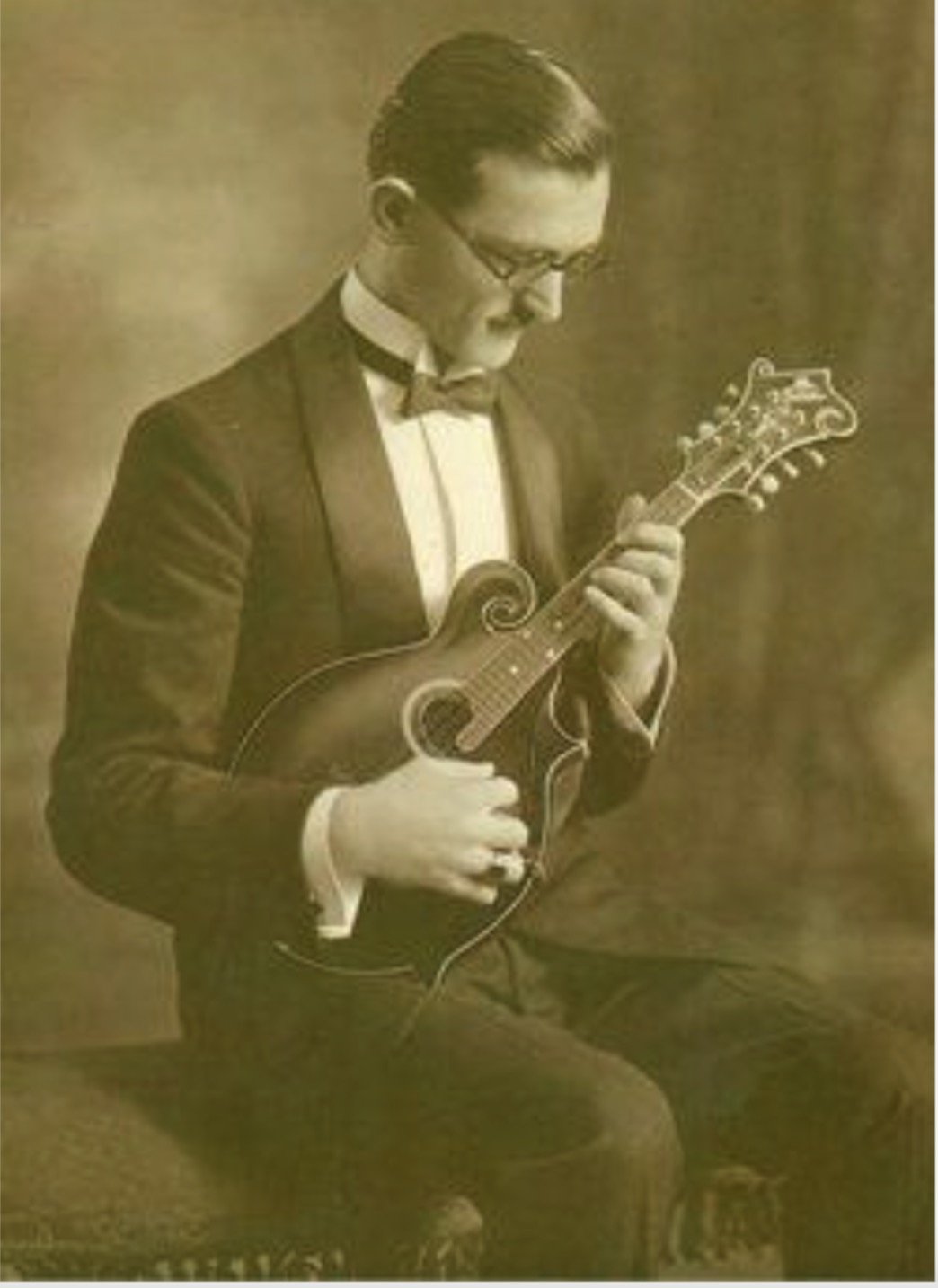

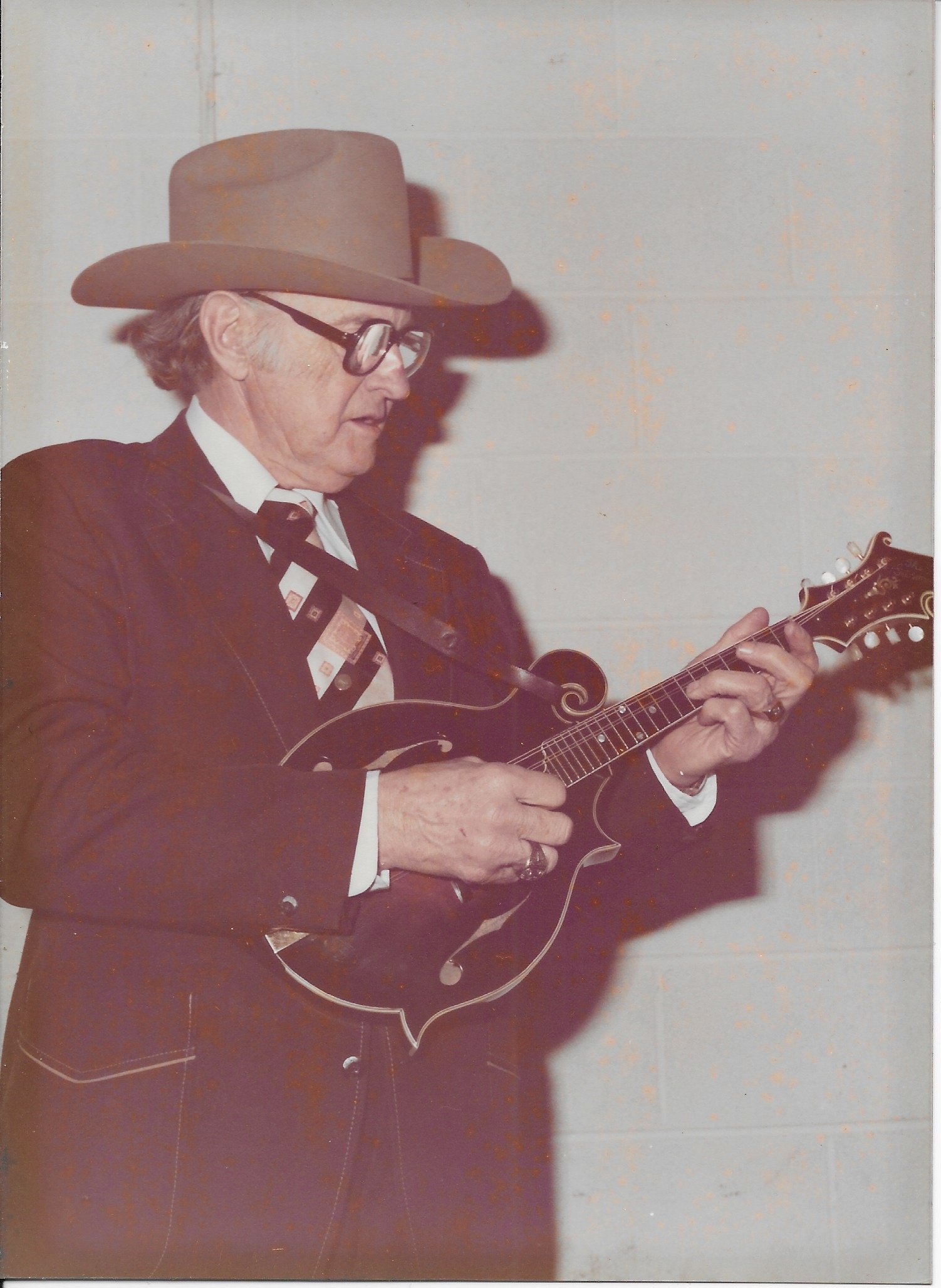

Original owners of March 31st, 1924 F-5s: left, Mrs. Ada Merrifield, Gibson Catalog Q, p. 18. Paul Lieber, Crescendo, August, 1926; T. A. Miles, Knoxville, Tennessee, with F-5 #75947.

Mrs. Ada Merrifield, Paul Lieber, Herman F. Torro, T. A. Miles, Adolph Regnald, Vladimir Lukashuk, Charles Carter, Eugene Claycomb, Hermon Von Bernewitz and Conrad Gebelein were among the first generation of owners of Loar-signed instruments with the date of March 31, 1924. We have no records as to when they all acquired these mandolins, but for example, Mrs. Ada Merrifield from Willimantic, Connecticut, bought her “new” March 31st, 1924 F-5 from her teacher, Walter K Bauer, in 1927. By 1928, Mrs. Merrifield had an F-5 and H-5; Paul Lieber of Bloomington, Illinois had a full set of Master Models: two F-5s, an H5, L5 and a K5. He was quoted: “music will once again turn to mandolin and guitar. ” It was Mr. Gebelein, however, that single-handedly populated the Chesapeake Bay State with F-5s, H-5s and K-5s.

Conrad Gebelein with his Loar era F-4. Although he was responsible for putting many Master Model instruments into the hands of players, he was more likely to be seen with a conductor’s baton.

Conrad Gebelein, born in Fuerth, Germany on December 7, 1884, had begun working in a musical instrument repair shop near Nürnberg at the age of nine in order to earn money for music lessons. He and his sister left for the United States in 1910, landing in Baltimore, Maryland on the ship “Nectar” on November 9. Working as a musician for hire, he managed to finance his education at the Peabody Conservatory. He attended classes by day, played banjo in speakeasies at night and piano at weddings and churches on weekends. An enterprising young man with an entrepreneurial spirit, he gave private and group mandolin lessons and soon became a Gibson Teacher-Agent. By 1920, he was distributing a significant number of Gibson mandolin family instruments, tenor banjos and Hawaiian instruments in the Baltimore area. In 1921 he became music director at Johns Hopkins University and founded the Johns Hopkins Marching Band, which he directed until his retirement in 1971. “Gebby” was a much loved figure at that University: he not only led the band at sporting events but was often seen arguing heatedly with referees at the LaCrosse games.

The Silvertone Serenaders, The Crescendo, June, 1926. Front row seated, left to right: Mrs. Anna Smallwood, John Hayes, Elizabeth Hubbel. Standing left to right: George Sandlars, Henry Dall, Joseph Ruppel, Duane Hayes, Joseph Rupplein, Charles Wolf, Henry Kaiser, Conrad Gebelein, director.

Gebelein organized several different musical aggregations including the Silvertone Mandolin Club, The Hawaiian Troupe and the Johns Hopkins Banjo Club. On November 12, 1925, his newly created Baltimore Mandolin Orchestra performed a live concert broadcast on WBAL radio, led by Gebelein’s baton and mandolin solos.

Baltimore Sun, November 12, 1925.

After 1924, aside from his commitment to Johns Hopkins University, Mr. Gebelein focused his efforts on the Baltimore Mandolin Orchestra. He also worked to fill the chairs with Gibson instruments; some were purchased for the orchestra and some were sold to members of the orchestra through “Gebelein Music.” In photos on the Baltimore Mandolin Orchestra website as well as in the Gibson catalogs and Crescendo magazines, we see many different Loars, and a few can be identified: From the March 31st group, F-5 #76780 & F-5 75941 mandolins, H-5 Mandola 76498; and K-5 MandoCello 76981 (which was signed October 13, 1924).

Baltimore Mandolin Orchestra, ca. 1928. At least two F-5s, 1 H-5 and 2 K-5s! Mr. Gebelein, standing, back row right;

Gibson F-5 76780, Photo by Phil Cooley. This mandolin occupied the first chair with the Baltimore Mandolin Orchestra for 98 years, often seen in the hands of soloist Joyce Adams. Today, it is in the very capable hands of Michael Schroeder of the Louisville Mandolin Orchestra.

Gibson F-5 75941, signed by Lloyd Loar and dated March 31st, 1924, one of the darkest in tone and color.

We have no record of exactly when Gibson F-5 #75941 left the factory, but we know it was purchased through Gebelein Music and was in use in the orchestra; when the orchestra was forced into hiatus during World War II, it was purchased by one of the orchestra members, Joe Murphy, from Washington, D. C. In the 1960s, Murphy traded it to Charles Barnes of Vermont. Courtesy of George Gruhn and Harry Sparks, Barnes passed it on to Tony Williamson in December, 1977. It has been played by Williamson as his primary mandolin since that time and has made appearances in each of the continental United States, Hawaii, Japan, Taiwan, Italy, France, Spain, Germany and England. Since 1977, maintenance has been performed by either Randy Wood, Steve Gilchrist or Lynn Dudenbostel. During Williamson’s long tenure with the mandolin there have been occasions when 75941 was played by Bill Monroe, Jethro Burns and David Grisman.

Bill Monroe plays Gibson F-5 75941, circa 1985. Photo by Mike Mendenhall.

Did David Apollon, the “mad maestro of the mandolin,” also play 76780 and 75941? He was one of the stars of a musical show in Washington, D.C. for the entire week leading up to December 7, 1941. Gebelein and Murphy were undoubtedly in the audience, for Apollon’s dedication to them on two promotional photos are dated from that time. We cannot help but wonder if some of the Baltimore instruments may have actually found their way into the hands of that master at some point during that week. It must have been a tremendously exciting week, and, in retrospect, a poignant prelude to the disaster and ensuing war that would change life dramatically for these musicians.

Evening Star, Washington, D. C., December 6, 1941_

Dave Apollon autographed photos to both Conrad Gebelein and Joe Murphy. Photo, left, “to Gebby-” Baltimore Mandolin Orchestra website gallery; photo on right, “to Joe Murphy,” courtesy Tom Isenhour collection.

Prior to World War II, and resuming afterwards, Gebelein and members of the orchestra put their instruments to constant use, and they all bear the strong voice associated with much playing time. When repair became necessary, Gebelein relied on the Gibson factory. Thanks to curator and appraiser Joe Spann of Gruhn Guitars and author of “Spann’s Guide to Gibson,” we have received the following notes from Gibson shipping ledgers (it is our understanding that such records prior to 1935 are not extant):

“1924 Gibson F-5 (serial number 75941)-factory repaired. Returned to C. Geberlein (sic) Music on 15 June 1936.”

“1924 Gibson F-5 (serial number 76780)-factory repaired. Returned on February 27th 1942 to Conrad Geiblen (sic)”

We do not know if Mr. Gebelein ordered the Virzi Tone Producer removed, but in both mandolins there is clear evidence of factory installation and removal. Aside from that, the primary matters of concern were wear on frets and function of tuners. At the time, Gibson’s protocol for fret wear was to replace the entire fingerboard. Whereas 75941 currently has a fingerboard with dot inlay and binding consistent with factory specification for 1936, we can suspect that installed during the repair documented above; Similarly, since pearl block position markers were factory specifications on style 5 models by 1942, we can also assumes that the war-time female staff, the “Kalamazoo Gals,” was responsible for that installation. (That fingerboard has since been replaced yet again).

March 31 F-5 Pegheads: Left F-5 75941, middle 76780, both with 1930s tuners installed by the factory. Right, 75950 with factory original tuners. Notice that in the repair on the left, the original peghead was redrilled; there are no drill holes visible on the peghead in the middle, yet it does have 1930s tuners. Also, notice that the string post on the original is mounted above the turning gear and that is reversed in the 1930s tuners.

As was the case with frets, Gibson did not repair worn tuners, but replaced them with current models. At some point in the 1930s, the tuners used by Gibson had a different configuration: the position of the tuner post and the round gear was reversed so that the string tension pulled the gears together instead of apart. Consequently, the new tuners would have to be mounted in a different position. To do this to a 1924 instrument, the old tuner post holes had to be plugged and new holes drilled to position the tuners on the peghead.

Comparison of tuners: Left to right, Gibson F5 75941 and 76780 with 19340s tuners and 75940 with 1924 models.

Since the peghead had to be redrilled to accommodate the replacement of tuners, it is our understanding that earlier versions of this repair would include a replacement of the peghead overlay to hide the work, as is the case on F-5 76780. How do we know this? In the photo below, compare the fern inlay on 76780 to the original from 1924 and to one from the mid-30s. It is definitely the later fern. This would not have been consistent with factory specification for peghead overlay in 1942, so that repair must have been earlier, in a time preceding current records. On the other hand, the peghead repair on 75941 could have been performed during the repair documented, as the tuners were consistent with factory specification and the original overlay was preserved: they simply plugged and redrilled and covered with finish, leaving the tell-tale marks of the process. (Note on tuners: All these original F-5 tuners were open back, and often suffered from build-up of dust, dirt, etc. If cleaned with a vibratory tumbler with fine walnut shells for 4-5 hours, they can often work as well as new [tip from Randy Wood; this works beautifully on any of the open back Waverly or Grover tuners made prior to World War II that have grown too stiff to turn]).

Left: Gibson F-5 76553 from March 31, 1924, showing Loar style fern inlay. Middle, 76780, March 31, 1924, with 1930s tuners and replaced peghead overlay; Right: 1934 F-5 94448 showing the redesigned inlay; notice the finer tendrils of the fern which is a match to the peghead of 76780. However since the type finish used in the repair of 76780 was discontinued around the same time that Gibson began to employ the new tuners, we deduce that this repair would most likely have performed earlier than the one listed in the 1942 document.

At this point, by far the majority of the Lloyd Loar F-5s have reached 100 years of age. There are still many more interesting mandolins and developments at Gibson to come throughout the rest of this year, but why not ramp up the celebration now? As the Gibson Lloyd Loar F-5 has played such an important role his career, we close with Tony Williamson leading an all-star cast with F-5 #75941 in a classic Charlie Parker composition, “Now’s The Time.” It’s a “Call To Jam,” so wherever you are, and whatever instrument you play, we invite you to get it out and and celebrate with us!