Kalamazoo Gazette, October 19, 1924, page 8. Similar articles appeared in a number of publications. (see below) Thanks to Roger Siminoff for pointing me to The Kalamazoo Gazette.

On October 17, 1924, Lloyd Loar signed an agreement with Gibson General Manager Guy Hart regarding the “final payment on all patent contracts and royalties.” (This document is reprinted in its entirety in Roger Siminoff’s “The Life and Work of Lloyd Allayre Loar” pp. 65 & 66.) Said payment of $550 was “to be absorbed…in instruments, accessories, tools and supplies.” In return, Loar agreed to assign to Gibson, Inc., all right to “patent, manufacture and sell … all instruments and instrument accessories” designed by him, or a design contributed to by him, during his time at Gibson. The document went on to specify a list of items concerned which included instrument models “F-5, H-5, K-5, L-5, UB, Tenor-Lute, Mastertone Banjo” and accessories such as tone-projector and resonator for Gibson banjos; adjustable bridge; narrow (snakehead) peghead; elevated pickguard; mutes, and “tone-tube, head and ball bearing ring” for banjos.

For better understanding of the October 17 agreement, we supplied a copy of the original agreement (kindly copied for us by Mr. Siminoff) to Mr. Trip Savery, President and COO of Curtis Media Group of Raleigh North Carolina. Mr. Savery reviewed the document, went over it with his contract attorney, and wrote this very considered response:

“I read this very simple document carefully. This is an agreement to give him (Lloyd Loar) monetary and final consideration for the patent contracts and royalties related to his work with Gibson from February 1920 until that date (October 17, 1924). This does not suggest that he is no longer an employee of Gibson. A separation and release agreement would be related to his employment, not any rights to patents although that could be incorporated into a release. The fact that it only references payments and obligations related to the patents, and not in his capacity as an employee, indicates that it is a separate and distinct agreement.

The_Brookfield Argus and the Linn County Farmer, October 28, 1924.

On October 18, a news release from Gibson announced Loar’s departure, and almost identical versions of this appeared in numerous newspaper publications that month. Based on our understanding of these documents, we observe that Gibson planned for Loar to “leave early in December” and that he “would continue his relationship with the concern…acting in an advisory capacity.” Although we have never seen an actual termination of employment agreement, we conclude that his departure was agreed upon on October 17, and that he would work for the next two months to facilitate the transition and coordinate the completion of his former projects and duties.

Signatures from the October 17 document, signifying the beginning of Lloyd Loar’s departure from Gibson. (courtesy Roger Siminoff; a copy of the same document was also supplied to us by Joe Spann)

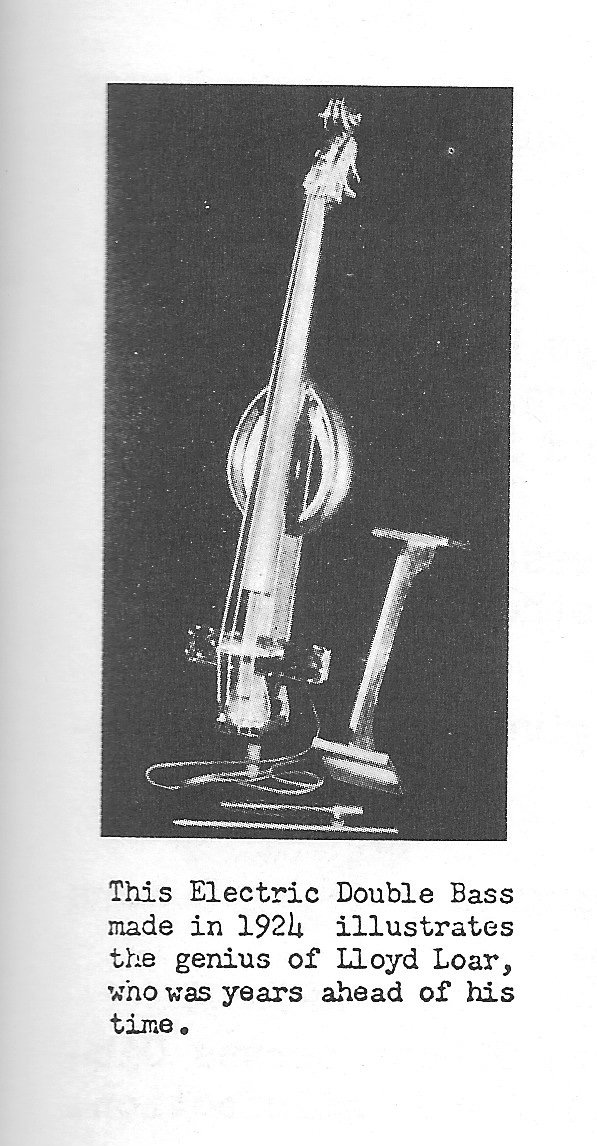

There is much controversy about exactly what Lloyd Loar contributed at Gibson from October through December. In Julius Bellson’s “The Gibson Story,” published in 1973, he indicates that Loar designed an “Electric Double Bass” which Gibson tried unsuccessfully to market to “teacher agents.” While we have documented that Loar’s colleague and friend Lewis Williams was building custom speakers by 1922 in his Kalamazoo business, “Specialty Radio,” it does seem possible that Williams and Loar may have at least discussed the possibility of electric instruments as early as 1924. However, there is no primary source document to confirm that any electric instruments were built until 1933 when Loar, Williams and Buttelman created the “Vivi-Tone Company.”

“The Gibson Story” by Julius Bellson, Chapter XV. While Bellson’s 1973 history of Gibson has been an invaluable source of information and reference for Gibson scholars since its inception, it is not without error. As Roger Siminoff points out in “The Life and Work of Lloyd Allayre Loar,” this instrument has a remarkable similarity to an instrument produced by Vivi-Tone.

We find irony in the fact that the first Gibson patent on an electric instrument was awarded to Guy Hart, who was neither musician, instrument designer nor electrical engineer. This may shed some insight on how patents of work by Gibson engineers were distributed among employees… or perhaps kept by management!

After signing the agreement of October 17, it seems unlikely that Lloyd Loar worked on any new designs during his remaining time at Gibson. Rather, his role may have been to oversee the issuance and promotion of the works that had been in progress for the last few years. In October 1924, The Master Model Tenor Lute, a model designed and stamped in 1923, was released, shipped, promoted… and, by 1925, discontinued.

1924 Gibson Tenor Lute #77282, perhaps the rarest model designed by Loar. (Photo Courtesy Lowell Levinger, Players Vintage Instruments). To the best of our knowledge, the tenor lute never made it into a Gibson catalog.

(Photo Courtesy Lowell Levinger, Players Vintage Instruments). The Tenor Lute was awarded Master Model Status, but did not receive a signature.

Music Trade Report, October 18, 1924. This news release issued by Gibson on October 14, 1924, confirms Lloyd Loar’s role in design and marketing.

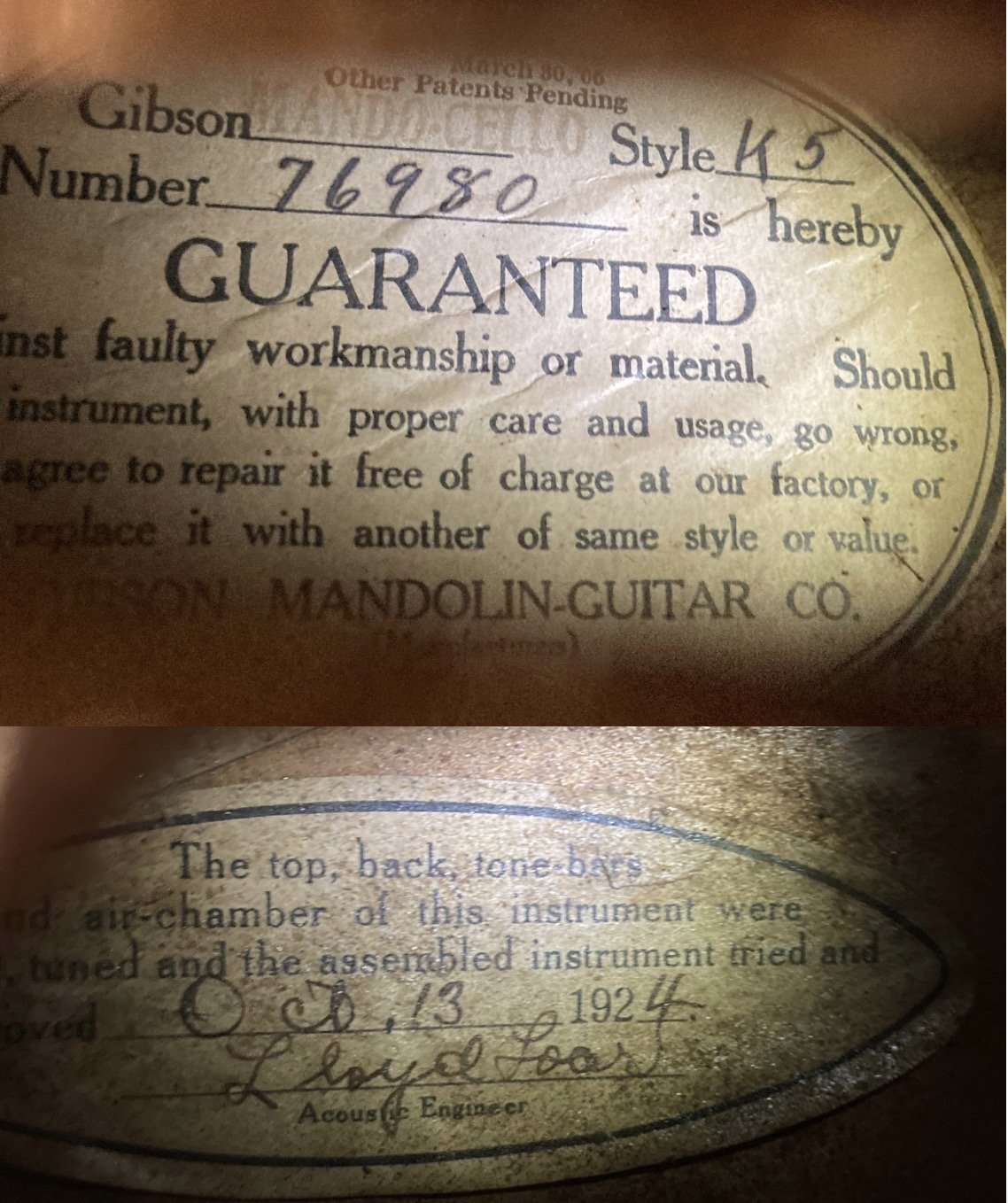

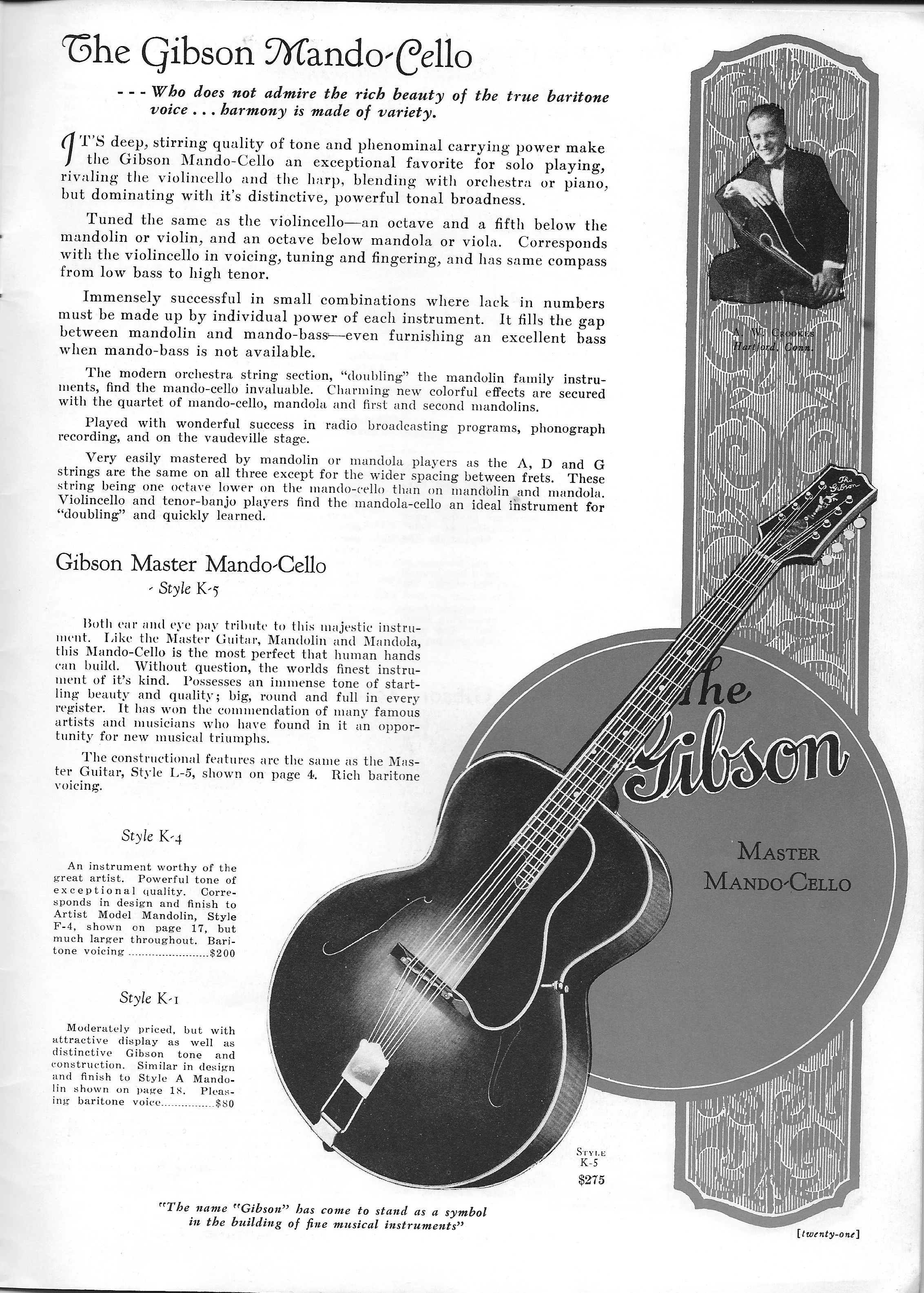

Other Master Model instruments known to have been released that month were six H-5 Mandolas and three K-5 Mandocellos. Both these models made their appearance in Gibson Catalog P, circa 1927. By then they were very scarce in production.

Gibson K-5 Mandocello dated October 13, 1924 (on left) and H-5 Mandola dated October 7, 1924.

Gibson Catalog Q, circa 1928, p. 20.

Gibson Catalog Q, circa 1928, p. 21.

Gibson K-5 Mandocello # 76981, dated October 13, 1924, which was sold to Conrad Gebelein for the ‘cello voice in his Baltimore Mandolin Orchestra, is the most famous and most played of that model. It is our understanding that it is still in use by that organization in that role to this day.

Baltimore Mandolin Orchestra, Gibson Catalog Q, 1928. Conrad Gebelein stands with baton on right; Gibson K-5 76981 is held by the lady in the center of the photo.

Gibson K-5 76981, (Photo courtesy Darryl Wolfe, The F-5 Journal)

Gibson K-5 76981, (Photo courtesy Darryl Wolfe, The F-5 Journal)

Also, in October of 1924, Gibson announced a new arrangement with Virzi Violins of New York City to produce instruments to be marketed and sold under the Gibson name. As Lloyd Loar had been such an advocate of the Virzi Brothers, it seems possible this might have been another arrangement that he helped negotiate.

Jacobs Orchestra Monthly And The Cadenza, October 1924.

Of course, Loar continued with his series of articles for Jacobs Orchestra Monthly And The Cadenza entitled “Acoustics For The Musician.” His theories on Overtones ran from pages 16 through 19 in the October issue. We find this article extremely interesting considering how this information may have influenced the development of the Master Model instruments.

Jacobs Orchestra Monthly And The Cadenza, pp. 16 & 17.

Jacobs Orchestra Monthly And The Cadenza, pp. 18 & 19.

While Lloyd Loar had been a frequent contributor to The Crescendo Magazines in previous years, the only mention of him in the last three months of 1924 (other than credits for musical arrangements) was a suggestion in the November issue by his friend and colleague William Place, Jr. that Loar be consulted—at Gibson, Inc.—on a matter of string instrument acoustics.

The Crescendo, November 1924, “Mandolinist’s Round Table,” by William Place, Jr. p. 20. A reply to a question from “V.A.H. of Portland Oregon” who asks “what is the proper scale length for a mandolin (distance from nut to bridge).”

Mrs. Shipp-Loar was staying with her mother at the time of the October 17th agreement and did not join her husband in Kalamazoo until the end of October. She continued her practice of traveling between her hometown in Brookfield, Missouri and Kalamazoo through December. It is by following her comings and goings that we were able to understand Lloyd Loar’s whereabouts in late 1924, and confirm that his departure from Kalamazoo to move to Boston did not take place until at least after Christmas of 1924 and more likely in early 1925.

On December 1, 2024, we plan to return with Episode 8: “Signing Off.” Stay tuned!