Signature label, Gibson F-5 76790. Photo courtesy Steve Gilchrist.

September 18, 1924: Lloyd Loar returned to the Master Model project for the first time since March 31, signing some of the best and last; on September 8, in an upset that shook the top echelon of Gibson, Inc., General Manager Harry Ferris stalked out the door. Accountant Guy Hart took over as GM and ramped up Ferris’ plan to dismiss “non-essential” personnel. This plan would include Lloyd Loar!

Gibson F-5 76790, one of three signed September 18, 1924. Photos courtesy Steve Gilchrist.

For the first time in almost 6 months, Master Model instruments, which had evidently been stamped in 1923, were once again being signed and dated. (For where Loar was during that lapse of time, see the previous “Episode 5: A Tale Of Two Cities.”) The F-5s, H-5s and K-5s dated from September 13 to December 1 of 1924 would be the last, and in our opinion, among the best to be signed by acoustic engineer, Lloyd Loar.

Three of these were F-5s dated September 18, 1924. Curiously, the serial numbers of these mandolins fit into or immediately after the sequence of those signed on March 31, 1924. Other Gibson mandolin models issued in September had serial numbers at least two hundred units higher. The appointments on all three of the September F-5s were virtually identical to the numerically adjacent F-5s from March. Those appointments which differ from most Loar F-5s made prior to March of 1924 include fern inlay in peghead; white body binding; extremely dark finish, factory installed Virzi Tone Producer and red velour lining in the Geib and Schaefer case.

Gibson F-5 #76553, dated March 31, 1924. Appointments are almost identical to those of F-5 76790, dated September 13, 1924.

As an interesting footnote, September 18, 1924 F-5 76790 was sold by Walter Kaye Bauer in 1932. (Bauer had also acquired a very similar mandolin, F-5 76779, for his student and teaching assistant Ada Merrifield in 1927). Among the items found in the case of 76790 was a letter from Bauer dated January 21, 1932 on “The Crescendo” letterhead, as by then, Bauer had inherited editorship from Walter O’Dell. This mandolin has recently received a brilliant restoration by Australian luthier Steve Gilchrist, and a detailed account of that work, and a copy of the Bauer letter can be found on Mr. Gilchrist’s website.

Gibson F-5 76790 in original case with letter from Walter Kaye Bauer. Photo courtesy Steve Gilchrist.

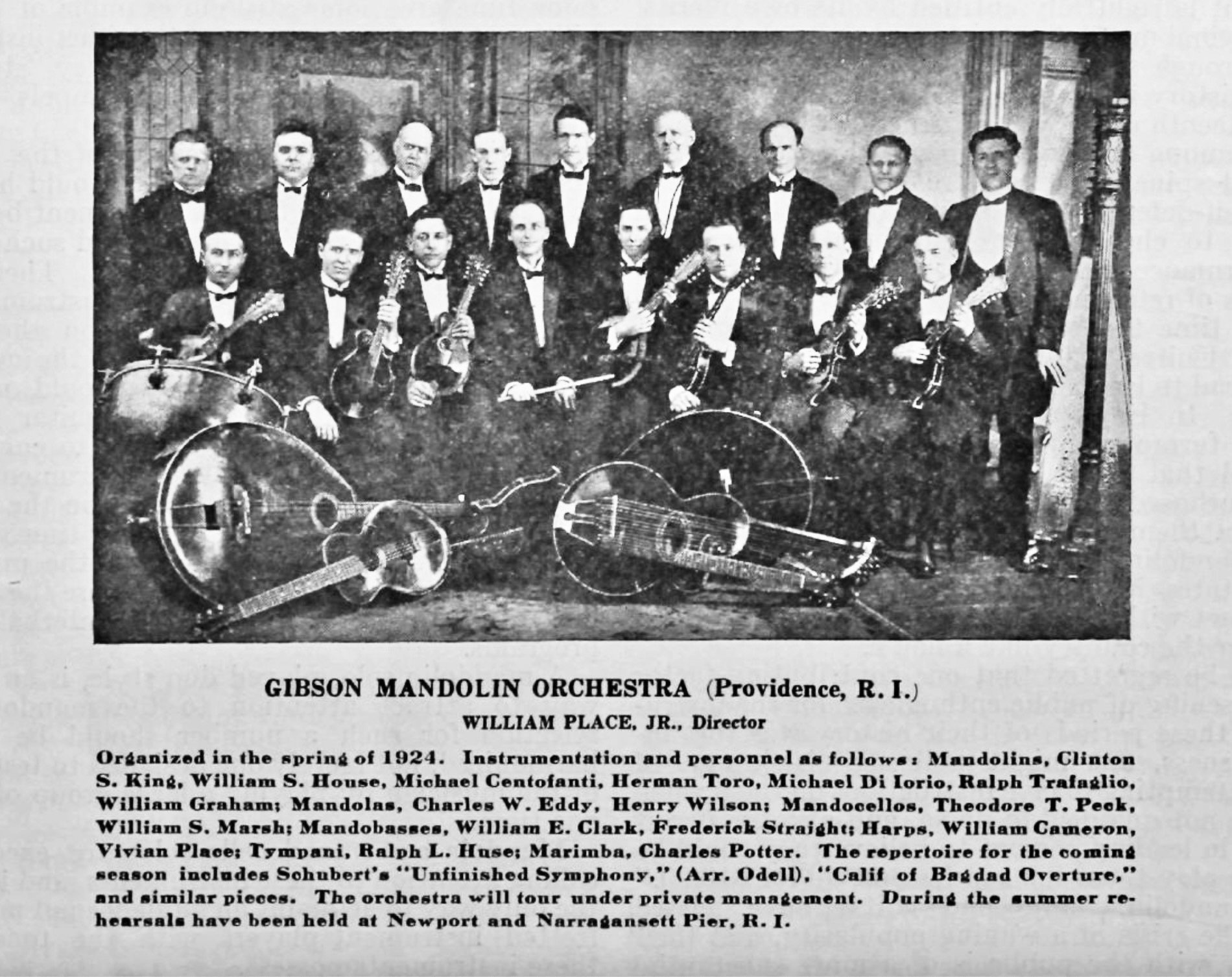

By the autumn of 1924, many Master Model instruments were appearing in mandolin orchestras in the United States and Canada. While many scholars point out a log-jam of Gibson F-5s at the factory and in music shops across the country caused by over-production and slow sales, photographic evidence shows a healthy interest in the unique sound.

Cover of the September 1924 Crescendo magazine with Herman F. Toro (seated, second fro left) holding his March 31, 1924 F-5.

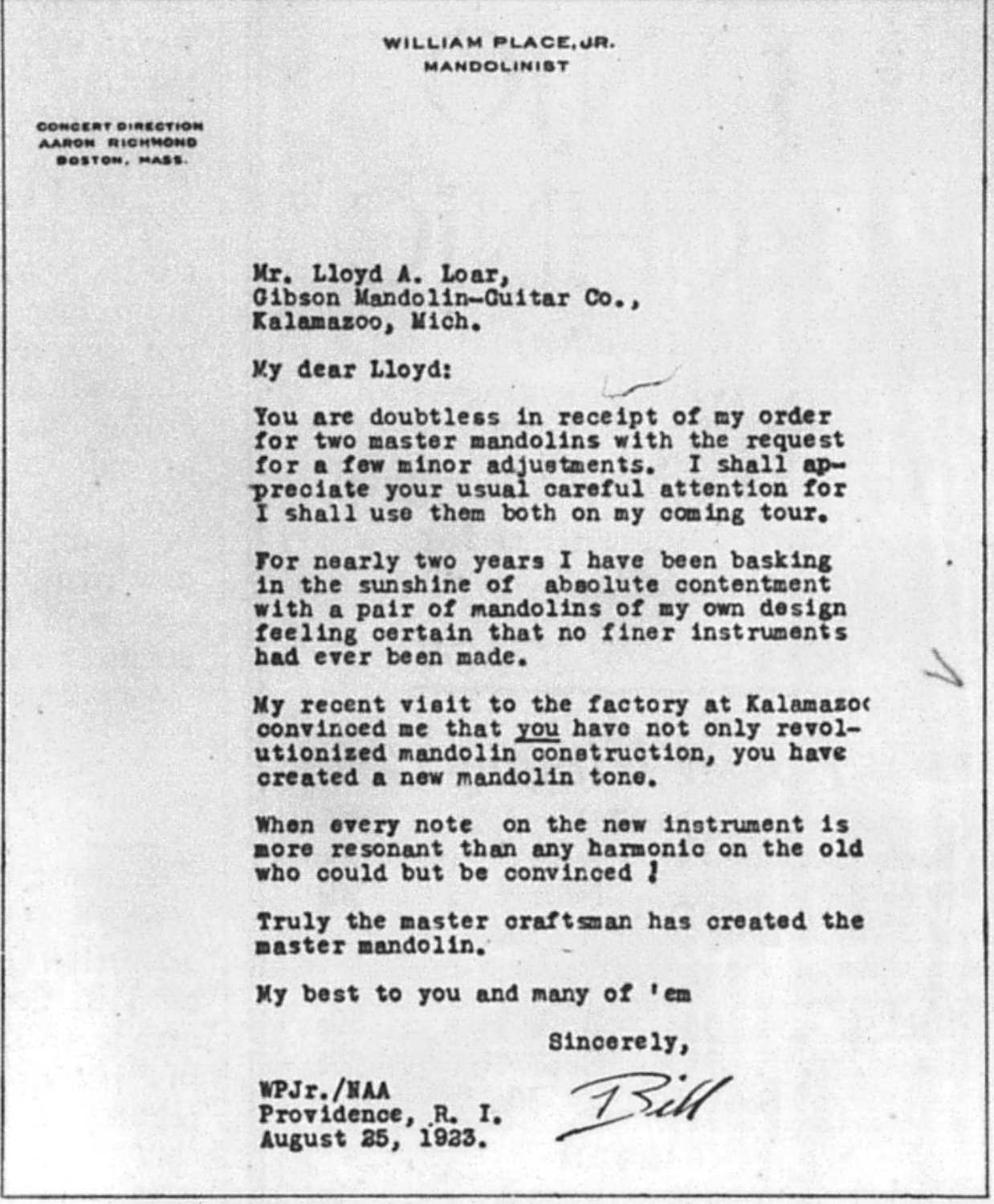

The March 31, 1924 mandolins were appearing in photos as early as September. For example, it seems reasonable to suspect that the F-5 that appears in this version of the Providence Orchestra is the “Toro,” #75940. After William Place acquired F-5 #73676 (June 13, 1923) during a visited with Loar at the Gibson factory in Kalamazoo on August of 1923, he ordered two more F-5s for the Providence Orchestra, with a request “for a few minor adjustments.”

The Cadenza, October, 1923. Was the Toro F5 was one of those ordered in August of '23?

Despite the musical success of the Master Model program, the problems that confronted Gibson, Inc., were financial.

Music Trade Report, September 22, 1924.

General Manager Harry Ferris of Gibson, Inc., exploded into the annual meeting of The Board Of Directors on Monday morning, September 8, 1924, blaming President John W. Adams and other members of the board for the financial problems the company had been facing. In short, Ferris was livid that The Board had continued to pay dividends to shareholders (i.e., themselves) while the company was operating at a loss.

Was Mr. Ferris’ presentation an astounding act of bravado or the cry of a man awash in frustration? Evidently that frustration began when he took over the position at the head of Gibson in October of 1923. In his book “Spann’s Guide To Gibson,” author Joe Spann describes Mr. Ferris’ complaint (Mr. Spann kindly provided this author with a copy of his source, a document by Ferris dated September 2, 1924). Walter Carter delves more deeply into the woes of Ferris’ brief tenure at Gibson in his book “Gibson Guitars: 100 Years Of An American Icon.” When Ferris took the job at Gibson, in his first report of November 23, 1923, he requested additional capital to carry the company through 1924. He blamed the financial disaster he had inherited on mismanagement during “the years 1916 to 1920.” On February 18, 1924, Ferris issued a document implementing many changes including reducing the number of models; trimming down the work force and firing “non-essential personnel;” selling to music stores instead of artists/teachers; and stopping all payments of dividends to stockholders. Ferris even changed the name of the Gibson Mandolin and Guitar Company to Gibson, Inc., removing the association with “outdated instruments like mandolins and guitars.” While he felt the banjo was the future of the company, he described the Gibson banjo as “having the worst reputation of any banjo on the market.” To document the finances of the company, Ferris hired Guy Hart as auditor.

In his report to the Board of Directors on September 2, Ferris pointed out that during his year at Gibson, the company had shown a profit, but it was too little too late. The mismanagement of the company prior to his arrival left no choice but to turn over all the directors’ stock “to Kalamazoo City Savings Bank, Herbert N. Parker, trustee” and that the bank be given directorial power over Gibson, Inc. While Ferris took credit for the profit shown in 1923 (he failed to mention that the entire country was experiencing a strong recovery from recession), he blamed the board itself for the losses of previous years which left Gibson still in the red. It seems that Ferris had already made Mr. Parker privy to the company’s problems. President Adams, who was also the Kalamazoo Circuit Court Judge, was not used to being addressed in such a manner. When Ferris handed over a typewritten letter assigning his resignation for January 1, 1925, Adams asked for his resignation to take effect immediately. Ferris scratched a note in ink on a scrap of paper and dated his resignation September 8, 1924. Then, Adams turned to the accountant Guy Hart and promoted him General Manager of Gibson, Inc.

Guy Hart was born September 13, 1888 in Henshaw, Kentucky (northwest Kentucky near the Illinois border) to Geary and Mary Hart. According to the 1900 Census, the Hart family moved across the river to Carrier Mills, Illinois and 11-year old Guy is listed as a student. By 1910, the family moved further west to Poplar Bluff Missouri, where Hart, who evidently had a head for numbers, worked as a bookkeeper in the office for Poplar Bluff Lumber and Manufacturing Co. Later, Hart landed a job as a traveling salesman with Hartwell Brothers Woodworks at 17th and Hanover, Chicago Heights, Chicago, Illinois. By 1917, he was working out their sales office in Denver, Colorado. After a brief stint in the military beginning in December, 1918, he rejoined Hartwell Brothers in their Chicago office. It is unclear exactly how he came to the attention of Ferris, but with his background in sales and bookkeeping, he was an obvious choice.

Unlike Lewis Williams, Hart was neither affable nor well-loved; unlike Lloyd Loar, he was neither brilliant nor respected. In contrast to Ferris, he had a quiet manner which appealed to the Board of Directors. Moreover, he was determined to do whatever it took to increase profits. He was willing to make quick and harsh judgements, especially when he saw a benefit in firing an employee.

In many ways, Hart used Ferris’ report of February 18, 1923 as a blueprint for managing the company. He reduced the number of models in production and focused on just those that he thought would sell, including the banjo. Remember, according to Ferris, Gibson banjos had the “worst reputation of any banjo on the market.” While the Loar-designed trapdoor Gibson TB series had a unique and rather pleasant sound, banjo players across the country were switching to William Lange’s new Paramounts which were advertised as “The Greatest Banjos Ever Produced.” With their heavy metal tone rings, flanges and resonators, they gave the jazz players the volume and projection they needed to be heard among the brass instruments. Even long-time Gibson endorsers like orchestra leaders Paul Whiteman and Isham Jones switched to Paramounts.

Left: Paul Whiteman Orchestra with Paramount banjo (Crescendo, August 1922); Right, Music Trades, May 17, 1924.

Left: Advertisement in Music Trades January 6, 1924; Right, 1924 Paramount style D with flange and resonator.

Compared to Gibson advertisements for the “Gibsonian banjo,” there is little wonder that Paramount was out-selling Gibson in that market.

Gibsonian Banjo The Commercial Appeal, Memphis, Tennessee, April 6, 1924 · P 47

The Muscatine Journal, Muscatine, Iowa, September 16, 1924, Page 11.

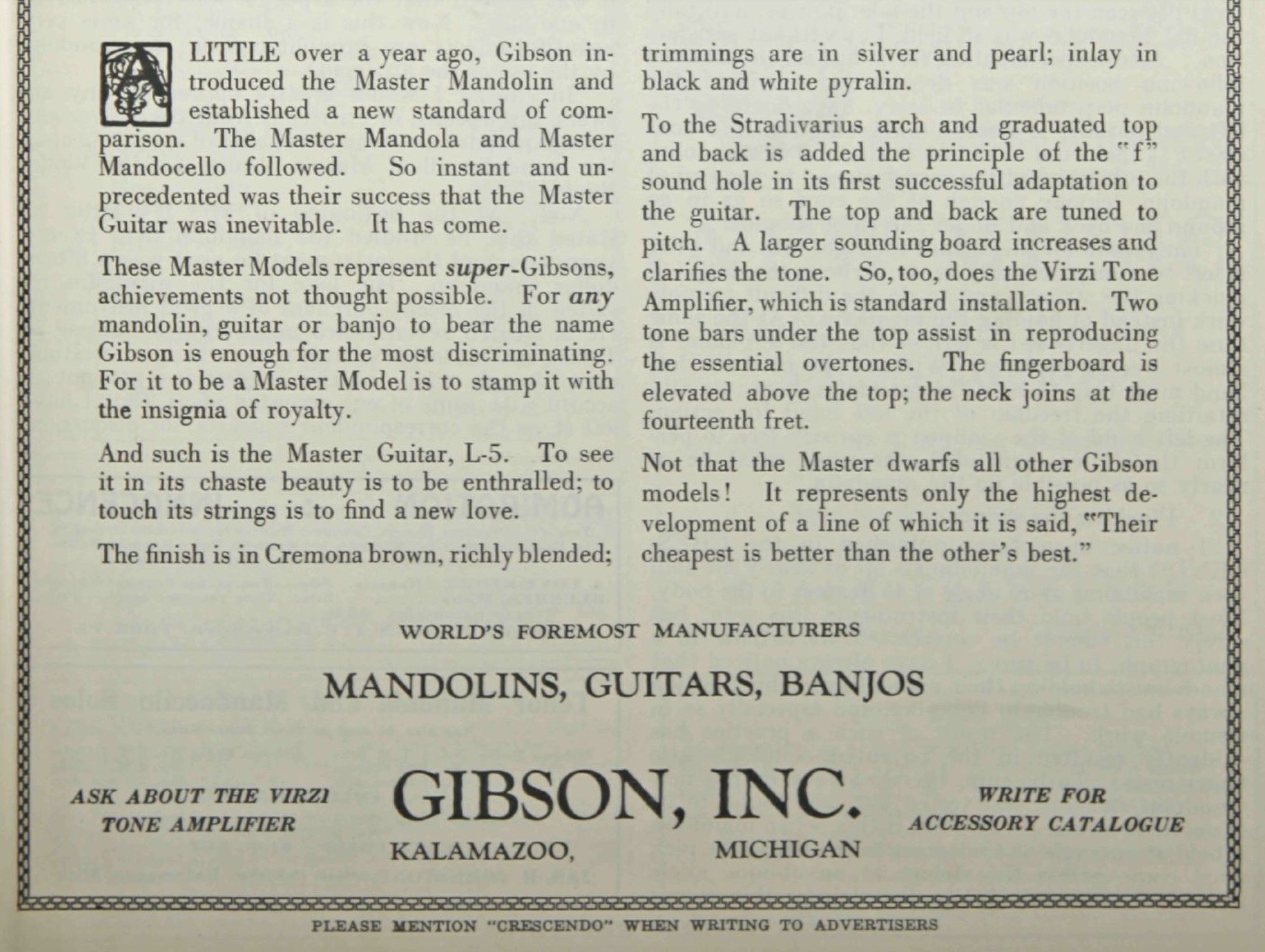

While Gibson clearly needed to develop a new banjo line to become competitive, a flagship instrument was needed sooner rather than later. It was most likely Sales Manager Frank Campbell that moved the L-5 guitar to front and center, replacing the F-5 mandolin in Gibson advertisements. At some point, Hart came to understand that the guitar would be the foundation of the Gibson Company in years to come. It was an uncanny prediction, and the kind of sales savvy that kept Hart at the helm of Gibson for the next 24 years.

The Crescendo, September, 1924, p. 19.

While change was erupting at the head of Gibson, Lloyd Loar was back in his acoustic laboratory in Kalamazoo completing his assignments there. During September, Mrs. Shipp Loar stayed with her mother in Brookfield, Missouri, and performed locally without her husband.

The Daily Argus, Brookfield, Missouri, September 3, 1924 · P. 1

As a writer, Lloyd Loar had contributed to “The Crescendo,” “The Cadenza,” and “Music Trades” magazines, submitting articles from his residence in Kalamazoo, Michigan. During this time, many of his writings supported and endorsed the innovations he had brought to Gibson. Since the inaugural edition of “Jacob’s Orchestra Monthly And The Cadenza” in April, Loar had authored prominently placed articles with an appeal to a more general musical audience. In the September issue, he began his most ambition writing project to date, a sixteen part series entitled “Acoustics For The Musician.” These extraordinary articles provide a master class in music as a natural phenomenon and how musical instruments work.

"Jacobs Orchestra Monthly And The Cadenza" September, 1924, p. 4.

Coming In October! “Episode 7: The Beginning Of The End.” Stay tuned.